|

|

This Project Gutenberg EBook was produced by Ted Garvin, Taavi Kalju, and the Online Distributed Proofreaders Europe at http://dp.rastko.net

FIANS, FAIRIES AND PICTS

BY

DAVID MacRITCHIE

AUTHOR OF

"THE TESTIMONY OF TRADITION"

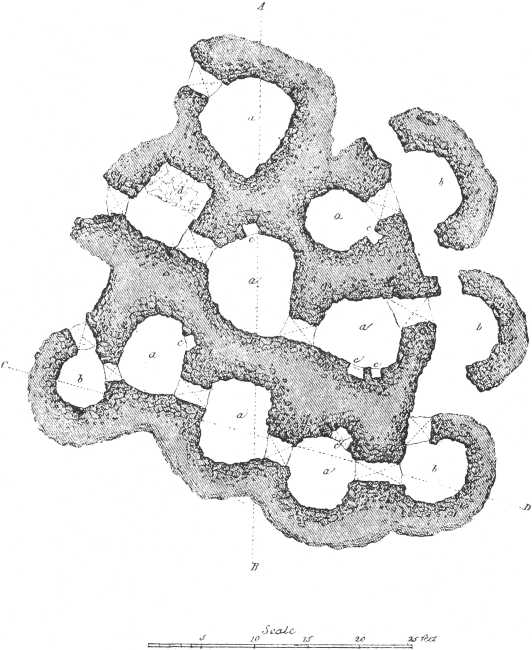

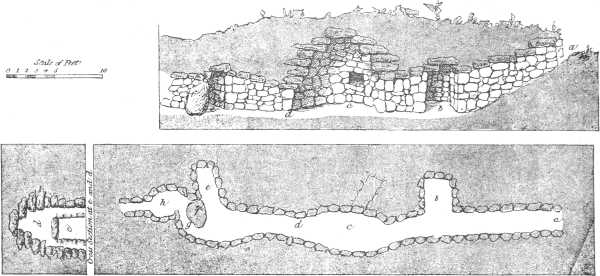

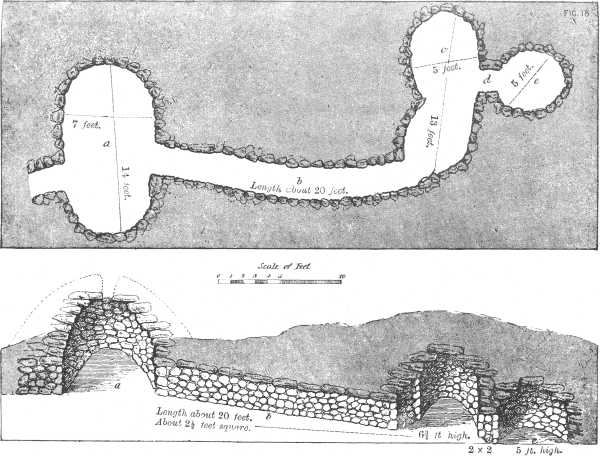

PLATE I.

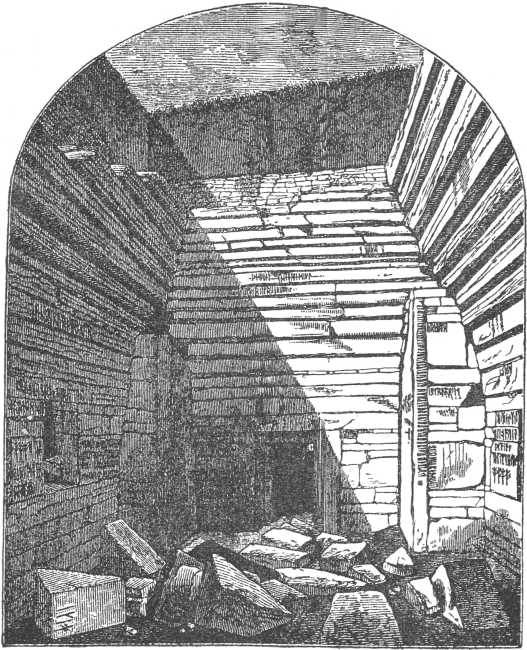

SELECTIONAL VIEW AND GROUND PLAN OF UNDERGROUND GALLERY, CALLED UAMH SGALABHAD, NEAR MOL A DEAS, HUISHNISH, ISLAND OF SOUTH UIST.

Frontispiece.

"Sometimes ... it seems that the stones are really speaking—speaking of the old things, of the time when the strange fishes and animals lived that are turned into stone now, and the lakes were here; and then of the time when the little Bushmen lived here, so small and so ugly, and used to sleep in the wild dog holes, and in the 'sloots,' and eat snakes, and shoot the bucks with their poisoned arrows ... Now the Boers have shot them all, so that we never see a little yellow face peeping out among the stones ... And the wild bucks have gone, and those days, and we are here."—Waldo, in The Story of an African Farm.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRÜBNER & CO., LTD.

PATERNOSTER HOUSE, CHARING CROSS ROAD

1893

INTRODUCTION.

The following treatise is to some extent a re-statement and partly an amplification of a theory I have elsewhere advanced.[1] But as that theory, although it has been advocated by several writers, especially during the past half-century, is not familiar to everybody, some remarks of an explanatory nature are necessary. And if this explanation assumes a narrative form, not without a tinge of autobiography, it is because this seems the most convenient way of stating the case.

It is now a dozen years or thereabouts since I first read the "Popular Tales of the West Highlands," by Mr. J.F. Campbell, otherwise known by his courtesy-title of "Campbell of Islay." Mr. Campbell was, as many people know, a Highland gentleman of good family, who devoted much of his time to collecting and studying the oral traditions of his own district and of many lands. His equipment as a student of West Highland folklore was unique. He had the necessary[Pg vi] knowledge of Gaelic, the hereditary connection with the district which made him at home with the poorest peasant, and the sympathetic nature which proved a master-key in opening the storehouse of inherited belief. It is not likely that another Campbell of Islay will arise, and, indeed, in these days of decaying tradition, he would be born too late.

In reading his book, then, for the first time, what impressed me more than anything else in his pages were statements such as the following:—

"The ancient Gauls wore helmets which represented beasts. The enchanted king's sons, when they come home to their dwellings, put off cochal [a Gaelic word signifying], the husk, and become men; and when they go out they resume the cochal, and become animals of various kinds. May this not mean that they put on their armour? They marry a plurality of wives in many stories. In short, the enchanted warriors are, as I verily believe, nothing but real men, and their manners real manners, seen through a haze of centuries.... I do not mean that the tales date from any particular period, but that traces of all periods may be found in them—that various actors have played the same parts time out of mind, and that their manners and customs are all mixed together, and truly, though confusedly, represented—that giants and fairies and enchanted princes were men ... that tales are but garbled popular history, of a long journey through forests and wilds, inhabited by savages and wild beasts; of events that occurred on the way from east to west, in the year of grace, once upon a time" (I. cxv.-cxvi.). "The[Pg vii] Highland giants were not so big but that their conquerors wore their clothes; they were not so strong that men could not beat them, even by wrestling. They were not quite savages; for though some lived in caves, others had houses and cattle and hoards of spoil" (I. xcix.). "And though I do not myself believe that fairies are ... I believe there once was a small race of people in these islands, who are remembered as fairies, for the fairy belief is not confined to the Highlanders of Scotland" (I. c.) "This class of stories is so widely spread, so matter-of-fact, hangs so well together, and is so implicitly believed all over the United Kingdom, that I am persuaded of the former existence of a race of men in these islands who were smaller in stature than the Celts; who used stone arrows, lived in conical mounds like the Lapps, knew some mechanical arts, pilfered goods and stole children; and were perhaps contemporary with some species of wild cattle and horses and great auks, which frequented marshy ground, and are now remembered as water-bulls and water-horses, and boobries, and such like impossible creatures" (IV. 344).

And much more to the same effect,[2] with which it is unnecessary to trouble the reader. Now, all this was quite new to me. If I had ever given a second thought to the so-called "supernatural" beings of tradition, it was only to dismiss them, in the conventional manner as creatures of the imagination. But these ideas of Mr. Campbell's were decidedly interest[Pg viii]ing, and deserving of consideration. It was obvious that tradition, especially where there had been an intermixture of races, could not preserve one clear, unblemished record of the past; and this he fully recognised. But it seemed equally obvious that the "matter-of-fact" element to which he refers could not have owed its origin to myth or fancy. The question being fascinating, there was therefore no alternative but to make further inquiry. And the more it was considered, the more did his theory proclaim its reasonableness. He suggests, for example, that certain "fairy herds" in Sutherlandshire were probably reindeer, that the "fairies" who milked those reindeer were probably of the same race as Lapps, and that not unlikely they were the people historically known as Picts. The fact that Picts once occupied northern Scotland formed no obstacle to his theory. And when I learned that the reindeer was hunted in that part of Scotland as recently as the twelfth century, that remains of reindeer horns are still to be found in the counties of Sutherland, Ross, and Caithness, sometimes in the very structures ascribed to the Picts, then I perceived this to be a theory which, to quote his words, "hung well together." Further, the actual Lapps are a small-statured race, the fairies also were so described, and this, too, I found to be the traditional idea regarding the Picts. Here the identification was closer still.[Pg ix] Then came the consideration: The fairies lived in hollow hillocks and under the ground: what kind of dwellings are the Picts supposed to have occupied? The answer to this question still further strengthened Mr. Campbell's conjecture. There yet exist numerous underground structures and artificial mounds whose interior shows them to have been dwelling-places; and these are in some places known as "fairy halls" and in others as "Picts' houses." (Illustrations of these are shown in the present volume, and are specially referred to in the annexed paper.)

The examination, therefore, of this interesting theory not only helped greatly to bear out its probable correctness, but it further began to appear that by following this method of inquiry new lights might be thrown upon history—perhaps upon very remote history. It was clear that the question was not a simple one. All tradition is obscured by the darkness of time, and genuine fact is mixed up with ideas which belong to the world of religion and of myth. Even in Mr. Campbell's own statements there were seeming contradictions. These, however, it is not my present purpose to discuss; since they do not vitally affect his main contention.

The Lapp-Dwarf parallel was gone into very fully by Professor Nilsson in his Primitive Inhabitants of Scandinavia, written twenty years before the "West[Pg x] Highland Tales." Not that he, either, was the originator of that theory, for it is frequently referred to by Sir Walter Scott, who accepted it himself.[3] "In fact," he says, "there seems reason to conclude that these duergar [in English, dwarfs] were originally nothing else than the diminutive natives of the Lappish, Lettish and Finnish nations, who, flying before the conquering weapons of the Asae, sought the most retired regions of the north, and there endeavoured to hide themselves from their eastern invaders." Scott, again, refers us back to Einar Gudmund, an Icelandic writer of the second half of the sixteenth century, whom I would cite as the earliest "Euhemerus" of northern lands, were it not for the fact that he is obviously much more than a theorist, and is beyond all doubt speaking of an actual race, as may be seen from an incident which he relates.

But, although the popular memory may retain for many centuries the impress of historical facts, these become inevitably blurred and modified by the lapse of time and the ignorance of the very people who preserve the tradition. As an illustration of this, I may cite the instance of the dwarfs of Yesso, referred to in the following pages. These people still survived[Pg xi] as a separate community until the first half of the seventeenth century, if not later. They occupied semi-subterranean or "pit" dwellings, and are said to have been under four feet in height. But, although the modern inhabitants of that island still describe them, on the whole, in these terms, a new belief regarding them has recently sprouted up in one corner. The Aïno word signifying "pit-dweller" is also not unlike the word for a burdock leaf. It was known that those dwarfs were little people. Obviously, then, their name must have meant "people living under burdock leaves" (instead of "in pits"). And so, to some of the modern natives of Yesso, those historical dwarfs of the seventeenth century "were so small that if caught in a shower of rain or attacked by an enemy, they would stand beneath a burdock leaf for shelter, or flee thither to hide."[4]

In that instance, we see before our eyes the whole process by which a real race has been transformed into an unreal impossibility, within a period of two centuries or so. Had the extinction (or modification by inter-marriage or by the processes of evolution) of those[Pg xii] Yesso dwarfs taken place a thousand years earlier, the difficulty of identifying them would have been greatly increased. After a race has once disappeared from sight, the popular terms describing it must become more vague and confused with every century. Thus, in a certain traditional Scotch story there is mention of a number of "little black creatures with spades." The description is delightfully comprehensive. It would be quite applicable to a gang of Andaman coolies. On the other hand, if we exclude the "spades," it might be applied to any "little black creatures"—say a colony of tadpoles or of black-beetles. So that, when a poet or an artist gets hold of a tradition which has reached this stage of uncertainty, he may give the reins to his fancy, so long as he portrays some kind—any kind—of "little black creatures."[5]

Before parting altogether from the Yesso dwarfs, notice may be taken of a folk-tale containing an[Pg xiii] incident which obviously derives its existence from them, or from a branch of their race. In Mr. Andrew Lang's "Green Fairy Book" there is introduced a certain Chinese "Story of Hok Lee and the Dwarfs." It appears to be also current in Japan, to judge from a reviewer's remark, that "the clever artist who has illustrated the book must have known the Japanese story, for he gets some of his ideas from the Japanese picture-maker." In the story of Hok Lee the dwarfs are represented as living in subterranean dwellings, and in the picture they are portrayed as half-naked, with (for the most part) shaggy beards and eyebrows, and bald heads. It is wonderfully near the truth. The baldness is one of the most striking characteristics of those actual dwarfs, and is caused by a certain skin-disease, induced by their dirty habits, from which a great number of them suffer, or did suffer. The shaggy beards and eyebrows are equally characteristic of the race; and their custom of occupying half-underground dwellings has given them the name by which they are remembered in Japan at the present day. The exact scene of the story is a matter of minor importance. Those people appear to have been known to the Chinese for at least twelve centuries, and to the Japanese for a much longer period. Thus, it was quite unnecessary for any novelist in China or Japan to invent such people, since they already existed. As for[Pg xiv] the details of that particular story, or of any other of the kind, it is not to be supposed that a belief in its historical basis necessarily implies an acceptance of every statement contained in it. On this principle, one would be bound to accept the truth of every "snake-story," for the simple reason that one believed in the existence of snakes. Still, it is possible, and perhaps not improbable, that tales which preserve the memory of those people, may also be fairly accurate in many of the statements made regarding them. The reason, however, of introducing this particular story is to show that the Chinese or Japanese romancer did not require to create a race of bald-headed, shaggy, half-wild dwarfs, seeing that that had already been done for him by the Creator.

Those to whom this question is a new one will now see what is the point of view of the realist or euhemerist with regard to such traditions. He sees here and there in the past, through much intervening mist, something that looks like a real object, and he tries to define its outlines. He has no intention of denying, as some have vainly imagined, that there is an intervening mist. Nor, it seems necessary to explain, does he assume that wherever there is a mist there must be some tangible object behind it. For example, he does not believe that Boreas, or Zephyrus, or Jack Frost were ever anything but personifications of certain natural forces.[Pg xv]

Various other considerations have also to be borne in mind; not the least important of which is the fact that the very people who have preserved these traditional beliefs have done much to obscure them, owing to their want of education. Scott tells a story of a Scotch peasant who, discovering a company of gaily-dressed puppets standing in a thicket, where they had been concealed by a travelling showman, at once concluded that they were "fairies." He had inherited the belief that fairies were "little people" who frequented just such places as this; consequently, he decided these were fairies. This fact was elicited in court, where the countryman had to appear as a witness. From that time onward his mind ought to have been disabused of his hasty belief. But a man so stupid as to assume that a showman's marionettes were anything else than lifeless dolls, might continue for the rest of his life to recount his marvellous meeting with "the fairies." Similarly, to a tipsy man returning homeward from market, many common and every-day objects take on a weird and superhuman aspect, due to no other spirits than those he has consumed. From this cause, a large number of odd stories (such as one told by Mr. William Black of a tipsy Hebridean) has doubtless arisen. Further, the belief in the existence of "supernatural" beings has been much utilised by rustic humourists, and no doubt also by smugglers and[Pg xvi] other night-birds, in comparatively recent times. The prolonged absence of a husband, or it may be of a wife, could be explained by some wild legend of having been "stolen by the fairies," when a more frank avowal dared not be offered. And although "strange tales were told" regarding the paternity of "Brian," in The Lady of the Lake, and although Scott adheres to those legends in his poem, he does not fail to point out in his appended Note that the story could be explained in a much more rational manner. There have been many "Brians."

To give this subject the special attention which it deserves would, however, swell these introductory notes to an intolerable size; and, indeed, their purpose is rather to show what the euhemeristic theory is than what it is not; that is to say, the euhemeristic theory as applied to the traditions relating to dwarf races.

In the work to which I have referred, the opinions enunciated by Professor Nilsson and Mr. J.F. Campbell, together with other developments which suggested themselves to me, were duly set forth, and were received, as was to be expected, with every form of comment, from complete approval to entire dissent. Among the adverse criticisms, some arose from a misapprehension of the case, while others were due to the critic's imperfect acquaintance with the subject he professed to discuss. But besides these, there were of[Pg xvii] course the legitimate objections which can always be urged in matters of a debateable character, where there is no positive evidence on either side. With regard to such I can at least echo the words of one of the most eminent and most courteous of my opponents, M. Charles Ploix, and say for euhemerism what he says for naturalism:—"Tant que la théorie sur laquelle il s'appuie n'aura pas été démontrée fausse par des arguments décisifs, et surtout tant qu'elle n'aura pas été remplacée par une hypothèse plus certaine, il pourra continuer à s'affirmer."[6]

It ought to be mentioned that the following paper was written for the Folk-Lore Society, at one of whose meetings (in February 1892) it was subsequently read. As, however, the Council of that Society ultimately decided that the paper was unsuited for publication in a journal devoted to the study of folk-lore, it now appears in a separate form. One advantage to be derived from this is that the illustrations which accompanied the lecture, and which are of much importance in enabling one to understand the argument, can also be reproduced at the same time. It may be added that, while the theme is capable of much amplification,[7] have preferred to print the paper[Pg xviii] as it was written for the occasion referred to. It states, concisely enough, the leading points of the argument.

To those who are interested in the "realistic" interpretation of such traditions, I beg to recommend for reference the following works:—First and foremost, there is "The Anatomy of a Pygmie," by Dr. Edward Tyson (London, 1699), a book full of suggestive notices. This author has undoubtedly reached the "bed-rock" of the question; but, owing to his era and mental environment, he has not realised that his argument is useless without a consideration of the various stratifications above the "bed-rock." Belonging to the same century is the chapter "Of Pigmies" in Sir Thomas Browne's "Vulgar Errors," wherein he makes several very interesting statements, although he argues from the opposite side. Scattered throughout the writings of Sir Walter Scott, both poetry and prose, there are also many references bearing upon this question, from the realistic point of view. In addition to these, there is his well-known treatise "On the Fairies of Popular Superstition," prefaced to "The Tale of Tamlane," wherein he states that "the most distinct account of the duergar [i.e. dwergs, or dwarfs], or elves, and their attributes, is to be found in a preface of[Pg xix] Torfæus to the history of Hrolf Kraka [Copenhagen, 1715], who cites a dissertation by Einar Gudmund, a learned native of Iceland. 'I am firmly of opinion,' says the Icelander, 'that these beings are creatures of God, consisting, like human beings, of a body and rational soul; that they are of different sexes, and capable of producing children, and subject to all human affections, as sleeping and waking, laughing and crying, poverty and wealth; and that they possess cattle and other effects, and are obnoxious to death, like other mortals.' He proceeds to state that the females of this race are capable of procreating with mankind;[8] and gives an account of one who bore a child to an inhabitant of Iceland, for whom she claimed the privilege of baptism; depositing the infant for that purpose at the gate of the churchyard, together with a goblet of gold as an offering."[9] Scott further cites from Jessen's De Lapponibus similar matter-of-fact details obtained on this subject from the Lapps; who, on their own showing, are inferentially the half-bred descendants of dwarfs.[Pg xx]

"That some of the myths of giants and dwarfs are connected with traditions of real indigenous or hostile tribes is settled beyond question by the evidence brought forward by Grimm, Nilsson, and Hanusch," observes Dr. E.B. Tylor.[10] And although that eminent anthropologist sees a different meaning in many kindred traditions, yet his observations, and the great mass of references which he gives in connection with this single detail, are of much interest to euhemerists pure and simple. The late Sir Daniel Wilson's "Caliban"[11] teems with the realistic doctrine, and so also does a work of (in my opinion) less equal merit, "The Pedigree of the Devil,"[12] by Mr. Frederic T. Hall. In Mr. R.G. Haliburton's "Dwarfs of Mount Atlas: with notes as to Dwarfs and Dwarf Worship,"[13] and also in his "Further Notes"[14] on that subject, the same idea is prominent. All of these writers, with the exception of Sir Thomas Browne (and excluding Dr. Tylor in so far as regards some of his deductions), refer practically, though in varying degrees, to the question discussed by Tyson; and in this respect I must also cite my recent work on "The[Pg xxi] Aïnos" (pp. 51-66). Of other writers who have not probed quite so deeply, and who possibly may not recognise the necessity for so doing, but who are realists nevertheless, the following may be mentioned: M. Paul Monceaux, who, in the Revue Historique of October 1891, deals with the African dwarfs of ancient and modern writers;[15] Professor Henri van Elven, the main theme of whose forthcoming work, Les Nains préhistoriques de l'Europe Occidentale, formed the subject of a paper recently read by him before the Société d'Archéologie de Bruxelles; and MM. Grandgagnage and De Reul, cited by Mr. C. Carter Blake, F.G.S., in connection with the Nutons of the Belgian bone-caves;[16] as also another writer of the Low Countries, Van den Bergh ("xxx. and 313"), whom Mr. J. Dirks quotes at p. 15 of his Heidens of Egyptiërs, Utrecht, 1850. In Mr. W.G. Black's charming book on Heligoland,[17] one passage (p. 72) recognises that a certain Sylt tradition "is evidently one of those valuable legends which illuminate dark pages of history. It clearly bears[Pg xxii] testimony to the same small race having inhabited Friesland in times which we trace in the caves of the Neolithic age, and of which the Esquimaux are the only survivors." For many of the kindred traditions in that locality, one cannot do better than refer to Mr. Christian Jensen's Zwergsagen aus Nordfriesland, contributed to the Zeitschrift des Vereins für Volkskunde (Berlin, Heft 4, 1892).

[The foregoing pages were all in type before the appearance of Vol. VIII. of the Bibliothèque de Carabas, which contains several criticisms by Mr. Andrew Lang on my "Testimony of Tradition" and "Underground Life." The already excessive length of this Introduction prevents me from now referring more particularly to these observations, as I should otherwise have done. In the meantime, however, I beg to refer Mr. Lang to the present work, and to ask him whether he thinks the statements there quoted substantiate his conception of the Fir Sidhe as a deathless people, occupying some region "unknown of earth."

An addition to the Bibliography of this subject is made in the above-named volume (p. 88). "In his Scottish Scenery (1803), Dr. Cririe suggests that the germ of the Fairy myth is the existence of dispossessed aboriginals dwelling in subterranean houses, in some places called Picts' houses, covered with artificial mounds. The lights seen near the mounds are lights actually carried by the mound-dwellers." Mr. Lang adds: "Dr. Cririe works out in some detail 'this marvellously absurd supposition,' as the Quarterly Review calls it (vol. lix. p. 280)."]

[1] The Testimony of Tradition. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., London, 1890.

[2] Such as at pp. ci.-cix. of Vol. I., and pp. 46, 101, and 275 of Vol. II.

[3] Scott, however, had only imperfectly grasped this idea. In numerous passages he inconsistently refers to "the little people" as purely the creatures of imagination.

[4] A description of those dwarfs, obtained from Japanese records and pictures, may be seen in my monograph on "The Aïnos" (Supplement to Vol. IV. of the Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, Leiden, 1892). Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., London.

[5] Similarly, the "little Bushmen" referred to by Miss Olive Schreiner's Waldo (as quoted by me on the title-page) would be remembered with as much uncertainty a century hence if the modern population of South Africa had nothing but tradition to depend upon. (It may be explained, in case of misapprehension on the part of any too-literal reader, that that quotation is not supposed to prove that the earth-dwellers of the Hebrides were small and ugly, with "little yellow faces," any more than it proves the reindeer of Scotland to have been identical with the wild buck of South Africa. But the cases are analogous, and the quotation seems à propos.)

[6] Le Surnaturel dans les Contes Populaires, Paris, 1891, p. iv.

[7] Some portions of it I have already amplified: in a pamphlet entitled "The Underground Life," Edinburgh, 1892 (privately printed); in a paper on "Subterranean Dwellings," contributed to The Antiquary (London: Elliot Stock) of August 1892; and at pp. 52-58 of "The Aïnos," previously quoted.

[8] By "mankind" need only be understood the race to which Einar Gudmund belonged. It is well known that many races apply the term "men" to themselves alone. At the same time, Gudmund's words may denote a very marked difference in the two types.

[9] Scott again quotes this story, in fuller detail, in the Appendix to The Lady of the Lake, Note 3 C.

[10] "Primitive Culture," vol. i. p. 385 (3rd edition).

[11] London, Macmillan and Co., 1873.

[12] London, Trübner and Co., 1883.

[13] London, David Nutt, 1891.

[14] Asiatic Quarterly Review, July 1892.

[15] For an exhaustive account of "The Pygmy Tribes of Africa," treated from the purely scientific and ethnological point of view see Dr. Henry Schlichter's articles in The Scottish Geographical Magazine of June and July 1892.

[16] Memoirs of the Anthropological Society of London, vol. iii. 1870, pp. 320, 321.

[17] Blackwood and Sons, 1888.

FIANS, FAIRIES AND PICTS.

The general belief at the present day is that, of the three designations here classed together, only that of the Picts is really historical. The Fians are regarded as merely legendary—perhaps altogether mythical beings; and the Fairies as absolutely unreal. On the other hand, there are those who believe that the three terms all relate to historical people, closely akin to each other, if not actually one people under three names.

To those unacquainted with the views of the realists, or euhemerists, it is necessary to explain that the popular definition of Fairies as "little people" is one which that school is quite ready to accept. But the conception of such "little people" as tiny beings of aërial and ethereal nature, able to fly on a bat's back, or to sip honey from the flowers "where the bee sucks,"[Pg 24] is regarded by the realists as simply the outcome of the imagination, working upon a basis of fact. An illustration of this position may be seen in the Far East. There is a tradition among the Aïnos of Northern Japan that they were preceded by a race of "little people," only a few inches in height, whose pit-dwellings they still point out. But the pottery and the skeletons associated with these habitations show that not only were their occupants of a stature to be measured by feet rather than by inches, but also that, by reason of a certain anatomical peculiarity common to both, the traditional dwarfs were very clearly the ancestors of the Aïnos—a race which, though now blended, was once most distinctly a race of dwarfs, if one is to believe the earliest Japanese pictures of them. Similarly, the dwarfs of European tradition are believed to have had as real an origin as the little people of Aïno legend, at any rate by those who hold the realistic theory.

Any attempt to reconcile the pygmies of the classic writers with actual dwarfs of flesh and blood is outside my province. Moreover, this[Pg 25] has been admirably, and, as it seems to me, successfully done quite recently by M. Paul Monceaux, in an article in the Revue Historique,[18] wherein he compares the traditional and historical descriptions with the statements of modern travellers, and draws the inference that the pygmies of the Greek and Roman writers, sculptors and painters, are all derived from actual dwarfs seen by their forefathers in Africa and India. (Still less doubt is there with regard to the dwarfs in Ancient Egyptian paintings.) And whereas Strabo is, says M. Monceaux, the only writer of antiquity who questions the existence of the dwarfs, all the others are on the side of Aristotle, who says—"This is no fable; there really exists in that region (the sources of the Nile), as people relate, a race of little men, who have small horses and who live in holes." And these little men were of course the ancestors of Schweinfurth's and Stanley's dwarfs.

But although M. Monceaux confines his identification to equatorial Africa and to India, he does[Pg 26] not omit to state that Pliny and other writers speak of dwarf tribes in other localities, and among these are "the vague regions of the north, designated by the name of Thule." This area, vague enough certainly, is the territory with which Fians and Picts are both associated; as, also, of course, the Fairies of North European tradition.

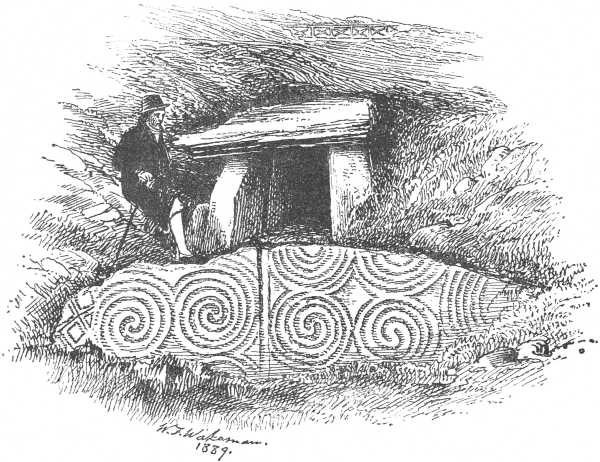

The attributes with which the "little people" of North Europe are accredited cannot be given in detail here. It is enough to note that they were believed to live in houses wholly or partly underground, the latter kind being described as "hollow" mounds, or hills; that when people of taller race entered such subterranean dwellings (as occasionally they did) they found the domestic utensils of the dwarfs were of the kind labelled "pre-historic" in our antiquarian museums; that the copper vessels which dwarf women sometimes left behind them when discovered surreptitiously milking the cows of their neighbours, were likewise of an antique form; further, that they helped themselves to the beef and mutton of their neighbours, after having shot the animals with flint-headed arrows; that melodies peculiar to them are still[Pg 27] sung by the peasants of certain localities; that words used by them are still employed by children in their games; and that many families in many districts are believed to have inherited some of their blood.[19] Of this intercourse between the taller races and the dwarfs, there are many records in old traditions. In the days of King Arthur, when, as Chaucer tells us, the land was "ful-filled of faërie," the knights errant had usually a dwarf as attendant. One of King Arthur's own knights was a Fairy.[20] According to Highland tradition, every high-caste family of pure Gaelic descent had an attendant dwarf. These examples show the "little people" in a not unfriendly light. But many other stories speak of them as "malignant" foes, and as dreaded oppressors. Of which the rational explanation is that these various tales relate to various localities and epochs.[Pg 28]

The connection visible between Fians and Fairies, between Fians and Picts, and between Picts and Fairies, may now briefly be stated.

The earliest known association of the first two classes occurs in an Irish manuscript of the eleventh or twelfth century,[21] wherein it is stated that when the ninth-century Danes overran and plundered Ireland, there was nothing "in concealment under ground in Erinn, or in the various secret places belonging to Fians or to Fairies" that they did not discover and appropriate. This statement receives strong confirmation from a Scandinavian record, the Landnáma-bok, which says[22] that, in or about the year 870, a well-known Norse chief named Leif

"went on warfare in the west. He made war in Ireland, and there found a large underground house; he went down into it, and it was dark until light shone from a sword in the hand of a man. Leif killed the man, and took the sword and much property.... He made war widely in Ireland, and got much property. He took ten thralls."

Although the Scandinavian record does not[Pg 29] speak of the owner of the earth-house as either a "Fian" or a "Fairy," it is quite evident that this is an example of the plundering referred to in the Irish chronicle, and that the Gaels of Ireland seven or eight centuries ago, if not a thousand years ago, regarded the underground people as indifferently Fians and Fairies.[23]

Many other associations of Fians with Fairies are to be seen. In one of the old traditional ballads regarding the Fians, they are described as feasting with Fairies in one of their "hollow" mounds.[24] A Sutherlandshire story relates the adventures of the son of a Fairy woman, who took service with Ossian, the king of the Fians.[25] One of the Fians (Caoilte) had a Fairy sweet-heart.[26] Another of them (Oscar) has an interview with a washerwoman who is a Fairy.[27] A Fenian story recounts how one day the Fians were working in the harvest-field, in the Argyleshire island of Tiree, and on that occasion they[Pg 30] had "left their weapons of war in the armoury of the Fairy Hill of Caolas";[28] from which one is to infer that the Fians made use of Fairy dwellings. In the same collection of tales we are told[29] that one time when the Fians were hunting in the Isle of Skye, they left their wives in a dwelling which bore a title "applied to dwellings of the Elfin race." It is further stated that one popular belief in the Scottish Highlands is that the Fians are still lying in the hill of Tomnahurich, near Inverness, and that "others say they are lying in Glenorchy, Argyleshire."[30] Now, both the Inverness-shire mound and the mounds in Glenorchy are also popularly regarded as the abodes of Fairies.[31] The vitrified fort on Knock-Farril, in Ross-shire, is said to[Pg 31] have been one of Fin McCoul's castles;[32] and Knock-Farril, or rather "a knoll opposite Knock-Farril" is remembered as the abode of the Fairies of that district.[33] Glenshee, in Perthshire, is celebrated equally as a Fairy haunt and as a favourite hunting-ground of the Fians. The Fians, indeed, were said to have lived by deer-hunting, so much so that Campbell of Islay suggests that their name signifies "the deer men"; and the deer, it is believed, "were a fairy race."[34] The famous hound of the famous leader of the Fians was "a Fairy or Elfin dog." In short, the connection between Fians and Fairies, recognised in the Gaelic manuscript of eight or ten centuries ago, is apparent throughout the traditions of the Gaelic-speaking people.

But if the Fians were either identical with, or closely akin to the Fairies, they must have been "little people." The belief that they were so is supported by one traditional Fenian story.[Pg 32] This is the well-known tale of the visit of Fin, the famous chief of the Fians, to a country known to him and his people as "The Land of the Big Men." The story tells how Fin sailed from Dublin Bay in his skin-boat, crossed the sea to that country, and shortly after landing was captured and taken to the palace of the king, where he was appointed court dwarf,[35] and remained for a considerable time the attached and faithful adherent of the king. The collector of this story has assumed that it is purely imaginary. But let it be contrasted with the following extract from the Heimskringla. The period is the early part of the eleventh century, and the scene Norway: "There was a man from the Uplands called Fin the Little, and some said of him that he was of Finnish race. He was a remarkable [? remarkably] little man, but so swift of foot that no horse could overtake him.... He had long been in the service of King Hrorek, and often employed in errands of trust.... Now when King Hrorek was set under guards on the[Pg 33] journey Fin would often slip in among the men of the guard, and followed, in general, with the lads and serving-men; but as often as he could he waited upon Hrorek, and entered into conversation with him."[36] And, like Fin the dwarf in the Gaelic story, this little Fin rendered great service to his king. Now, the Heimskringla Fin is unquestionably a historical personage, and the account of him was written by a twelfth century historian. The Gaelic story was only obtained in the Hebrides, and reduced to writing twenty-three years ago. Although Fin of the Fians is stated in Irish records to be the grandson of a Finland woman,[37] and although the Scandinavian and the Hebridean tales look very much like two versions of one story, this cannot precisely be the case, as the Fenian Fin is placed in an earlier era than his namesake of Norway. A dwarf king named Fin is also remembered in[Pg 34] Frisian tradition;[38] and that he and his race were small men is pretty clearly proved by the fact that when one of the earth-houses attributed to him was opened some years ago, it was found to contain the bones of a little man.[39] Both of these dwarf Fins, Little Fin of Norway and Little Fin of Denmark, are undoubtedly real; and there seems no good reason to suppose that the dwarf Fin of Hebridean tradition was not equally real. Whether they were three separate people is a problem. "Fin" appears to have been at one time a not uncommon name, whatever its etymology and that of "Fian" may be. At any rate, there is nothing in history (which speaks of a close intercourse between Scandinavia and the British Isles, in former times), and nothing[Pg 35] in the ethnology of North-Western Europe, to make us regard as mythical the capture and enthralment of any one of these three "little Fins." If Fin of the Fians, therefore, was a typical Fian, they were little people.[40]

In regarding the Fians as a race of dwarfs, I do not overlook the fact that they are also spoken of as "giants." But to assume them to have been of gigantic stature is both totally at variance with the bulk of the evidence regarding them, and at variance with the fact that the word "giant" has very frequently been used to denote a savage, or a cave-dweller.[41] No more appropriate illustration[Pg 36] of this can be found than the local tradition that a certain artificially hollowed rock in the island of Hoy, Orkney, was the abode of "a giant and his wife." Now, this same "giant" is also remembered as a "dwarf," and the largest cell in his dwelling is only 5 feet 8 inches long. Similarly,[Pg 37] there is in Iceland a certain Tröllakyrkia (literally "the dwarfs' church") which is translated "the giants' church."[42] For these reasons, then, I do not regard any reference to the Fians as "giants" as indicating that they were of tall stature; although I see no objection to the assumption that they were savages and cave-dwellers.

Fians, then, are closely connected with the "little people" called "Fairies." The connection between Fians and Picts is equally well marked.

Regarding them historically, Dr. Skene identi[Pg 38]fies the Fians with one or other of two historical races believed to have occupied Ireland before the coming of the Gaels. These two races are known in Irish story as the Tuatha De and the Cruithné.[43] Now, the Tuatha De are the Fairies of Ireland.[44] Therefore, according to Dr. Skene, the Fians were either Fairies or Cruithné. Now, Cruithné is simply a Gaelic name for the Picts. Consequently, the Fians were either Fairies or Picts—according to Dr. Skene. In one traditional story, already referred to, the Fians seem to be unhesitatingly regarded as Picts. This story, obtained in Sutherlandshire, tells how a certain king lived for a year with a banshee, or fairy woman,[45] by whom he had a son. When this son grew up he went to the country of the Fians,[46] and there he entered[Pg 39] into the service of their king, who was no other than the celebrated Oisin. The Gaelic narrator calls him "Oisin, Righ na Feinne," that is, "Ossian, King of the Fians"; but the collector of the story,[47] who had no doubt obtained the translation on the spot, renders Righ na Feinne as "King of the Picts." No explanation or comment is given, and one is therefore led to infer that in Sutherlandshire Feinne is without question regarded as a Gaelic name for the Picts. This identity is, indeed, borne out otherwise. There is a Gaelic saying in Glenlyon, Perthshire, to the effect that "Fin had twelve castles" in that glen, and the remains of these "castles," all said to have been built by him and his Fians, and of which one in particular is styled "Castle Fin,"[48] are known to the English-speaking people of Scotland as "Picts'" houses. For they belong to a peculiar class of structures, all radically alike, and all known, in certain districts, as "Picts' houses." The term "Picts' house" is unknown in the Hebrides, says[Pg 40] one writer. "In the Hebrides tradition is entirely silent concerning the Picts ... there the Fenian heroes are the builders of the duns."[49] Yet the self-same class of building is elsewhere assigned to the Picts. To these structures I shall presently refer more particularly; but it is enough to note in passing that, just as Oisin, King of the Fians, is translated into Ossian, King of the Picts, so the dwellings ascribed to the Fians in one locality, are in another said to have been made and inhabited by the Picts.

Fians, then, are associated or identified with Fairies, and also with Picts. To complete my equilateral triangle, the Picts ought also to be regarded as Fairies, or as akin to them.

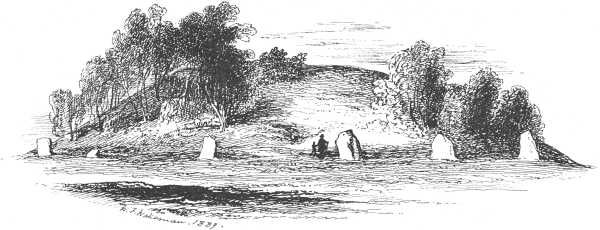

This undoubtedly is a popular belief. The earliest alleged reference of this kind is placed by one writer in the middle of the fifteenth century, before the Orkney Islands had passed from the crown of Denmark to the crown of Scotland. A manuscript of the then Bishop of Orkney, dated Kirkwall 1443, states that when Harald Haarfagr conquered the Orkneys in the ninth century, the[Pg 41] inhabitants were the two "nations" of the Papæ and the Peti, both of whom were exterminated. By the former name is understood the Irish missionaries: the Peti were certainly the Picts, or Pehts.[50] Now, of these Picts of Orkney it is said, that they "were only a little exceeding pigmies in stature, and worked wonderfully in the construction of their cities, evening and morning, but in mid-day, being quite destitute of strength, they hid themselves through fear in little houses under ground."[51]

[Pg 42]The exact date of this statement is at present doubtful, but it is quite in accordance with the widespread ideas held throughout Scotland and Northumberland with regard to the Picts: that they were great as builders, but were of very low stature, and closely akin to Fairies.[52] Moreover, they are famous for doing their work during the night. Whatever be the explanation of the above curious statement that at mid-day they lost their strength and withdrew to their underground houses, it is at any rate interesting to compare with it the remark made by the traveller Pennant as he was passing along Glenorchy in 1772. This is the entry in his journal:—"See frequently on the road-sides small verdant hillocks, styled by the common people shi an (sithean), or the Fairy-haunt, because here, say they, the fairies, who love not the glare of day, make their retreat after[Pg 43] the celebration of their nocturnal revels."[53] Now, as the "Picts' houses" are, to outward appearance, "small verdant hillocks," the parallel is very exact. With these two references compare also the mention, in a quaint old gazetteer printed at Cambridge in 1693,[54] of the tribe of the "Germara," defined as "a people of the Celtæ, who in the day-time cannot see." Although the author usually gives the sources of his information, in this instance he gives none. But the statement agrees perfectly with the belief found everywhere throughout Northern Europe that "the dwarfs could not bear daylight, and during the day hid in their holes."[55] It really seems impossible to avoid the inference that all this was perfectly true. When Leif went down into the underground house in Ireland, he could not see at first, though at length he saw in the obscurity the glimmer of his opponent's sword. Consequently, the denizens and[Pg 44] builders of these subterranean retreats must either have had something very like "cat's eyes," or else they must in general have had numerous lamps burning. This will be understood by an examination of one or two of the accompanying diagrams. It seems to me beyond question that a people living this underground life must have differed very distinctly from ourselves in the matter of vision; and to them the brightness of noonday must have been blinding. This physical fact—if it be a fact—would explain much that is otherwise strange and incredible in the traditions relating to the Picts—or Pechts, as they were formerly called in Scotland. However, it is sufficient for my present purpose to note that this peculiarity associates, and indeed identifies, the Picts with the dwarfs or fairies of tradition.

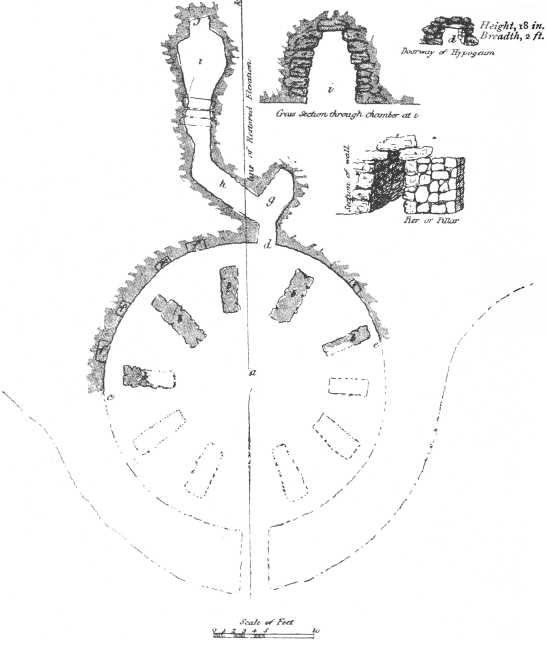

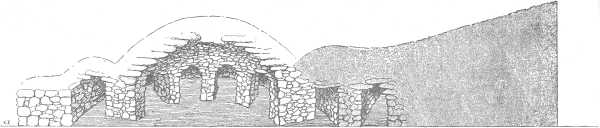

Having thus shown that Fians, Fairies, and Picts are so closely associated as to be, in some aspects, almost indistinguishable from one another, I shall now refer to the structures which are popularly believed to have been their dwellings. Some of these are wholly underground, others partly so, and others quite above ground. In many other[Pg 45] ways, also, they vary. But all of them are unquestionably links in one special style of structure; of which the most marked feature, or at any rate that which is common to all, is the use of what is called the "cyclopean" arch. This is formed by the overlapping of the stones in the wall until they almost meet at the dome or apex of the building, when a heavy "keystone" completes this rude arch. The principle of the arch proper was obviously quite unknown to the originators of such structures.

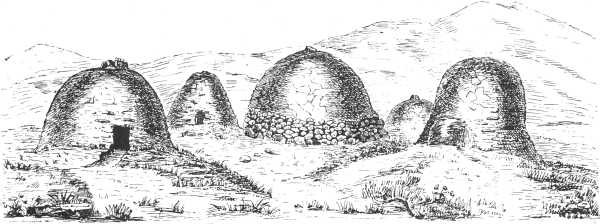

Of the various Hebridean specimens of these buildings, very interesting and complete descriptions have been given by the late Captain Thomas, R.N.,[56] and Sir Arthur Mitchell,[57] who visited some of them together in 1866. Referring to the most modern examples of this kind of structure, the latter writer says:—"They are commonly spoken of as beehive houses, but their Gaelic name is bo'h or bothan. They are now only used as temporary residences or shealings by those who herd[Pg 46] the cattle at their summer pasturage; but at a time not very remote they are believed to have been the permanent dwellings of the people." And he thus describes his first sight of the beehive houses:—

"I do not think I ever came upon a scene which more surprised me, and I scarcely know where or how to begin my description of it.

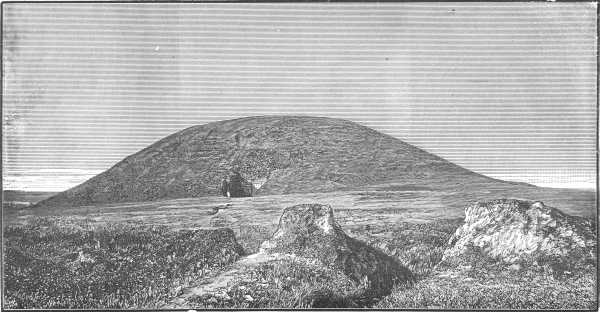

"By the side of a burn which flowed through a little grassy glen ... we saw two small round hive-like hillocks, not much higher than a man, joined together, and covered with grass and weeds. Out of the top of one of them a column of smoke slowly rose, and at its base there was a hole about three feet high and two feet wide, which seemed to lead into the interior of the hillock—its hollowness, and the possibility of its having a human creature within it being thus suggested. There was no one, however, actually within the bo'h, the three girls, when we came in sight, being seated on a knoll by the burn-side, but it was really in the inside of these two green hillocks that they slept, and cooked their food, and carried on their work, and—dwelt, in short."[58]

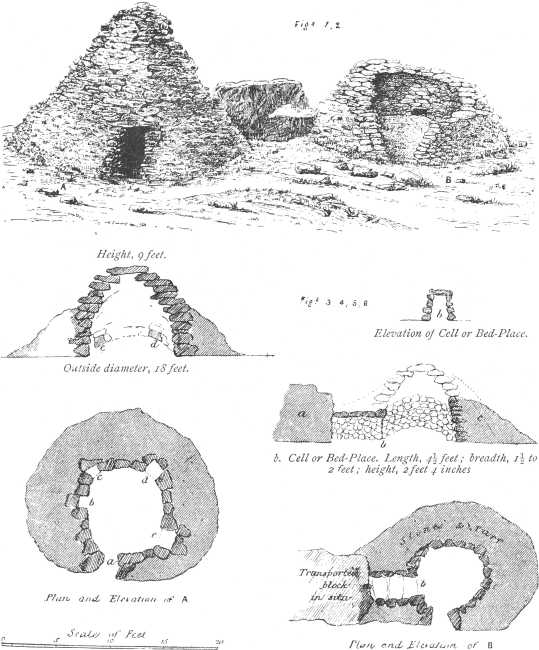

These two "green hillocks," and other structures of the same nature, are shown in the accompanying diagrams[59] (Plates I.-XVI.), which explain their formation better than any written[Pg 47] description. It is enough here to state that they are built of rough stone, without any mortar. "Though the stone walls are very thick," says my authority (p. 62), "they are covered on the outside with turf, which soon becomes grassy like the land round about, and thus secures perfect wind and water tightness." Sometimes they occur in groups, as those shown in Plate III.; of which scene Captain Thomas justly remarks that "at first sight it may be taken for a picture of a Hottentot village rather than a hamlet in the British Isles."[60] Here there is little or no grassy covering outside, however; and consequently none of the hillock-like effect. But this is very well shown in Plates VI. and VIII. Of the "agglomeration of beehives" pictured in the latter, Sir Arthur Mitchell observes:—"It has several entrances, and would accommodate many families, who might be spoken of as living in one mound, rather than under one roof" (op. cit. pp. 64-5). Of another such dwelling, now ruined, he says that it could have accommodated "from forty to fifty people."[Pg 48]

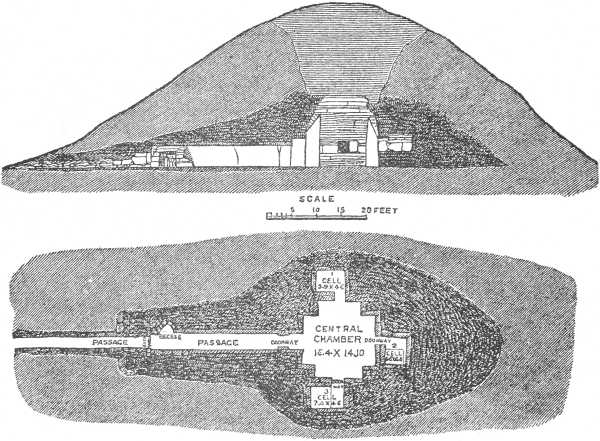

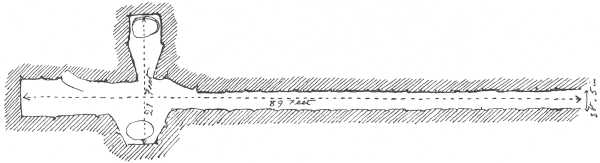

This last, however (Plates XI. and XII.), represents another variety of earth-house, the chambered mound or beehive, with an underground gallery leading to it. Of this kind two examples are here shown. And in Plates I. and XIII. will be seen specimens of wholly subterranean structures. It is difficult, and indeed hardly necessary, to distinguish between one variety and another of what is practically the same kind of building; but to this last class the term "earth-house" is most frequently accorded in Scotland. In the broader dialect it is "yird-house" or "eirde-house," which at once recalls the form "jord-hus" in the saga which tells of Leif's adventure underground in Ireland. The term weem is also applied to these places in Scotland. This is merely a quickened pronunciation of the Gaelic uam (or uamh), a cave; and it reminds one that, both in Gaelic and in English, the word "cave" is by no means restricted to a natural cavity. Indeed, one of the two artificial structures under consideration is known as Uamh Sgalabhad, "the cave of Sgalabhad." Another old Gaelic name for those[Pg 49] underground galleries is "tung or tunga";[61] while another name, by which they are known in Lewis is tigh fo thalaimh,[62] or "house beneath the ground."

"Martin, in his description of the Western Islands, printed in 1703, when their use would appear to have been still remembered, speaks of them [these underground structures] as 'little stone-houses, built under ground, called earth-houses, which served to hide a few people and their goods in time of war.'"[63] Dean Monro writes, "There is sundry coves and holes in the earth, coverit with hedder above, quhilk fosters many rebellis in the country of the North head of Ywst" [North Uist].[64] "From O'Flaherty's description of West Connaught, written in 1684, it appears," observes Captain Thomas,[65] but[Pg 50] referring more strictly to the beehive-house, "that this style of dwelling had already become archaic." For, although that writer mentions certain "cloghans" as being still inhabited, holding forty men in some cases, yet he says they were "so ancient that nobody knows how long ago any of them were made." Of the underground galleries another writer says: "It has been doubted if these houses were ever really used as places of abode.... But as to this there can be no real doubt. The substances found in many of them have been the accumulated débris of food used by man.... Ornaments of bronze have been found in a few of them, and beads of streaked glass. In some cases the articles found would indicate that the occupation of these houses had come down to comparatively recent times."[66]

In conclusion, these remarks of Captain Thomas, who made so thorough a study of the subject, may be quoted:—

"The Pict's house on the Holm of Papay [Orkney] would have held, besides the chiefs at each end, all the families in [the island of] Papay Westray when it was built. Maes howe[67][Pg 51] was for three families—grandees, no doubt; but the numbers it was intended to hold in the beds may be learned by comparing them with the Amazon's House, St. Kilda."[68]

"I consider the relation between the boths [beehive houses] and the Picts' houses of the Orkneys (and elsewhere) to be evident—the same method of forming the arch, the low and narrow doors and passages, the enormous thickness of the walls, when compared with the interior accommodation—exist in both. When a both is covered with green turf it becomes a chambered tumulus, and when buried by drifting sand it is a subterranean Pict's house.... I regard the comparatively large Picts' houses of the Orkneys as the pastoral residence of the Pictish lord, fitted to contain his numerous family and dependents. Such an one exists on the Holm of Papa Westray, which, according to the Highland method of stowage, would certainly contain a whole clan. When writing the description of it, I had not made acquaintance with a people who would close the door to keep in the smoke, or that nested in holes in a wall like sand-martins....

"But the both of the Long Island is only the lodging of the common man or 'Tuathanach,' and is consequently of small dimensions, and not remarkable for comfort. If the modern Highland proprietor or large farmer should ever be induced to lead a pastoral life, and adopt a Pictish architecture in his residence, we might again see a tumulus of twenty feet in height, with its long low passage leading into a large hall with beehive cells on both sides."[69]

But the point of all this is that these dwellings, whether above ground or below, are known as[Pg 52] Picts' Houses, Fairy Halls, Elf Hillocks, "the hidden places of Fians and Fairies." Thus, the three titles which I have shown to be associated in other ways are all given to the alleged builders and occupiers of those very archaic and peculiar structures.

It is true that, in their most modern form, some of those dwellings are still inhabited for months at a time. And their inhabitants are neither Fians, Fairies nor Picts. But it is among those people that stories of Fians and Fairies are most rife, and many claim an actual descent from them. And although they are certainly not pigmies, yet they live in a district in which the small type of this heterogeneous nation of ours is still quite discernible; and that part of the island of Lewis (Uig), which has longest retained those places as dwellings, is inhabited by a caste whom other Hebrideans describe as small, and regard as different from themselves.[70] Dr. Beddoe states that the tallest people in the United Kingdom[Pg 53] are to be found in a certain village in Galloway, where a six-foot man is perfectly common, and many are above that height. It is quite certain that such men could not "nest like sand-martins" in the holes in the wall described by Captain Thomas. And, in proportion as such Galloway men are to the modern Hebridean mound-dwellers, so are these to the much more archaic race with whom the oldest structures are associated. For a study of the dimensions of these will show that they could not have been conceived, and would not have been built or inhabited by any but a race of actual dwarfs; as tradition says they were.

[18] "La légende des Pygmées et les nains de l'Afrique equatoriale": Rev. Hist. t. 47, I. (Sept.-Oct. 1891), pp. 1-64.

[19] For some of these references see Dr. Hibbert's "Description of the Shetland Islands," Edinburgh, 1822, pp. 444-451. See also Mrs. J.E. Saxby's "Folk-Lore from Unst, Shetland" (in Leisure Hour of 1880); Mr. W.G. Black's "Heligoland", 1888, chap. iv.; and "The Fians," London, 1891, pp. 2-3.

[20] Gwynn the son of Nudd: for whom see Lady C. Guest's "Mabinogion," pp. 223, 263-5, and 501-2.

[21] "The War of the Gaedhil with the Gaill," edited by J.H. Todd, D.D., London, 1867, pp. 114-115.

[22] I. cc. 4-6 (this reference and the passage is quoted from Du Chaillu's "Viking Age," vol. ii. p. 516).

[23] "Fianaibh ag Sithcuiraibh"

[24] "Dan an Fhir Shicair"; Leabhar na Feinne, pp. 94-95.

[25] Folk-Lore Journal, vol. vi. 1888, pp. 173-178.

[26] The Fians, 1891, p. 64.

[27] Ibid. p. 33.

[28] The Fians, p. 172. The Fairy Hill referred to is "a hillock, in which there is to be seen a small hollow called the armoury" (p. 174).

[29] Ibid. pp. 12-13, 166, &c.

[30] Ibid. pp. 3-4. Glenorchy is said to have teemed with Fenian traditions about the early part of this century (Proceedings of Soc. of Antiq. of Scotland, vol. vii. pp. 237-240).

[31] See my Testimony of Tradition, London, 1890, pp. 146-8; and Pennant's "Second Tour in Scotland" (Pinkerton's Voyages, London, 1809, vol. iii. p. 368).

[32] Proceedings of Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. vii. p. 294, note.

[33] See, for example, an article on "Scottish Customs and Folk lore," in The Glasgow Herald of August 1, 1891.

[34] The Fians, pp. 78-80.

[35] Scottish Celtic Review, 1885, pp. 184-90: The Fians, pp. 175-184.

[36] The Heimskringla: Dr. Rasmus B. Anderson's 2nd ed. (1889) of Mr. Samuel Laing's translation from Snorre Sturlason: chap. lxxxiii., Of Little Fin.

[37] Leabhar na Feinne, p. 34.

[Subsequent Note.—To be very accurate, one ought to say that, in the pedigree referred to, Fin's grandfather (Trenmor) is stated to have married a Finland woman.]

[38] Mr. W.G. Black's Heligoland, 1888, chap. iv.

[39] With this Fin of Frisian tradition may be compared Fin, a North-Frisian chief of the fifth century, mentioned in Beowulf and The Gleeman's Tale, and whose death is recorded in The Fight at Finnsburk.

[Subsequent Note.—A suitable companion to the dwarf Fin of Frisian tradition is mentioned in Harald Hardradi's Saga:—"Tuta, a Frisian, was with King Harald; he was sent to him for show, for he was short and stout, in every respect shaped like a dwarf."—Quoted by Mr. Du Chaillu at p. 357 of vol. ii. of "The Viking Age."]

[40] In this connection it is worth noting that Sir Walter Scott, in referring to the aboriginal or servile clans in 1745, whom he describes as "half naked, stinted in growth, and miserable in aspect," includes among them the McCouls, Fin's alleged descendants, who "were a sort of Gibeonites, or hereditary servants to the Stewarts of Appin." (Waverley, ch. xliv.)

[41] For example, the late Rev. J.G. Campbell, Tiree, says of "the Great Tuairisgeul" that he was "a giant of the kind called Samhanaich—that is, one who lived in a cave by the sea-shore, the strongest and coarsest of any" (Scottish Celtic Review, p. 62). That this term was one of contempt, given by Gaelic-speaking people to those "giants" (and apparently based upon their malodorous characteristics), will be seen from Mr. Campbell's further observation (op. cit. pp. 140-141):—"It is a common expression to say of any strong offensive smell, mharbhadh e na Samhanaich, it would kill the giants who dwell in caves by the sea. Samk is a strong oppressive smell." McAlpine defines Samk as a "bad smell arising from a sick person, or a dirty hot place"; and he further gives the definition "a savage" (quoting Mackenzie). The word Samhanach itself is defined by McAlpine as "a savage," and he cites the Islay saying:—"chuireadh tu cagal air na samhanaich," "you would frighten the very savages." From these definitions it will be seen that a word translated "giant" by one is rendered "savage" by another (though neither of these terms expresses the literal meaning). Mr. J.G. Campbell also practically regards it as signifying "cave-dweller," or perhaps a certain special caste of cave-dwellers. With this may be compared McAlpine's "uamh, n.f., a cave, den; n.m., a chief of savages, terrible fellow ... 'cha'n'eil ann ach uamh dhuine,' 'he is only a savage of a fellow.'" Islay has also another word to denote a Hebridean savage. This is ciuthach, "pr. kewach, described in the Long Island as naked wild men living in caves" (J.F. Campbell, Tales, iii. 55, n.). One of these "kewachs" figures in the story of Diarmaid and Grainne, and one version says that he "came in from the western ocean in a coracle with two oars (curachan)" (The Fians, p. 54). (His name assumes various shapes—e.g., Ciofach Mac a Ghoill, Ciuthach Mac an Doill, Ceudach Mac Righ nan Collach.) These three terms—samhanach, uamh dhuine, and ciuthach—all seem to indicate one and the same race of people. And these are probably the people referred to by Pennant when he says, speaking of the civilised races of the Hebrides in the beginning of the seventeenth century:—"Each chieftain had his armour-bearer, who preceded his master in time of war, and, by my author's (Timothy Pont's MS., Advocates' Library, Edinburgh) account in time of peace; for they went armed even to church, in the manner the North Americans do at present [1772] in the frontier settlement, and for the same reason, the dread of savages." (Pinkerton's Voyages, vol. iii. p. 322.)

[42] Hibbert's "Description of the Shetland Islands," Edinburgh, 1822, pp. 444-451. With regard to the "Dwarfie Stone" of Hoy, the following references may be given:—"Jo. Ben," 1529, at p. 449 of Barry's "History of the Orkney Islands," 2nd ed., London, 1808; and other writers subsequent to 1529. These speak of this stone as the abode of a "giant." Sir Walter Scott (The Pirate, Note P.) and many others invariably say "a dwarf."

Note also J.F. Campbell (W.H. Tales, p. xcix): "The Highland giants were not so big, but that their conquerors wore their clothes." Also the dwarf in Ramsay's "Evergreen" who says that he was engendered "of giants' kind."

[43] Dean of Lismore's Book, p. lxxvi.; Celt. Scot., vol. i. p. 131; vol. iii. chap. iii.; &c.

[44] Celt. Scot. iii. 106-7.

[45] In this tale, the phonetic spelling ben-ce shows the unusual aspirated form bean-shithe. She is elsewhere spoken of as the Lady of Innse Uaine, and her son is the hero of the tale Gille nan Cochla-Craicinn.

[46] According to a clergyman of the seventeenth century, the Hebrides and a part of the Western Highlands constituted "the country of the Fians," (Testimony of Tradition, p. 45.)

[47] Miss Dempster: "The Folk-Lore of Sutherlandshire," Folk-Lore Journal, vol. vi. 1888, p. 174.

[48] Proc. of the Soc. of Antiq. of Scot., vol. vii. p. 294.

[49] Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., vol. vii. pp. 165 and 192.

[50] "They are plainly no other than the Peihts, Picts, or Piks ... the Scandinavian writers generally call the Piks Peti, or Pets: one of them uses the term Petia, instead of Pictland (Saxo-Gram.); and, besides, the frith that divides Orkney from Caithness is usually denominated Petland Fiord in the Icelandic Sagas or histories." (Barry's Orkney, p. 115.)

[51] Proc. of the Soc. of Antiq. of Scot., vol. iii. p. 141: also vol. vii. p. 191. This quotation is made by the late Captain Thomas, R.N., a sound archæologist; but I have to add that in the document of 1443, as given in Barry's Orkney (2nd ed., London, 1808, pp. 401-419), while I find the statement as to the two native races, I find nothing about the stature or habits of the Picts. Captain Thomas twice quotes his statement, and as at one place he refers, not to the Bishop of 1443, but (vol. iii. p. 141) to "the Earl of Orkney's chaplain, writing about 1460," it is possible he had two manuscripts of the fifteenth century in view.

[Supplementary Note.—The Bishop's words are as follows:—

"Istas insulas primitus Peti et Pape inhabitabant. Horum alteri scilicet Peti parvo superantes pigmeos statura in structuris urbium vespere et mane mira operantes, meredie vero cunctis viribus prorsus destituti in subterraneis domunculis pre timore latuerunt."—From his treatise De Orcadibus Insulis, reprinted in the "Bannatyne Miscellany," 1855, p. 33.]

[52] Testimony of Tradition, pp. 58-60, 65, 67-74, 79-80.

[53] Pennant's Second Tour in Scotland; Pinkerton's Voyages, London, 1809, p. 368.

[54] Linguæ Romanæ, Dictionarium, Luculentum Novum.

[55] Du Chaillu: Land of the Midnight Sun, vol. ii. pp. 421-2. This also is one of the articles of belief in Shetland, with regard to the trows, as the trolls are there called.

[56] Proc. of Soc. of Antiq. of Scot. (First Series), vol. iii. pp. 127-144; vol. vii. pp. 153-195.

[57] The Past in the Present, Edinburgh, 1880, pp. 58-72.

[58] The Past in the Present, p. 59.

[59] Reproduced by permission of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

[60] Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., vol. iii. p. 137.

[61] Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., vol. vii. p. 168 n. This appears to me to be a phonetic spelling of the diongna mentioned in the passage relating to the plunderings of the Danes in the ninth century.

[62] Ibid. p. 171. On the same page, the form Ugh talamkant is given.

[63] Chambers's Encyclopædia, new ed., s.v. Earth-house.

[64] Quoted in Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., vii. 172. The reference is "Ag. Rep. Heb. p. 782."

[65] Op. cit. vol. iii. p. 140.

[66] John Stuart, LL.D., Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., viii. pp. 23 et seq.

[67] Plates XIV.-XVI. Compare also Plates XVII.-XIX.

[68] Op. cit., vii. 191.

[69] Op. cit., iii. 133.

[70] Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. iii. (First Series), p. 129. The district of Barvas is specially referred to by Captain Thomas.

APPENDIX.

Most of the illustrations here given are reproductions of some of the plates accompanying Captain Thomas's papers in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. In explanation of their details the following extracts may be made.

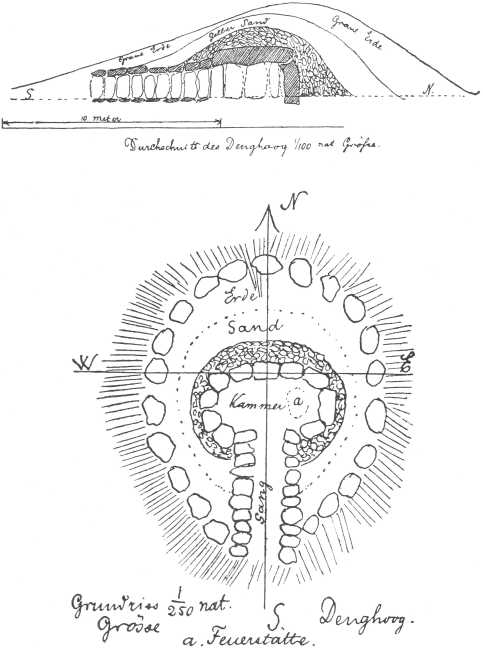

Plate I. (Frontispiece).—Uamh Sgalabhad, South Uist.

(From Plate XXXV. of Vol. VII. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

Captain Thomas thus describes his descent into and exploration of this earth-house:—"An irregular hole was pointed out by the little lassie before alluded to, and some of my party quickly disappeared below ground. As they did not immediately return, I thought it was time to follow, and squeezing through the ruinated entrance (a), I entered the usual kind of gallery, which descended into the ground at a sharp angle. At the bottom, on the right-hand side, was the usual guard-cell (b); the sides of dry-stone masonry, but the end was the face of a rock in situ. Proceeding on, the roof rose and the gallery widened to what was the main chamber (c), which was 7 feet high under the apex of the dome, and 4 feet broad. Upon the west side of this chamber, and about 2 feet from the ground, is a recess, about 2 feet square and 4 feet long. At the further end, and in the same right line,[Pg 56] the gallery (d) became low (2½ feet) and narrow (2 feet). Again the roof rose, and the gallery widened till stopt, in face, by a large transported rock (f); to the right of the rock a rectangular chamber (e), 2 feet broad, extended 4 feet, and ended against rock in situ. Round, and beyond the rock (f), the wall of the left side of the gallery was built, but the passage was so narrow (g) that I contented myself by looking through it. This incomprehensible narrowness is a feature in the buildings of this period. Some of Captain Otter's officers pushed through into the small chamber (h); beyond this the gallery was ruinated and impassable; the total length explored was 45 feet."[71]

[71] Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., vol. vii. (First Series), pp. 167-8.

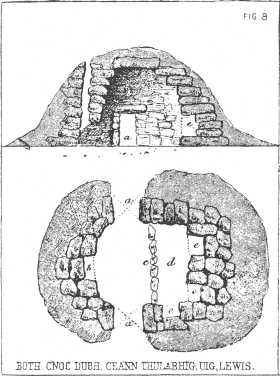

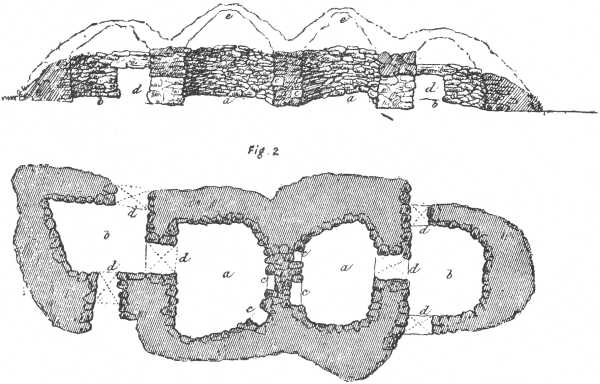

Plate II.—Bee-Hive Houses at Uig, Lewis.

(From Plate XXXI. of Vol. VII. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

Fig. 8. Captain Thomas selects this as "the most modern, and at the same time the last, in all probability, that will be constructed in this manner"—viz., "roofed by the horizontal or cyclopean arch, i.e., by a system of overlapping stones." "The woman who was living in it [about 1869] told us it was built for his shieling by Dr. Macaulay's grandfather, who was tacksman [leaseholder] of Linshader ... and I conclude that it was made about ninety years back."[72]

Fig. 9. Sir Arthur Mitchell says of this compound "bee-hive" house:—"The greatest height of the living room—in its centre, that is—was scarcely 6 feet. In no part of the dairy was it possible to stand erect. The door of communication between the two rooms was so small that we could get[Pg 57] through it only by creeping. The great thickness of the walls, 6 to 8 feet, gave this door, or passage of communication, the look of a tunnel, and made the creeping through it very real. The creeping was only a little less real in getting through the equally tunnel-like, though somewhat wider and loftier passage, which led from the open air into the first or dwelling room."[73]

[72] Op. cit., p. 161.

[73] The Past in the Present, p. 60.

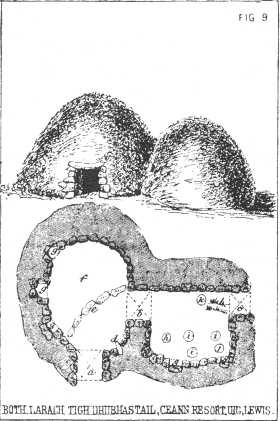

Plate III.—Bee-Hive Houses at Uig, inhabited in 1859.

(From Plate XII. of Vol. III. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

See p. 47, ante.

Plate IV.—Bee-Hive Houses at Meabhag, Forest of Harris.

(From Plate X. of Vol. III. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

At the date of Captain Thomas's visit (1861) a man was still living who had been born in one or other of these dwellings.

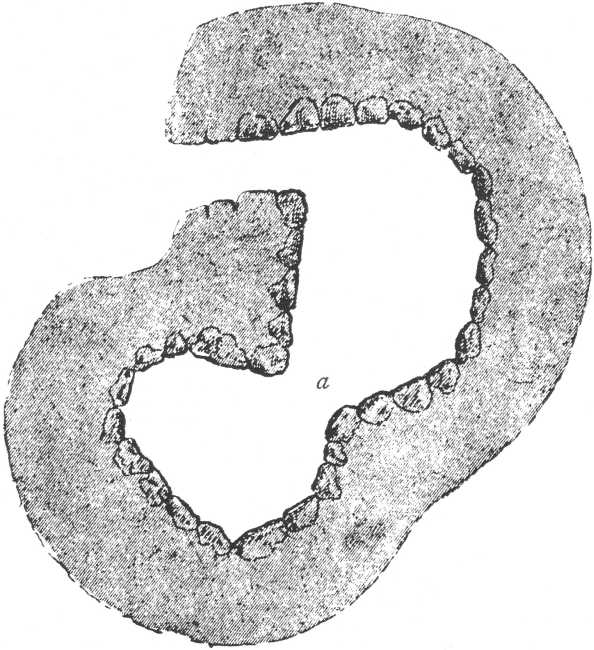

PLATE V.

GROUND PLAN OF RUINED BOTH AT BAILE FHLODAIDH, ON THE NORTH SIDE OF THE ISLAND OF BENBECULA.

a. "scarcely 18 in. wide."

Plate V.—Ground Plan of Bee-Hive House, Island of Benbecula.

(From Plate XXXII. of Vol. VII. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

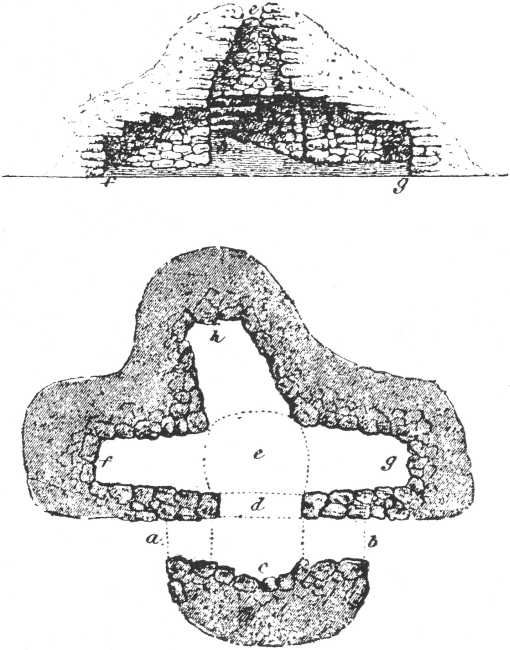

PLATE VI.

SECTIONAL VIEW AND GROUND PLAN OF MOUND DWELLING, CALLED BOTH STACSEAL, SITUATED MIDWAY BETWEEN STORNOWAY AND CARLOWAY, LEWIS, HEBRIDES.

"A hole (e), called the Farlos, is left in the apex of the roof for the escape of the smoke, and is closed with a turf or flat stone as requisite."

Height of Dome, 7 feet.

a, b. Doorways.

c. Fireplace.

d. Row of stones for seats.

e. Centre. (Distance from e to end of cells, 7

feet.)

f, g, h. Cells or bed-places.

f is "2 feet wide and 15 inches high at the inner end; is 5

feet long and 3 feet high at the mouth. The opposite cell (g) is

of the same dimensions. The third cell (h) is 4 feet wide at the

mouth, 5 feet long, decreasing to 2½ feet wide at the

head, where it is 16 inches high."

The above is given by Captain Thomas as an example of such dwellings "having oven-like bed-places around the internal area. This interesting summer house illustrates the most antique form of dormitory; but in the winter houses the floor of the bedroom was raised three or four feet above the ground." (Compare the side cells in Maes-How, Orkney.)

Plate VI.—Chambered Mound (Both Stacseal), near Stornoway, Lewis.

(From Plate XXXII. of Vol. VII. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

With reference to the farlos, or smoke-hole (otherwise "sky-light"), which, in this instance, is at a height of 7 feet from[Pg 58] the floor of the dwelling, Captain Thomas remarks:—"A man, on standing upright, can often put his head out of the hole and look around" (op. cit., vol. iii., p. 130 n.). This suggests the following story, told by Mr. J.F. Campbell (West Highland Tales, vol. ii., pp. 39-40):

"There was a woman in Baile Thangusdail, and she was out seeking a couple of calves; and the night and lateness caught her, and there came rain and tempest, and she was seeking shelter. She went to a knoll with the couple of calves, and she was striking the tether-peg into it. The knoll opened. She heard a gleegashing (gliogadaich) as if a pot-hook were clashing beside a pot. She took wonder, and she stopped striking the tether-peg. A woman put out her head and all above her middle, and she said, 'What business hast thou to be troubling this tulman [mound] in which I make my dwelling?' 'I am taking care of this couple of calves, and I am but weak. Where shall I go with them?' 'Thou shalt go with them to that breast down yonder. Thou wilt see a tuft of grass. If thy couple of calves eat that tuft of grass, thou wilt not be a day without a milk cow as long as thou art alive, because thou hast taken my counsel.'

"As she said, she never was without a milk cow after that, and she was alive fourscore and fifteen years after the night that was there."

a. Dwelling apartments.

b. Fosgarlan or Porch.

c. Cuiltean or Milk cupboards.

d. Stonebench or Bedplace.

AB. Line of Section.

CD. View as represented as restored.

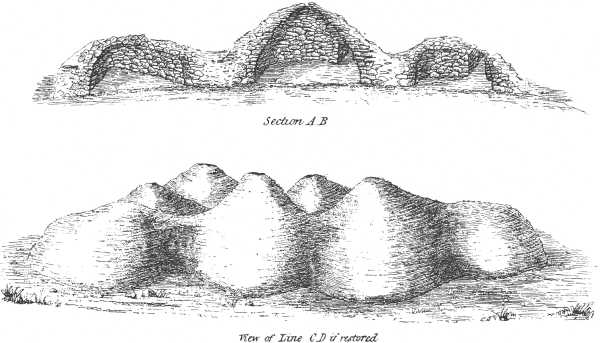

PLATE VIII.

SECTION AND ELEVATION OF BOTHAN GEARRAIDH NA H'AIRDE MOIRE, UIG, LEWIS, HEBRIDES, AND VIEW OF SAME IF RESTORED.

Plates VII. and VIII.—"Agglomeration of Bee-Hives" at Uig, Lewis.

(From Plates XV. and XVI. of Vol. III. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

"By far the most singular of all these structures, and probably unique in the Long Island, is at Gearraidh na h-Airde[Pg 59] Moire, on the shore of Loch Resort. I cannot describe it better than by bidding you suppose twelve individual bee-hive huts all built touching each other, with doors and passages from one to the other. The diameter of this gigantic booth is 46 feet, and [it] is nearly circular in plan. The height of the doors and passages about 2½ feet; and under the smokehole (farlos), in two of the chambers, the height was 6½ feet.... I am informed that, so late as 1823, this both was inhabited by four families." (Captain Thomas, Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot., vol. iii., p. 139.)

a. dwellings.

b. fosgarlan or porch.

c. cuiltean or milk cupboards.

d. doors.

e. farlos or smokehole.

"One of a group of three at the garry of Aird Mhor, close to the shore and near the mouth of Loch Resort, Uig, Lewis. This compound both has evidently been intended for two related families ... but there is no interior communication between the dwellings." (Op. cit. p. 144.)

Plate IX.—Compound "Both" situated near the above.

(From Plate XIV. of Vol. III. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

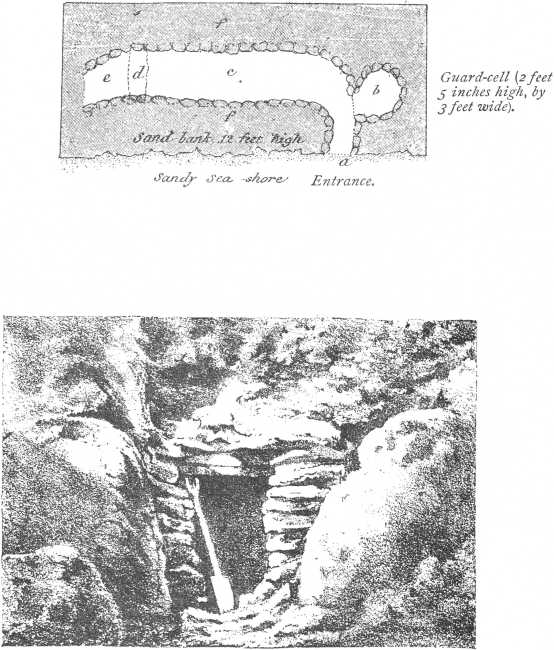

PLATE X.

GROUND PLAN AND SECTIONAL VIEW OF SEMI-SUBTERRANEAN BOTH AND UNDERGROUND GALLERY, MEAL NA H-UAMH, MOL A DEAS, HUISHNISH, ISLAND OF SOUTH UIST.

Plate X.—"Both" and Underground Gallery at Meall na h-Uamh, Huishnish, South Uist.

(From Plate XXXIII. of Vol. VII. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

"I have next to notice," says Captain Thomas (op. cit., p. 164), "that form of bo'h, Pict's house, or clochan, whichever name may be adopted by archæologists, to which a hypogeum or subterranean gallery is attached.... [The present example] is in South Uist, about half a mile inland from Moll a Deas (South Beach); and the Moll is about one mile and a half to the south of Husinish (Husness, i.e., Houseness). The site of the bo'h is called Meall na [h-] Uamh, or Cave Lump [more correctly, the Mound of the Cave, or 'Weem.'] It consists of a partly excavated oval dwelling chamber (a), 7 feet by 14 feet on the floor; the dome roof has fallen in; there are two cuiltean, or niches in the wall. A low curved subterranean passage (b), about 2½ feet square and[Pg 60] 20 feet in length, leads into an elongated bee-hive chamber (c), 13 feet by 5 feet, and 6¾ feet high; from thence an entrance (d), 2 feet by 2 feet, admits to a small circular chamber or cell (e), 5 feet in diameter and 5 feet high. The main passage inclines downwards, so that the floor of the second chamber (c) is nearly 3 feet lower than that of the first (a); and that of the inner one (e) a foot below the second (c)."

PLATE XI.

GROUND PLAN OF BOTH AND UNDERGROUND GALLERY, OR TIGH LAIR, NEAR MOL A DEAS, HUISHNISH, ISLAND OF SOUTH UIST.

PLATE XII.

RESTORED ELEVATION OF ANCIENT BOTH AND SECTION OF HYPOGEUM OR TIGH LAIR, ON THE LINE a, k, NEAR MOL A DEAS, HUISHNISH, SOUTH UIST.

"These piers were about 4 feet high, 4 feet to 6 feet long, and 1½ foot to 2 feet broad; and there was a passage of from 1 foot to 2 feet in width between the wall and them."

"On a small, flattish terrace, where the hill sloped steeply, an area had been cleared by digging away the bank, so that the wall of the house, for nearly half its circumference, was the side of the hill, faced with stone.... The hypogeum or subterranean gallery is on a level with the floor, pierced towards the hill, and is entered by a very small doorway [marked d on Ground Plan, Plate XI.].... It is but 18 inches high and 2 feet broad, so that a very stout or large man could not get in." (Op. cit., pp. 166, 167.)

Plates XI. and XII.—"Both" and Underground Gallery at Huishnish, South Uist.

(From Plates XXXIV. and XXXV. of Vol. VII. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)

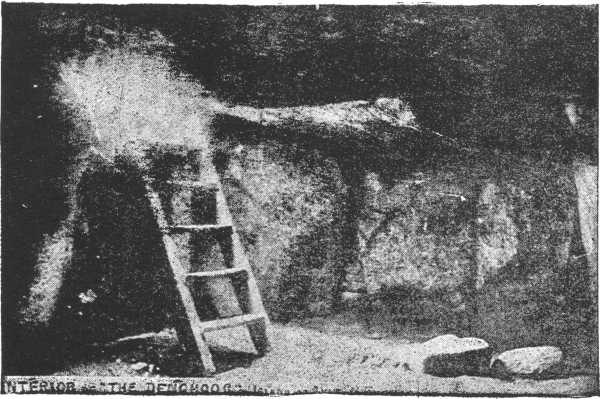

"An ancient dwelling, semi-subterranean, exists at Nisibost, Harris [and is described in vol. iii. of the Proceedings, p. 140].... A still finer example exists near to Meall na h-Uamh, in South Uist.... The bo'h, or Pict's house, as it would be called in the Orkneys—but the name is unknown in the Long Island—that I am about to describe lies less than half a mile above the shepherd's house; but so little curiosity had that individual that he was entirely unacquainted with it; and I believe it would never have been found by us but for a little terrier (in its etymological sense, of course) of a daughter. The child was only acquainted with the two here drawn [of which the other—viz., Uamh Sgalabhad, is here reproduced as Plate I., frontispiece]; but there may be many more waiting the researches of the zealous antiquary." (Captain Thomas, op. cit., p. 165.)

"The drawing is from a photograph of the entrance, which is 2 feet 10 inches high and 1½ foot broad. The sea flows up to it at high tides."

Plate XIII.—Underground Gallery at Paible, Taransay, Harris.

(From Plate XXIX. of Vol. VII. of Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, First Series.)