Œnone by Alfred Lord Tennyson

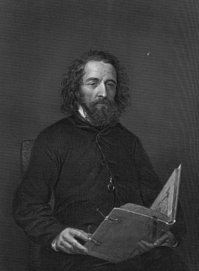

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.The Lord Tennyson

British poet Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (August 6, 1809 – October 6, 1892) was one of the most popular English poets of his time.

Much of his verse was based on classical or mythological themes.

Early Life

Tennyson was born in Lincolnshire, a rector's son and one of twelve children. His father had fallen out with his family and been disinherited; he drank heavily and became mentally unstable. Tennyson and two of his elder brothers were writing poetry in their teens, and a collection of poems by all three was published locally when Alfred was only seventeen.

One of those brothers, Charles Tennyson Turner, later married Louisa Sellwood, younger sister of Alfred's future wife; the other poet brother was Frederick Tennyson.

Education and First Publication

Tennyson attended Louth grammar school and entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1828, where he joined the secret society called the Cambridge Apostles. At Cambridge Tennyson met Arthur Henry Hallam, who became his best friend.

He published his first solo collection of poems, "Poems Chiefly Lyrical" in 1830. "Claribel" and "Mariana", which later took their place among Tennyson's most celebrated poems, were included in this volume.

In 1833, Tennyson published his second book of poetry, which included his best-known poem, The Lady of Shalott. The volume was met with heavy criticism, which so discouraged Tennyson that he did not publish again for ten more years, although he continued to write.

1833 also struck another heavy blow to Tennyson: his friend Hallam was stricken with influenza and died in September of that year.

Tennyson and his family were allowed to stay in the rectory for some time, but later moved to Essex. An unwise investment in an ecclesiastical wood-carving enterprise resulted in the loss of much of their money, and this may have been one of the reasons why Tennyson was so late in marrying.

It was in 1850 that Tennyson reached the pinnacle of his career, being appointed Poet Laureate in succession to William Wordsworth and in the same year producing his masterpiece, In Memoriam A.H.H., dedicated to Arthur Hallam. In the same year, Tennyson himself married Emily Sellwood, whom he had known since childhood, at the village of Shiplake. They had two sons, Hallam -- named after his late friend -- and Lionel.

The Poet Laureate

He held the position of Poet Laureate from 1850 until his death, turning out appropriate but mediocre verse, such as a poem of greeting to Alexandra of Denmark when she arrived in Britain to marry the future King Edward VII. In 1855, Tennyson produced one of his best known works, "The Charge of the Light Brigade," a dramatic tribute to the British cavalry men involved in an ill-advised charge on 25 October 1854 during the Crimean War.

Other works written as Laureate include Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington and Ode Sung at the Opening of the International Exhibition.

Queen Victoria was an ardent admirer of Tennyson's work, and in 1884 created him Baron Tennyson, of Aldworth in the County of Sussex and of Freshwater in the Isle of Wight. He was the first English writer raised to the Peerage.

Tennyson continued writing into his eighties, and died on October 6, 1892.

Lord Tennyson's death was widely mourned, and he was buried at Westminster Abbey. He was succeeded as 2nd Baron Tennyson by his son, Hallam, who produced an authorised biography of his father in 1897, and was later the second Governor-General of Australia.

There lies a vale in Ida, lovelier

Than all the valleys of Ionian hills.

The swimming vapour slopes athwart the glen,

Puts forth an arm, and creeps from pine to pine,

And loiters, slowly drawn. On either hand

The lawns and meadow-ledges midway down

Hang rich in flowers, and far below them roars

The long brook falling thro' the clov'n ravine

In cataract after cataract to the sea.

Behind the valley topmost Gargarus

Stands up and takes the morning: but in front

The gorges, opening wide apart, reveal

Troas and Ilion's column'd citadel,

The crown of Troas. Hither came at noon

Mournful Œnone, wandering forlorn

Of Paris, once her playmate on the hills.

Her cheek had lost the rose, and round her neck

Floated her hair or seem'd to float in rest.

She, leaning on a fragment twined with vine,

Sang to the stillness, till the mountain-shade

Sloped downward to her seat from the upper cliff.

"O mother Ida, many-fountain'd Ida,

Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

For now the noonday quiet holds the hill:

The grasshopper is silent in the grass:

The lizard, with his shadow on the stone,

Rests like a shadow, and the winds are dead.

The purple flower droops: the golden bee

Is lily-cradled: I alone awake.

My eyes are full of tears, my heart of love,

My heart is breaking, and my eyes are dim,

And I am all aweary of my life.

"O mother Ida, many-fountain'd Ida,

Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

Hear me, O Earth, hear me, O Hills, O Caves

That house the cold crown'd snake! O mountain brooks,

I am the daughter of a River-God,

Hear me, for I will speak, and build up all

My sorrow with my song, as yonder walls

Rose slowly to a music slowly breathed,

A cloud that gather'd shape: for it may be

That, while I speak of it, a little while

My heart may wander from its deeper woe.

"O mother Ida, many-fountain'd Ida,

Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

I waited underneath the dawning hills,

Aloft the mountain lawn was dewy-dark,

And dewy-dark aloft the mountain pine:

Beautiful Paris, evil-hearted Paris,

Leading a jet-black goat white-horn'd, white-hooved,

Came up from reedy Simois all alone.

"O mother Ida, harken ere I die.

Far-off the torrent call'd me from the cleft:

Far up the solitary morning smote

The streaks of virgin snow. With down-dropt eyes

I sat alone: white-breasted like a star

Fronting the dawn he moved; a leopard skin

Droop'd from his shoulder, but his sunny hair

Cluster'd about his temples like a God's:

And his cheek brighten'd as the foam-bow brightens

When the wind blows the foam, and all my heart

Went forth to embrace him coming ere he came.

"Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

He smiled, and opening out his milk-white palm

Disclosed a fruit of pure Hesperian gold,

That smelt ambrosially, and while I look'd

And listen'd, the full-flowing river of speech

Came down upon my heart. `My own Œnone,

Beautiful-brow'd Œnone, my own soul,

Behold this fruit, whose gleaming rind ingrav'n

"For the most fair," would seem to award it thine,

As lovelier than whatever Oread haunt

The knolls of Ida, loveliest in all grace

Of movement, and the charm of married brows.'

"Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

He prest the blossom of his lips to mine,

And added 'This was cast upon the board,

When all the full-faced presence of the Gods

Ranged in the halls of Peleus; whereupon

Rose feud, with question unto whom 'twere due:

But light-foot Iris brought it yester-eve,

Delivering that to me, by common voice

Elected umpire, Herè comes to-day,

Pallas and Aphroditè, claiming each

This meed of fairest. Thou, within the cave

Behind yon whispering tuft of oldest pine,

Mayst well behold them unbeheld, unheard

Hear all, and see thy Paris judge of Gods.'

"Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

It was the deep midnoon: one silvery cloud

Had lost his way between the piney sides

Of this long glen. Then to the bower they came,

Naked they came to that smooth-swarded bower,

And at their feet the crocus brake like fire,

Violet, amaracus, and asphodel,

Lotos and lilies: and a wind arose,

And overhead the wandering ivy and vine,

This way and that, in many a wild festoon

Ran riot, garlanding the gnarled boughs

With bunch and berry and flower thro' and thro'.

"O mother Ida, harken ere I die.

On the tree-tops a crested peacock lit,

And o'er him flow'd a golden cloud, and lean'd

Upon him, slowly dropping fragrant dew.

Then first I heard the voice of her, to whom

Coming thro' Heaven, like a light that grows

Larger and clearer, with one mind the Gods

Rise up for reverence. She to Paris made

Proffer of royal power, ample rule

Unquestion'd, overflowing revenue

Wherewith to embellish state, 'from many a vale

And river-sunder'd champaign clothed with corn,

Or labour'd mine undrainable of ore.

Honour,' she said, 'and homage, tax and toll,

From many an inland town and haven large,

Mast-throng'd beneath her shadowing citadel

In glassy bays among her tallest towers.'

"O mother Ida, harken ere I die.

Still she spake on and still she spake of power,

'Which in all action is the end of all;

Power fitted to the season; wisdom-bred

And throned of wisdom--from all neighbour crowns

Alliance and allegiance, till thy hand

Fail from the sceptre-staff. Such boon from me,

From me, Heaven's Queen, Paris, to thee king-born,

A shepherd all thy life but yet king-born,

Should come most welcome, seeing men, in power

Only, are likest Gods, who have attain'd

Rest in a happy place and quiet seats

Above the thunder, with undying bliss

In knowledge of their own supremacy.'

"Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

She ceased, and Paris held the costly fruit

Out at arm's-length, so much the thought of power

Flatter'd his spirit; but Pallas where she stood

Somewhat apart, her clear and bared limbs

O'erthwarted with the brazen-headed spear

Upon her pearly shoulder leaning cold,

The while, above, her full and earnest eye

Over her snow-cold breast and angry cheek

Kept watch, waiting decision, made reply.

"`Self-reverence, self-knowledge, self-control,

These three alone lead life to sovereign power.

Yet not for power (power of herself

Would come uncall'd for) but to live by law,

Acting the law we live by without fear;

And, because right is right, to follow right

Were wisdom in the scorn of consequence.'

"Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

Again she said: 'I woo thee not with gifts.

Sequel of guerdon could not alter me

To fairer. Judge thou me by what I am,

So shalt thou find me fairest. Yet, indeed,

If gazing on divinity disrobed

Thy mortal eyes are frail to judge of fair,

Unbias'd by self-profit, oh! rest thee sure

That I shall love thee well and cleave to thee,

So that my vigour, wedded to thy blood,

Shall strike within thy pulses, like a God's,

To push thee forward thro' a life of shocks,

Dangers, and deeds, until endurance grow

Sinew'd with action, and the full-grown will,

Circled thro' all experiences, pure law,

Commeasure perfect freedom.' Here she ceas'd

And Paris ponder'd, and I cried, 'O Paris,

Give it to Pallas!' but he heard me not,

Or hearing would not hear me, woe is me!

"O mother Ida, many-fountain'd Ida,

Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

Italian Aphroditè beautiful,

Fresh as the foam, new-bathed in Paphian wells,

With rosy slender fingers backward drew

From her warm brows and bosom her deep hair

Ambrosial, golden round her lucid throat

And shoulder: from the violets her light foot

Shone rosy-white, and o'er her rounded form

Between the shadows of the vine-bunches

Floated the glowing sunlights, as she moved.

"Dear mother Ida, harken ere I die.

She with a subtle smile in her mild eyes,

The herald of her triumph, drawing nigh

Half-whisper'd in his ear, 'I promise thee

The fairest and most loving wife in Greece.'

She spoke and laugh'd: I shut my sight for fear:

But when I look'd, Paris had raised his arm,

And I beheld great Herè's angry eyes,

As she withdrew into the golden cloud,

And I was left alone within the bower;

And from that time to this I am alone,

And I shall be alone until I die.

"Yet, mother Ida, harken ere I die.

Fairest--why fairest wife? am I not fair?

My love hath told me so a thousand times.

Methinks I must be fair, for yesterday,

When I past by, a wild and wanton pard,

Eyed like the evening star, with playful tail

Crouch'd fawning in the weed. Most loving is she?

Ah me, my mountain shepherd, that my arms

Were wound about thee, and my hot lips prest

Close, close to thine in that quick-falling dew

Of fruitful kisses, thick as Autumn rains

Flash in the pools of whirling Simois!

"O mother, hear me yet before I die.

They came, they cut away my tallest pines,

My tall dark pines, that plumed the craggy ledge

High over the blue gorge, and all between

The snowy peak and snow-white cataract

Foster'd the callow eaglet--from beneath

Whose thick mysterious boughs in the dark morn

The panther's roar came muffled, while I sat

Low in the valley. Never, never more

Shall lone Œnone see the morning mist

Sweep thro' them; never see them overlaid

With narrow moon-lit slips of silver cloud,

Between the loud stream and the trembling stars.

"O mother, hear me yet before I die.

I wish that somewhere in the ruin'd folds,

Among the fragments tumbled from the glens,

Or the dry thickets, I could meet with her

The Abominable, that uninvited came

Into the fair Pele{:i}an banquet-hall,

And cast the golden fruit upon the board,

And bred this change; that I might speak my mind,

And tell her to her face how much I hate

Her presence, hated both of Gods and men.

"O mother, hear me yet before I die.

Hath he not sworn his love a thousand times,

In this green valley, under this green hill,

Ev'n on this hand, and sitting on this stone?

Seal'd it with kisses? water'd it with tears?

O happy tears, and how unlike to these!

O happy Heaven, how canst thou see my face?

O happy earth, how canst thou bear my weight?

O death, death, death, thou ever-floating cloud,

There are enough unhappy on this earth,

Pass by the happy souls, that love to live:

I pray thee, pass before my light of life,

And shadow all my soul, that I may die.

Thou weighest heavy on the heart within,

Weigh heavy on my eyelids: let me die.

"O mother, hear me yet before I die.

I will not die alone, for fiery thoughts

Do shape themselves within me, more and more,

Whereof I catch the issue, as I hear

Dead sounds at night come from the inmost hills,

Like footsteps upon wool. I dimly see

My far-off doubtful purpose, as a mother

Conjectures of the features of her child

Ere it is born: her child!--a shudder comes

Across me: never child be born of me,

Unblest, to vex me with his father's eyes!

"O mother, hear me yet before I die.

Hear me, O earth. I will not die alone,

Lest their shrill happy laughter come to me

Walking the cold and starless road of death

Uncomforted, leaving my ancient love

With the Greek woman. I will rise and go

Down into Troy, and ere the stars come forth

Talk with the wild Cassandra, for she says

A fire dances before her, and a sound

Rings ever in her ears of armed men.

What this may be I know not, but I know

That, wheresoe'er I am by night and day,

All earth and air seem only burning fire."