The edges of the earth in Greek and Roman thought

Return to Chapter 1

Adapted from an article by Jona Lendering

World map of Hecataeus

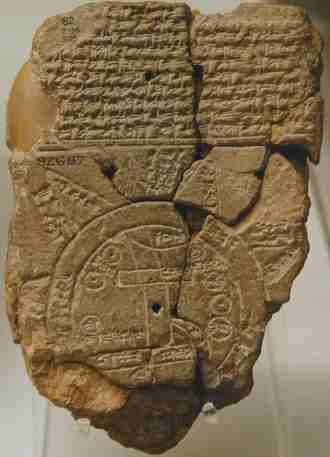

The Babylonian map of the world. British Museum, London The UK

Schematic Greek world map. Design Jona Lendering

The Etemenanki of Babylon

The most famous ziggurat is the "tower of Babel" mentioned in the Bible: a description of the Etemenanki of Babylon. According to the Babylonian creation epic Enûma êliš the god Marduk defended the other gods against the diabolical monster Tiamat. After he had killed it, he brought order to the cosmos, built the Esagila sanctuary, which was the center of the new world, and created mankind.

The Etemenanki was next to the Esagila, and this means that the temple tower was erected at the center of the world, as the axis of the universe. Here, a straight line connected earth and heaven. This aspect of Babylonian cosmology is echoed in the Biblical story, where the builders say "let us build a tower whose top may reach unto heaven".

Without exception, they believed that their own country was the the center of a disk-like world. A Mesopotamian world map shows a circular earth, surrounded by an Ocean with islands full of wonders. Babylon was thought of as the center of the universe, its ziggurat, the famous Etemenanki, being the 'foundation of heaven on earth'. (It is still known as the 'tower of Babel' of Genesis 11.) The Egyptians, Phoenicians, Hittites and Jews all had comparable ideas about the shape of the world: they all lived in the center of the earth, and they all believed that the edges of the world's disk were inhabited by strange animals.

For example, the author of the Epic of Gilgameš situated the monster Humbaba in the far west, and the author of the biblical book Jonah believed that the prophet fled to the far west, where he was devoured by a giant sea creature.

The Greeks shared this belief. The demigod Heracles went to the edges of the earth to meet the legendary Amazons, the Hesperides and the monster Geryon. Of course, Greece was the center of the world, and the Greeks believed that they could prove it. Once, in the mythological past, the supreme god Zeus had released two eagles at the edges of the earth, and they had met each other at Delphi.

A monument was erected to celebrate the outcome of this mytho-scientific experiment: it was called the omphalos ('navel'). Probably, the story was invented to give significance to a very ancient monument, the meaning of which was no longer understood. In fact, it is likely that the Delphian omphalos originally was a baitylos, a 'house of god' that is well-known from the ancient Near East. The black stone of Mecca is the most famous example, but the Phrygian mother goddess Cybele and the sun god Elagabal of Emesa were venerated in a similar fashion.

The Greeks developed another idea: the distinction between civilized people and barbarians. Originally, barbaros simply meant 'babbler' and was used to indicate everybody who did not speak Greek. After the Greek victory in the Persian wars (492-479), the word became pejorative: a barbarian was not only unable to speak Greek, but was inferior as well. At that moment, the two ideas had already been combined: the center of the world was inhabited by civilized Greeks, the periphery by barbarians.

Until the late sixth century BCE, the Greeks conceptualized the world as a series of concentric circles. Greece was surrounded by the Mediterranean Sea (with large islands like Sicily, Italy, and Cyprus; the Mediterranean was surrounded by the three continents, and behind the continents was the Ocean, which surrounded the world disk. Here, one could encounter strange monsters: Homer's Odyssey mentions a great variety of them. The edges of the continents were inhabited by savage, monstrous barbarians, the opposites of the civilized Greeks in the middle of the earth.

Of course the Greeks knew that this was too schematic, and after c.500 BCE, they started to understand better what the world looked like. Especially after Alexander's conquest of the Achaemenid empire (334-323) and the voyage of Pytheas of Massilia (c.325), the world maps of the Greeks became a lot more reliable. Nevertheless, notions about the barbarians on the edges of the earth were always present when the Greeks (and later: the Romans) described the world.

Herodotus and Strabo

The map of Hecataeus of Miletus (c.550-c.490) can be seen as the first attempt to break away from the schematic approach described above. It is more or less correct as far as the Mediterranean is depicted, but Asia is much too small. Moreover, Hecataeus still considered the earth to be a flat dish with clearly defined edges.

The same can be said about the Greek researcher Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c.480-c.429), although he had a far better understanding of the shape of the world and may be called the father of geography. But although he criticized Hecataeus for "showing the Ocean running round a perfectly circular globe", Herodotus made similar mistakes. He accepted a clear distinction between the civilized Greeks in the center of the earth and the barbarians on the world's edges.

In his view, those savages did everything the other way round. The same can be said for other things. Whereas Greece is poor in minerals, "it would seem to be a fact that the remotest parts of the world are the richest in minerals and produce the finest specimens of both animal and vegetable life"

Of course, there were regions between the civilized world of the Greeks and the reversed world at the edges of the earth. This can be illustrated with the following example.

West of the seaport at the mouth of the Borysthenes (Dnieper) which lies in the middle of the Scythian coastline - the first people are the Graeco-Scythian tribe called Callipidae, and their neighbors to the eastward are the Alizones. Both these peoples resemble the Scythians in their way of life, and also grow grain for food, as well as onions, leeks, lentils, and millet.

North of the Alizones are agricultural Scythian tribes, growing grain not for food but for export.

Beyond these are the Neuri, and north of the Neuri the country, so far as we know, is uninhabited. [...]

Beyond [the uninhabited country] live the Maneaters - who have no connexion with the Scythians but are a quite distinct race. [Herodotus, Histories 4.17-18; tr. Aubrey de Sélincourt.

Here we can see clearly that, according to Herodotus, the world becomes stranger and stranger when one travels away from Greece, until one has reached the ends of the earth, where humans behave inhumanely.

Many Greek authors speculated about the people on the edges of the terrestrial disk. For example, Ctesias of Cnidus describes in his History of India people with dog's heads (cynoscephalae), people with one big foot, righteous Pygmies ('fist-men'), and the Martichora, a kind of tiger with a human face and three rows of teeth. In other texts, we encounter people with goat's legs, dwarfs, baldheads, yellow people, black people, werewolves, nudists. Some of these did really exist, others were the result of reversal, still others had their origins in the fantasy of the nation that also invented centaurs, gorgons, and cyclopes.

In the first century BCE, the geographer Strabo of Amasia developed a complete "inversion theory" about the barbarians on the edges of the world, which can be described as follows. In the first place, civilized people -Strabo means: Greeks and Romans- live along rivers and on coastal plains. As a corollary, barbarians live in forests and mountainous regions. (The logical consequence is that the shores of the Ocean resemble fjords.) This geographical difference results in different modes of production. The country of the barbarians is poor and allows only animal husbandry; but on the fertile soils of civilized countries, arable farming is possible. Opposed to civilized, bread-eating people, stand nomadic barbarians, who live on a diet of meat and dairy.

The consequence is a different way of life. Greeks and Romans can live in towns (the Macedonian philosopher Aristotle of Stagira had once defined "man" as "an animal living in cities") and feel no need to carry weapons, because they are living in peace with their neighbors. They can use their spare time to relax and study. Barbarians, on the other hand, never remain on the same place for a long time. Together with their sheep and cows, they roam through the mountains. They have to be on their guard, because there are always cattle thieves; therefore, they are permanently under arms.

Strabo's civilized city-dwellers can live according to law and ethics, but the barbarians have neither law nor good customs. One of the most popular stereotypes in ancient literature is that barbarians do not respect the divine laws of hospitality, and eat their guests or serve them to their gods (cf. Herodotus' Maneaters above).

Obviously, good taste is confined to the cities surrounding the Mediterranean sea. There, people with nice hair cuts wear fine clothes, e.g. Greek chitons or Roman togas. On the edges of the earth, people have mustaches and are dressed -if they are dressed at all!- in trousers, the ultimate example of indecency.

According to Strabo, the barbarians are trapped in a vicious circle. Because they live in the wilderness, arable farming is impossible, and they are forced to live as poachers and marauders. If someone has the idea to start a farm, his hostile neighbors will force him to give it up. Under these circumstances, there is no room for civilization, and therefore, the barbarian is socially handicapped. He withdraws from anybody's company, and prefers to live in the wilderness.

So, there is no escape from his situation. Time and again, the barbarians are forced to fight. Therefore, they are fierce people, aggressive and virile. These savages lack any moral scruples: when they have concluded a treaty, they will ignore it as soon as they see an opportunity to pillage their neighbor's country. Because they are always fighting, they do not think. They prefer force to reason, have a simple way of behaving, and believe only in honor and courage.

Because barbarians never think, they can easily be manipulated. They love any enterprise that gives them an opportunity to show their courage. In general terms, they love change. They never stay on the same place, easily accept other leaders, ignore treaties, and do not know what marital fidelity is.

This is Strabo's theory of barbarism and civilization. Of course, they are extreme types: most people lived somewhere between absolute barbarism and absolute civilization. Besides, most Greek or Roman authors conceded that some barbarians were in fact noble savages (e.g., Spartacus and Julius Civilis, the leader of the Batavian revolt), and almost every writer warned for the dangers of civilization: decadence and effeminacy.

However, the stereotypical barbarian on the edges of the earth was always present in the minds of Greek and Roman authors. Everybody knew that in the remotest areas lived the most dangerous warriors.

The first author to describe the Low Countries was Pytheas of Massilia, who passed along the coast of Flanders and Holland in his way to the amber island Helgoland in c.325 BCE. He noted that in these regions, more people died in the struggle against water than in the struggle against men. After all, the edge of the world was constantly attacked by the sea. Four centuries later, the Roman author Pliny the Elder expressed the same sentiment.

There, twice in every twenty-four hours, the ocean's vast tide sweeps in a flood over a large stretch of land and hides Nature's everlasting controversy about whether this region belongs to the land or to the sea.

There these wretched peoples occupy high ground, or manmade platforms constructed above the level of the highest tide they experience; they live in huts built on the site so chosen and are like sailors in ships when the waters cover the surrounding land, but when the tide has receded they are like shipwrecked victims. Around their huts they catch fish as they try to escape with the ebbing tide. It does not fall to their lot to keep herds and live on milk, like neighboring tribes, nor even to fight with wild animals, since all undergrowth has been pushed far back. [Pliny the Elder, Natural history 16.2-3; tr. John Healy]

Even worse, when you approached the edge of the world, parts of the land spontaneously start to float:

The shores are occupied by oaks which have a vigorous growth rate, and these trees, when undermined by the waves or driven by blasts of wind, carry away vast islands of soil trapped in their roots. Thus balanced, the oak-trees float in an upright position, with the result that our fleets gave often been terrified by the 'wide rigging' of their huge branches when they have been driven by the waves -almost deliberately it would seem- against the bows of ships riding at anchor for the night; consequently, our ships have had no option but to fight a naval battle against trees! [Pliny the Elder, Natural history 16.5 tr. John Healy]

These two texts happen to be pretty accurate, but no doubt, Pliny's readers were amazed by the wonders of this odd country. One century earlier, Julius Caesar had manipulated their preconceptions when he described the war against king Ambiorix of the Eburones. This barbarian tribe belonged to the Belgians, a group of tribes that were, according to Caesar the toughest of all Gauls. They are farthest away from the culture and civilized ways of the Roman province, and merchants, bringing those things that tend to make men soft, very seldom reach them; moreover, they are close to the Germans across the Rhine and are continuously at war with them. [Caesar, Gallic war 1.1.2; tr. Anne and Peter Wiseman]

The implication is that beyond the Belgians, between the Rhine and the Ocean, lived the Germans, who were even less civilized and more dangerous than the Belgians. As one could expect from a barbarian, Ambiorix had not been loyal to the Romans, even though he had concluded a treaty. Instead, he had unexpectedly attacked and destroyed a legion. However, Caesar retaliated by exterminating his tribe.

Some of his people fled into the forest of the Ardennes, others into the continuous belt of marshes. Those who lived nearest to the sea hid in islands that are cut off from the mainland by the high tide. [Caesar, Gallic war 6.31.1; tr. Anne and Peter Wiseman]

Every reader will have felt admiration for Caesar, who fought against those savage warriors on the edges of the earth, who lived in forests and marshes. However, those islands "that are cut off from the mainland by the high tide" are fictitious: Ambiorix lived in the neighborhood of modern Tongeren and Maastricht, and the only islands that fit the description are the Frisian islands, which are 300 kilometers away. (The Zeeland archipelago did not exist in Antiquity.)

We have already seen that the Greeks and Romans believed that the edge of the world consisted of forests and mountains. Indeed, we find several authors maintaining that the Dutch coast is rocky (e.g., Tacitus, Annals 2.24). Forests are also mentioned, especially in religious contexts. For example, during the Batavian revolt, the leader of the rebels, Julius Civilis, invited the nobles and the most enterprising commoners to a sacred grove, ostensibly for a banquet. When he saw that darkness and merriment had inflamed their hearts, he addressed them. [Tacitus, Histories 4.14; tr. Kenneth Wellesley]

This is a remarkable line, and many Dutch scholars have been looking where this sacred grove might have been. In fact, their question is wrong. To a Roman author like Tacitus, mentioning a forest was something like adding couleur locale to a story about barbarians. In his Germania, the same writer describes the hunting customs of the Germanic tribes, ignoring the fact that many Germans were farmers.

Tacitus often uses the two extreme types of barbarism and civilization. In his description of the Batavian revolt in the Histories, Julius Civilis is a noble savage, who opposes a decadent and incapable Roman commander, Marcus Hordeonius Flaccus. In his Annals, Tacitus tells about two Frisians who visited Rome, and caused quite a stir with their uncivilized behavior (Annals 13.54).

Other authors use the same stereotypes to describe the Low Countries. Strabo of Amasia and other writers inform their readers that the Romans recruited their cavalry among the tribes living near the Ocean, "because they are by nature most aggressive" (Geography 4.4.2).

When Cassius Dio describes the battle in the Teutoburg Forest (September 9 CE), he mentions mountains, ravines, and impenetrable forests. The battlefield has been discovered near Osnabrück, and there were neither mountains nor ravines. There may have been a forest, but it was certainly not impenetrable, because there was a village on walking distance from the excavated part of the battlefield.

In the first century CE, the last remains of tribal society disappeared from Gallia Belgica, and the area along the Rhine (called Germania Inferior) followed a bit later, after the Batavian revolt of 69-70. There were Roman cities like Tongeren, Cologne, Xanten and Nijmegen, and the most important economic activity was agriculture. Nevertheless, Greek and Roman texts continue to describe the Low Countries as if its inhabitants are ferocious savages.

This attitude towards the Low Countries (and any other country on the edges of the earth) can easily be explained. Any literate Greek or Roman was taught at school that he was civilized, and learned what civilization truly meant. Another reason is that he studied "classical" authors, and no newer texts. When the historian Arrian of Nicomedia (second century CE) wrote a treatise on far-away India, he used sources from the fourth century BCE, because later texts were written in what he regarded as lousy Greek.

As a consequence of these two factors, the ideas about barbarians on the edges of the earth remained intact until the fourth and fifth century CE. We can still find the stereotypes in the Orations of Libanius (59.132), in Sidonius Apollinaris' Panegyric on Majorian (238-250) and in the theological treatises of Salvian (On God's government 7.63-64). In fact, they have survived until the present day, because many scholars still use these texts instead of the results of archeaeology to study the ancient Low Countries.

Literature

Klaus Karttunen, "The Ethnography of the Fringes" in: Egbert Bakker, Irene de Jong and Hans van Wees (eds.), Brill's Companion to Herodotus (2002 Leiden), pages 457-474

Jona Lendering, De randen van de aarde. De Romeinen tussen Schelde en Eems (2000 Amsterdam) 9-18

Wilfried Nippel, Griechen, Barbaren und "Wilde". Alte Geschichte und Sozialanthropologie (1990 Frankfurt am Main) 11-29

Patrick Thollard, Barbarie et civilisation chez Strabon. Étude critique des Livres III et IV de la Geographie (1987 Paris)

Return to Chapter 1