Rhoecus By James Russel Lowell

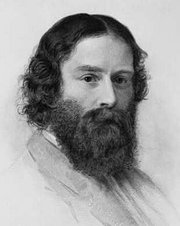

James Russell Lowell (22 February 1819 – 12 August 1891) was a United States Romantic poet, critic, satirist, writer, diplomat, and abolitionist. Lowell was born, lived most of his life, and died, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was the son of Charles Lowell (1782-1861).

He was brought up near open countryside, and always felt close to nature; he also became acquainted with the work of Edmund Spenser and Sir Walter Scott in childhood, and was taught old ballads by his mother.

He graduated from Harvard University in 1838, after an undistinguished academic career. During his college course he wrote a number of trivial pieces for a college magazine, and shortly after graduating printed for private circulation the poem his class had asked him to write for their graduation festivities.

While studying law he contributed poems and prose articles to various magazines.

After an unhappy love affair, he became engaged to Maria White and the next twelve years of his life were deeply affected by her influence.

Lowell was already regarded as a man of wit and poetic sentiment; Miss White was admired for her beauty, her character and her intellectual gifts, and the two became the hero and heroine of their social circle.

In 1841, Lowell published A Year's Life, which was dedicated to his future wife, and recorded his new emotions with a backward glance at the preceding period of depression and irresolution. Lowell was inspired to new efforts towards self-support, and though nominally maintaining his law office, he joined a friend, Robert Carter, in founding a literary journal, The Pioneer. It opened the way to new ideals in literature and art, and the writers to whom Lowell turned for assistance--Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Whittier, Edgar Allan Poe, Story and Parsons, none of them yet possessed of a wide reputation--indicate the acumen of the editor.

In 1843 he published a collection of his poems, and a year later he gathered up certain material which he had printed, edited and added to it, and produced Conversations on Some of the Old Poets.

In the spring of 1845 the Lowells returned to Cambridge and made their home at Elmwood. On the last day of the year their first child, Blanche, was born, but she lived only fifteen months. A second daughter, Mabel, was born six months after Blanche's death, and lived to survive her father; a third, Rose, died in infancy.

He contributed poems to the daily press, prompted by the slavery question; early in 1846, he was a correspondent of the London Daily News, and in the spring of 1848 he formed a connection with the National Anti-Slavery Standard of New York, agreeing to contribute weekly either a poem or a prose article.

The prose articles form a series of incisive, witty and sometimes prophetic diatribes. It was a period of great mental activity, and four books which stand as witnesses to the Lowell of 1848, namely, the second series of Poems, containing among others

"Columbus,"

"An Indian Summer Reverie,"

"To the Dandelion,";

"The Changeling";

A Fable for Critics, in which, after the manner of Leigh Hunt's The Feast of the Poets, he characterizes in witty verse and with good-natured satire American contemporary writers. The Vision of Sir Launfal, a romantic story suggested by the Arthurian legends--one of his most popular poems; and finally The Biglow Papers.

A YOUTH named Rhoecus, wandering in the wood,

Saw an old oak, just trembling to its fall,

And, feeling pity of so fair a tree,

He propped its gray trunk with admiring care,

And with a thoughtless footstep loitered on.

But, as he turned, he heard a voice behind

That murmured, "Rhoecus!" 'T was as if the leaves,

Stirred by a passing breath, had murmured it,

And, while he paused bewildered, yet again

It murmured "Rhoecus!" softer than a breeze.

He started and beheld with dizzy eyes

What seemed the substance of a happy dream

Stand there before him, spreading a warm glow

Within the green glooms of the shadowy oak.

It seemed a woman's shape, yet all too fair

To be a woman, and with eyes too meek

For any that were wont to mate with gods.

All naked like a goddess stood she there,

And like a goddess all too beautiful

To feel the earth-born guiltiness of shame.

"Rhoecus, I am the Dryad of this tree,"

Thus she began, dropping her low-toned words

Serene, and full, and clear, as drops of dew,

"And with it I am doomed to live and die;

The rain and sunshine are my caterers,

Nor have I other bliss than simple life;

Now ask me what thou wilt, that I can give,

And with a thankful joy it shall be thine."

Then Rhoecus, with a flutter at the heart,

Yet, by the prompting of such beauty, bold,

Answered: "What is there that can satisfy

The endless craving of the soul but love?

Give me thy love, or but the hope of that

Which must be evermore my spirit's goal."

After a little pause she said again,

But with a glimpse of sadness in her tone,

"I give it, Rhoecus, though a perilous gift;

An hour before the sunset meet me here."

And straightway there was nothing he could see

But the green glooms beneath the shadowy oak,

And not a sound came to his straining ears

But the low trickling rustle of the leaves,

And far away upon an emerald slope

The falter of an idle shepherd's pipe.

. . . . .

Young Rhoecus had a faithful heart enough,

But one that in the present dwelt too much,

And, taking with blithe welcome whatsoe'er

Chance gave of joy, was wholly bound in that,

Like the contented peasant of a vale,

Deemed it the world, and never looked beyond.

So, haply meeting in the afternoon

Some comrades who were playing at dice,

He joined them, and forgot all else beside.

The dice were rattling at the merriest,

And Rhoecus, who had met but sorry luck,

Just laughed in triumph at a happy throw,

When through the room hummed a yellow bee

That buzzed around his ear with down-dropped legs

As if to light. And Rhoecus laughed and said,

Feeling how red and flushed he was with loss,

"By Venus! does he take me for a rose?"

And brushed him off with rough,, impatient hand.

But still the bee came back, and thrice again

Rhoecus did beat him off with growing wrath.

Then through the window flew the wounded bee,

And Rhoecus, tracking him with angry eyes

Saw a sharp mountain-peak of Thessaly

Against the red disk of the setting sun,--

And instantly the blood sank from his heart,

As if its very walls had caved away.

Without a word he turnd, and, rushing forth,

Ran madly through the city and the gate,

And o'er the plain, which was now the wood's long shade,

By the low sun thrown forward broad and dim,

Darkened wellnigh unto the city's wall.

Quite spent and out of breath he reached the tree,

And, listening fearfully, he heard once more

The low voice murmur, "Rhoecus!" close at hand:

Whereat he looked around him, but could see

Naught but the deepening glooms beneath the oak.

Then sighed the voice, "O Rhoecus! nevermore

Shalt thou behold me or by day or night,

Me, who would fain have blessed thee with a love

More ripe and bounteous than ever yet

Filled up with nectar any mortal heart;

But thou didst scorn my humble messenger,

And sent'st him back to me with bruiséd wings.

We spirits only show to gentle eyes,

We ever ask an undivided love.

And he who scorns the least of Nature's works

Is thencefoth shut out and exiled from all.

Farewell! for thou canst never see me more."

James Russel Lowell