|

|

The story of Elaine

The Lily Maid of Astolat

From the Arthurian legends

Collected by Sir Thomas Malory And Later Writers

Illustrations by Gustave Doré

The Arthurian Legends originated in, and refer to, a period of contest, when the great English nation was assuming a definite form, and are necessarily vague and mythical, but so heroic in their nature, so abundant in the materials of romance, that the early chroniclers delighted to adopt and amplify them.

The rough ballads in favour with the less educated classes repeated in another form the sentiment of the more elegant poems; and the Arthurian Legends were embodied in the imaginative life of the nation. Modern writers have found in them the basis of poems which are among the choice treasures of English literature: and the most imaginative of living artists has illustrated them with marvellous power.

The versions of the Legends now announced are collected from the traditions preserved by Welsh bards and British chroniclers, the Norman romancists, and the poets of Italy, the collections of stories so elaborately made in the fifteenth century by Sir Thomas Malory, and the results of the investigations into Breton legends by the accomplished French writer, Villemarque.

The versions of the Arthunan Legends comprised in this Series art bj a writer who has earnestly studied the antique poems and stories, and vho has endeavoured to preserve in the prose narra'ive something of the grace and pathos, the spirit and picturesqueness, which distinguish the old chronicles and poetic romances.

Preface

TENDEREST and most pathetic of all the legends which cluster around the central figure of Arthur is the story of the maiden dying of unrequited love for the splendid Lancelot. Told with unaffected simplicity in the pages of Sir Thomas Malory, it is a legend ranking with the highest efforts of more ambitious genius. That the graceful story, so beautiful and touching, should so long have been overlooked by the genius of more modern writers is surprising ; but in our times it has assumed a form in which the delicate gradations of the young girl's love and innocence are subtly delineated. In the older form of the legend the picture is presented in a framework of chivalrous adventure; and, as rendering the story more varied and complete in its accessories, the compiler of the following version has preserved the characteristics of the older writers. In the Illustrations Gustave Dore has shown how fully he has appreciated the sentiment and pathos of the legend, and some of them are acknowledged to be among the masterpieces of his genius.

G. R. E.

TWO Elaines appear in the old collections of Arthurian legends. One, the daughter of King Pelles, was more like the "wily Vivien" than the "Lily Maid of Astolat," and we willingly dismiss her from our minds, only noting that she took part in a conspiracy to deceive Sir Lancelot, who, in consequence, went nearly mad for two years, and wandered away from the Court; and Guinevere, agitated by the contending passions of jealousy and loving anxiety, banished Elaine (who as the result of the deception she had practised, became the mother of Sir Galahad) from her presence. Elaine, angry with the Queen, persuaded Sir Bors, the nephew of Sir Lancelot, that Guinevere was the cause of that good knight's absence. Sir Bors went to the Queen to reproach her, and we quote a few lines from Sir Thomas Malory's book, on account of the quaint manner in which the interview is related:

" Sir Bors rode straight unto Queene Guenever. And when she saw Sir Bors, shee began to weepe as if shee had beene wood [demented]. 'Fie upon your weeping!' said Sir Bors, 'for ye weepe never but when there is no boote. Alas!' said Sir Bors, 'that ever Sir Launcelot's kinne saw you, for now have ye lost the best Knight of all our blood, and he that was the leader of us all, and our succour; and I dare well say and make it good, that all Kings, Christian nor heathen, may not find such a knight, for to speake of his nobleness and curtesie with his beauty and gentlenesse. Alas! what shall we doe that be of his blood.' 'Alas!' said Sir Ector de Maris. 'Alas!' said Sir Lionell."

The other Elaine, the daughter of the Lord of Astolat, is the most charming figure presented to us in the legends. She is almost Shakesperian in frankness, devotion, and over-mastering love, a sister in poetic literature to Imogen and Ophelia. Tennyson has rescued this gem from the antique setting in which it was seen by few, and in the framework of his pathetic Idyll it shines like a star.

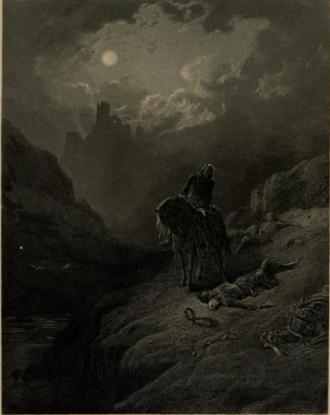

King Arthur discovering the skeletons of the brothers

"And from the skull the crown

Roll'd into light, and turning on its rims

Fled like a glittering rivulet to the tarn."

TENNYSON'S "ELAINE.

The modern poet has adhered very closely to the incidents of the narrative in Sir Thomas Malory's book, the principal departure being in the introductory part, descriptive of the preparations for a great tournament in which many of the bravest knights were to take part. Malory says that King Arthur arranged a tournament at "Camelot, that is Winchester," and announced that he and the King of Scotland would joust against all that would come against them. Who this King of Scotland was, we know not the shadowy figures of the legends will not bear scrutiny; but the challenge had the effect of arousing the martial ambition of many warriors of rank and renown. "There came thether the King of Northgalis, the King Anguish of Ireland, and the King with the hundred knights, and Sir Galahad the haut Prince, and the King of Northumberland, and many other noble dukes and earles of divers countreys."

Tennyson gives another reason for the holding of this "joyous passage of arms." When Arthur, he says, was a wandering knight, before his election to the kingly dignity, in one of his journeys in search of adventure, he reached a dark glen, with gray boulders and a black tarn, or pool, respecting which a fearful legend was told. In some older time, two brothers, whose names even were forgotten, but one of them was a king, had fought together, and each had slain the other. The skeletons remained, and on the skull of the dead king was a golden circlet in which nine diamonds of rare beauty flashed. Riding through the glen, in the "misty moonshine," Arthur trod unawares on the skeleton, and the crown, detached from the skull, rolled down the steep towards the little tarn. Seeing the gleam of the jewels, Arthur ran quickly after the circlet, caught it, and set it on his own head, for he knew in his heart that he would come to be a king.

When he was a great king, surrounded by a brilliant Court, and the centre of that glorious circle of knighthood, he showed the diamonds, and offered them as prizes, one each year, to be contended for at tournaments, so as to encourage valour and martial skill, and prove who were the stoutest champions to fight against the heathen invaders of the land. Previous to the tournament which opens the story of Elaine, eight of these "diamond jousts" had been held, and each year Lancelot had been the victor. Now the largest diamond, that which had been in the centre of the crown, was to be competed for, and Lancelot hoped to win it, and then he would present them all to Guinevere, "a boon worth half her realm."

When the time came for the tournament to be held, the Queen told Arthur that she was unwell, and therefore could not be present. "I am sorry," said the King," for you will miss seeing the great deeds of Lancelot, and I know you love to see his prowess in the lists." Lancelot was at Arthur's side when he spoke, and the Queen looked on with an expression which he took to mean, "Stay with me." Infatuated as he was with her beauty, he was ready to sacrifice even knightly honour at her slightest wish; and although he had so ardently desired to win the last diamond, and so complete the gift he had intended to offer her, he renounced even that. A ready falsehood rose to his lips; and he told the King that as he was still suffering from the wound received from Sir Mador, when he appeared as the Queen's champion, he intended to take no part in the jousting, but would leave the splendid prize to be won by the valour of another knight.

Perhaps a slight suspicion for a moment troubled the King, for he glanced keenly at the Queen and the knight; but he was of too noble a nature to believe readily in ill, and went his way.

When he had departed, the Queen blamed Sir Lancelot for his conduct. He had mistaken her wishes; half the knights were their enemies, and would be only too ready to say that they were taking advantage of the absence of the over-trusting King to enjoy each other's company.

Lancelot was greatly vexed that he had been so misled; and replied with some bitterness, " You are wise and cautious indeed, now! When we first loved, you cared nothing what any might say. I can well silence any knights who dare to speak too freely of us. Now my admiration of you is well known, and without offence made the theme of minstrels' song, which links together the names of Lancelot, the most renowned of knights, and Guinevere, the most beautiful of women. In the presence of the great King himself, who smiles as he listens, the knights pledge us at the feast. What can be the reason of your caution now? Has Arthur uttered word of jealousy? or are you weary of my love, and desirous to be more faithful to your faultless lord?"

The Queen smiled scornfully as she repeated the words, "Faultless lord! To me he is all fault who hath no fault at all! I cannot gaze upon the sun in heaven. He never reproached me; he never thought I was untrue, and he cares nothing for me. There must be some imperfection in the man who loves me, and whom I can love. I am only Arthur's by the bond of marriage; in heart I am yours. Obey my wishes, then; go to the tournament; and we shall avoid the scandal of little buzzing gnats, vermin which, contemptible as they are, have yet the power to sting."

"How can I appear at the tournament, after the pretext I have made before a King who is so truthful, and whom nothing would induce to break his word?"

" He is innocent as a child," replied Guinevere, " and knows nothing of the craft which is necessary to rule in the world. Had he been otherwise, he would not have lost me. Listen to me, since I must find wit for you. It is said that the knights who meet you in the lists are unmanned by your great reputation, and less able than they would be if opposed to any other, your name conquering as much as your prowess. Go as an unknown knight; they will then do their best, but you will win by this kiss you will. The King will believe that you disguised yourself for the love of glory, and will admire you the more."

Obedient to the Queen, and not displeased at the chance of winning renown and the great prize of the day, Lancelot departed, and rode by unfrequented ways towards Camelot. After long journeyings over lofty downs, and by by-paths, he discovered that he had mistaken the road, and was at a loss to find his way. At length he hit upon a faint track, "all in loops and links among the dales." Following it, he saw towers, which proved to be those of the castle of Astolat (which the old writers identify with Guildford, but with slight authority). Riding up to the gateway, he sounded the horn which hung there ready for the announcement of visitors, and the summons was answered by an old servant-man, who led him to a chamber, and helped him to disarm, but spake no word, for he was dumb.

When Lancelot left the guest-chamber, he was courteously received by the lord of the castle, Sir Bernard of Astolat, who was accompanied by his two sons, Sir Torre and Sir Lavaine, and his beautiful daughter Elaine, "the lily maid," as she was affectionately named. They were talking and laughing lightly, but ceased when the knight approached, and Sir Bernard stepping forward to meet him, asked by what name he should welcome his guest, who, he was certain, by his knightly bearing, must be one of the most famous of Arthur's knights. Arthur the old lord had seen, but the Knights of the Round Table were unknown to him.

Lancelot approaching the Castle of Astolt

Till as he traced a faintly-shadow'd track,

That all in loops and links among the dales

Ran to the Castle of Astolat, he saw

Fired from the west, far on a hill, the towers.'

TENNYSON'S "ELAINE."

Lancelot replied with a graceful dignity, "I am one of the knights of Arthur's Court, and am well known, but I intend to joust as one unknown in the great Diamond Tournament; and as my shield is known to all there by its device, I pray you lend me one that is blank, or at least emblazoned only with some device not mine. Hereafter I will make my name known to you."

"My eldest son, Sir Torre," answered the old lord, "was hurt in his first tilt, the day he was knighted, and cannot take part in any achievement of arms. His shield is therefore blank, and you can take it. But," he added, laughingly, "my younger son, Sir Lavaine, is so valiant and strong, that he will joust for the diamond, overthrow the best knights, and in an hour's time bring the prize to his sister to wear in her golden hair, and make her thrice as wilful as she is already."

Young Lavaine blushed slightly at this jesting. " My sister dreamed of the diamond," he said to Lancelot, "thought that it was in her hand, but she let it fall into a pool, and it was lost. I told her, merrily, that if I fought for it and won it, and gave it her, she must keep it more safely. That was all a jest, and nothing more. But if my father will give me leave to ride to Camelot, and the noble knight will bear with my company, I will do my best, although I cannot hope to win."

The manly modesty of the young knight pleased Sir Lancelot. " I should be glad to have your friendly guidance across these downs," he said; adding, pleasantly, " and you shall do your best to win the diamond it is large and beautiful and if you win it give it to this maiden."

" A large and beautiful diamond," said plain-spoken Sir Torre, " should be worn only by a Queen; it is not befitting a simple maid."

Elaine flushed a little at what she felt was a disparagement in the presence of the stranger knight; for where yet was a girl, who could but know that she was fair, who would like to admit that any jewel was too good for her?

Ready in courtly speech as with knightly arms, Sir Lancelot bowed to the blushing girl, and said, "If beauty be fitting for beauty, this maid might wear as bright a jewel as there is on earth, without breaking the bond of like to like."

Lancelot relating his adventures

" He spoke, and ceased : the lily maid Elaine,

Won by the mellow voice before she look'd,

Lifted her eyes, and read his lineaments."

TENNYSON'S "ELAINE."

His voice was soft and mellow; his face wore a manly, earnest expression, and though scarred with an old sword cut, and bronzed by exposure, he seemed to the eyes of Elaine the noblest man she had ever seen. From that moment she "loved him with that love which was her doom."

Lancelot followed his host to the banqueting hall, with the unaffected grace which is so different from the artificial courtesy, which scarcely hides half-disdain, sometimes shown on similar occasions by men of smaller mind. Dishes and vintages of the best were served, and minstrels played music, in the fashion of the time, during the feast. The guest was plied with questions about King Arthur and the Round Table. The old host delighted to hear of the splendour of the Court, and young Lavaine eagerly listened to the stories of adventure. Elaine sat quietly, her lustrous and inquiring eyes fixed on the animated countenance of Lancelot, as he spake, conscious of an emotion she had never felt before.

From King and knights, from banquet and tilting, the questions turned towards the Queen Guinevere; and then Lancelot, avoiding an answer, rather abruptly referred to the old dumb serving-man who had attended him on his arrival at the castle; and Sir Bernard told how, ten years before, when the heathen invaders had prepared to attack his house, the faithful retainer became aware of their design, and gave his master warning. The Baron, thus timely apprised, with his two sons and little daughter, took refuge in a boatman's hut beside the river, where they remained till Arthur defeated the Saxons on Badon Hill. The servitor, who had saved his master and the children, himself fell into the hands of the ruthless foe, who deprived him of his tongue.

"Doubtless, noble knight, you fought with Arthur then," broke in the eager Lavaine. " Tell us of that fray, for we live far from Court, and have little means of knowing anything about the great King's glorious wars."

Then Lancelot told them how he had been with Arthur in many great battles: had fought all day by the river Glem, and in the four desperate frays by the shore of Douglas, in the forest of Celidon, and in that glorious contest when the king wore the famous cuirass, with the head of the Virgin carved in one large emerald, and set in the centre of silver rays, flashing like quick lightning with every movement of the splendid warrior. He told, too, how he had stood at Arthur's side at Caerleon, when the terrible Saxons, led by Hengist and Horsa, carried so defiantly the banner of the White Horse. At Badon Hill he had seen the King charge at the head of all the Knights of the Round Table, and break the close ranks of the heathen warriors; and when they had been swept down by that terrific onslaught, the King leaped on a heap of the slain, spotted with blood from spur to plume, and shouted triumphantly that the victory was gained. No greater leader was there than Arthur; he appeared to be inspired when fighting against the heathen, though at home he was mild, and exerted himself little in tournaments, where sometimes one of the knights would unhorse him, and then he would only laugh, and say his opponent was the better man.

Elaine listened, thinking that, great as Arthur might be, surely the knight who was speaking must be more valiant. He passed from warlike talk to pleasantry; and there was a dignity even in his mirth. At times the quick, watching eyes of the already love- stricken maid detected a shade of melancholy pass across his features, but when he addressed her, there was a kindly tenderness of manner which she readily believed indicated the nature of the man.

"That night," says the old chronicler, " hee had merry rest and great cheere, for ever the faire damosell Elaine was about Sir Launcelot all the while that she might be suffered."

The fair Elaine slept little; and she dreamed of Lancelot, who seemed in the stillness of the night to be speaking of noble acts and thoughts. She rose early, and slipped down the long tower stairs, to bid farewell to her brother Lavaine, she said to herself; and if there was another she wished to see once more, she strove to hide the secret in her maiden heart. She heard Sir Lancelot, in the courtyard, asking for his shield, saw him smooth the shoulder of his noble horse, and half envied the caress. She modestly stepped forward, and when Lancelot turned his eyes on her, standing half bashfully and half boldly in the innocent confidence of young maidenhood, he felt a reverence for her beauty. He greeted her courteously; and she, yielding to an impulse, which made her face flush and heart beat, said, " Fair, Sir, unknown by name, but I well believe among the noblest, will you wear my favour at the tournament?"

"I never yet have worn a lady's favour in the lists," replied the Knight, " and that all the Court knows, and therefore, dear lady, will not now."

Woman's quick wit and that wit is always brightest when it runs with inclination supplied a ready reason why the Knight should now do what he had never hitherto done. "If it is so well known that you never wear a lady's favour, the more reason why you should wear one now, when you wish to be unknown."

Lancelot hesitated a moment, and then smilingly admitted the force of her argument. Her youth and pretty playful manner led him to regard her as a child, and he told her laughingly to fetch the favour and he would wear it. She ran for it eagerly, and brought him a red sleeve bordered with pearls, which he wound round his helmet, telling her he had not done so much before for any maiden. She blushed with pleasure, and then turned pale, conscious of her boldness. Lavaine brought Sir Torre's unblazoned shield, and then Lancelot asked Elaine to do him the grace of keeping his shield till he returned.

"It is a grace to me," replied the girl, "and the second to-day. Now," she added with a pretty laugh, "I am your squire."

Her brother Lavaine kissed her affectionately, joking with her about her paleness, which was replaced by another flush, when she saw Lancelot's eyes fixed on her, with an expression of mingled kindliness and amusement. He kissed his hand to her, and then with Lavaine at his side rode away. Elaine paused a moment, and then stepped swiftly to the gate, and stood resting on the shield, watching the departing figures " her light hair blown about the serious face, yet rosy-kindled with her brother's kiss," as Tennyson beautifully describes her and then climbed the steep stairs to the tower, taking with her the shield, and "so lived in fantasy."

She placed the shield in her chamber, in such a position that the earliest ray of morning sunshine should gleam on it, and so awake her with the light. That was her first fancy; then she thought it would be soiled or rusted, if left uncovered, and she made a case of silk, embroidered with the devices which the shield itself bore, adding a border of flowers and birds of her own design. Every day she stole away from her father and her household duties, to pass a short time in gazing at her treasure, taking off the embroidered coverlet, and trying to discover the meaning of the emblazoned arms. She invented a little story of high achievement for every scratch and dent on the surface. This mark is fresh, how came it? That is of older time, perhaps the blow was dealt at Caerlyle, or Caerleon, or Camelot. What a stroke must it have been to cause this deep dent! and what a mark of a spear thrust is there! Surely he would have been killed if God had not broken the strong lance, and so saved the noble knight!

Lancelot bids adieu to Elaine

" He look'd, and more amazed

Than if seven men had set upon him, saw

The maiden standing in the dewy light."

TENNYSON'S "ELAINE."

" So she lived in fantasy."

Sir Thomas Malory's chronicler says that King Arthur was staying at the great castle of Astolat not the tower belonging to Sir Bernard, Elaine's father and saw Lancelot, whom he recognized. He guessed that he intended to joust in disguise, and would not reveal the secret to his knights; but when the day for jousting came, he kept near him his beloved nephew Sir Gawaine, and would not allow him to take part in the mimic fray for he feared he might be hurt by Lancelot. The modern poet takes no notice of the incident; and indeed the scene has more dramatic force if we suppose that Arthur believed it was a strange knight who exhibited such remarkable prowess.

Sir Lancelot and Sir Lavaine had rested for a night in the cave of a hermit, who had once been a knight, but who had lived in solitude for forty years; and when they left in the morning, Lancelot told his companion who he was, but enjoined secrecy. "You ride with Lancelot of the Lake." Lavaine had heard of Lancelot, the greatest of all the Knights of the Round Table, and perhaps had heard the legend that the fairy Lady of the Lake had stolen him when an infant from his mother, and was for a moment abashed to find himself in the company of such a hero. Then he gave way to the natural enthusiasm of youth. "Now that I have seen the great Lancelot, there is but one more whom I desire to see, and that is Arthur, 'the dread Pendragon, Britain's king of kings.' I would press forward to see him, even if I knew I should be struck blind the next minute, for, at least, I could say I had seen him."

When they reached the lists, Lavaine gazed with delight on the fair scene before him. Half round the meadow was a gallery filled with a brilliant company, and on a lofty seat, the arms of which were moulded in the form of dragons, sat Arthur the King, clad in a crimson robe, and with a dragon crest on his helmet. Over his head, set in a costly canopy, was the great diamond for which the knights were to contend.

Lancelot allowed his young companion to gaze for a brief time in silence and with reverential awe at Arthur, and then said, "You have called me great. True I have a firm seat and a good lance, but there are youths there who will achieve as much as I have done, or even more. I have no greatness, unless there be a touch of greatness in knowing my own imperfection. There," he added, turning his eyes to the King, " there is the man."

There was soon enough to attract the attention of Lavaine in the movements of the kings, princes, and knights who entered the meadow prepared to take part in the jousting. A few moments before he had said that if he could see Arthur he would wish to see no more; but, no doubt, he would have been grieved enough not to have seen the fair pageant on which he now looked.

We will allow the chronicler to describe the beginning of the jousting, for the old writers took a peculiar pleasure in writing of such gallant encounters, the very names of the knightly combatants appearing to ring like clashing arms:

"Some of the kings, as King Anguish of Ireland and the King of Scotland, were that time turned upon King Arthur's side. And then upon the other part was the King of Northgalis, and the King with the Hundred Knights, and the King of Northumberland, and Sir Galahalt, the haul [haughty] prince. But these three kings and this one duke were passing weake to hold against King Arthur's part, for with -them were the most noble knights of the world. So then they withdrew them either partie from other, and every man made him ready in his best manner to doe what he might The King with the Hundred Knights smote downe the King of Scotland, and also the King with the Hundred Knights smote downe King Anguish of Ireland, then Sir Palomides, that was on King Arthur's part, encountered with Sir Galahalt, and either of them smote downe other, and either partie helpe their lords on horseback againe. So there began a strong assaile on both parties. And then there came in Sir Brandiles, Sir Sagramore le Desirous, Sir Dodinas le Savage, Sir Kay the Seneschal, Sir Griflet le rise de Dieu, Sir Mordred, Sir Meliot de Lagris. Sir Ozanna le Cuer-hardy, Sir Safire, Sir Epinogris, and Sir Galleran of Galway. All these were Knights of the Round Table. So these with other more came on together, and beate back the King of Northumberland and the King of Walles."

The last-named King is probably identical with the King of Northgalis before-mentioned; but it would be vain indeed to expect exactness in such a matter.

Lancelot watched the fray silently until he saw that one side was greatly the weaker; and then, followed bravely by young Lavaine, he dashed into the fight, levelling his lance against the stronger party. Tennyson says, "Little need to speak of Lancelot in his glory; king, duke, earl, count, baron, whom he smote he overthrew." The old chronicler, who loved to be minute, gives ampler detail of the great knight's tremendous onslaught.

"Sir Launcelot smote down Sir Brandiles, Sir Sagramore, Sir Donidas, Sir Kay, and Sir Griflet, and all this he did with one speare. And Sir Lavaine smote down Sir Lucas [Lukyn], the butler, and Sir Bediver. And then Sir Launcelot got another great speare, and then hee smote down Sir Agravaine, Sir Galeris, Sir Mordred, and Sir Meliot de Logris; and Sir Lavaine smote down Ozanna le Cuer-hardy. And then Sir Launcelot drew out his sword, and there hee smote on the right hand and on the left hand, and by great force hee unhorsed Sir Safire, Sir Epinogros, and Sir Galteran; and the Knights of the Round Table withdrew them backe, after they had gotten their horses, as well they might."

"Who is this valorous knight?" exclaimed Sir Gawaine. "From his noble riding and the mighty blows he deals, I should think he is Sir Lancelot; but it cannot be, for he had a red sleeve on his helmet, and Lancelot would never wear the favour of any lady."

Lancelot's own relatives were so jealous of his fame, that they were enraged to see a stranger exhibit valour and skill in arms which outdid anything that he had achieved, and nine of them resolved to attempt to retrieve the fortunes of the day. Tennyson describes the fight with great vigour; but probably the prose of the old writer quoted by Malory reproduces the scene with even more vividness:

" Then Sir Bors, Sir Ector de Maris, and Sir Lionell called unto them the Knights of the blood, as Sir Blamore de Ganis, Sir Bleoboris, Sir Aliduke, Sir Galihad, Sir Galihodin, and Sir Bellangere le Beuse. So these nine knights of Sir Lancelot's kinne thrust in mightely, for they were all noble knights; and they, of great hate and despite that they had to him, thought to rebuke that noble knight Sir Launcelot and Sir Lavaine, for they knew them not. And so they came hurtling together, and smote downe many knights of Northgalis and of Northumberland. And when Sir Launcelot saw them fare so, hee gat a speare in his hand, and hee encountered with them all at once; Sir Bors, Sir Ector de Maris, and Sir Lionell, smote him all at once with their speares. And with force of themselfe they smote Sir Launcelot's horse unto the ground; and by misfortune Sir Bors smote Sir Launcelot through the shield into the side, and the speare brake, and the head abode still in the side. When Sir Lavaine saw his maister lie upon the ground, he ranne to the King of Scotland, and smote him to the ground, and by great force hee tooke his horse and brought him to Sir Launcelot, and mauger [notwithstanding] them all hee made him to mount upon that horse. And then Sir Launcelot gat him a great speare in his hand, and then he smote Sir Bors both horse and man to the ground; and in the same wise he served Sir Ector and Sir Lionell; and Sir Lavaine smote down Sir Blamore de Ganis. And then Sir Launcelot began to draw his sword, for he felt himselfe so sore hurt, that he went there to have had his death; and then hee smote Sir Bleoboris such a buffet upon the helme that hee fell down to the ground in a sownd; and in the same wise hee served Sir Aliduke and Sir Galihad. And Sir Lavaine smote downe Sir Bellangere, that was the sonne of Sir Alisaunder Lorphelin. And by that time Sir Bors was horsed; and then hee came with Sir Ector and Sir Lionell, and they three smote with their swords upon Sir Launcelot's helmet; and when hee felt these buffets, and his wound that was so grievous, then hee thought to doe what hee might whiles hee might endure: and then hee gave Sir Bors such a buffet that hee made him to bow his head passing low; and therewith all hee rased off his helme, and might have slaine him, and so pulled him downe. And in the same manner of wise he served Sir Ector and Sir Lionel!, for he might have slain them. But when he saw their visages his heart might not serve him thereto, but left them there lying. And then after hee hurled in among the thickest presse of them all, and did there miraculous deeds of armes that ever any man saw or heard speake of. And alway the good knight Sir Lavaine, was with him; and there Sir Launcelot with the sword smote and pulled downe moe than thirty knights, and the most part were of the Round Table. And Sir Lavaine did well that day, for hee smote downe ten knights of the Round Table."

Evidently there was fierce fighting, and the chivalric Knights of the Round Table had no scruples on the score of fair play to prevent several of them attacking one at the same time. Here probably Sir Walter Scott found the germ of the incident of the tour- nament at Ashby-de-la-Zouch, when Ivanhoe, having so greatly distinguished himself, was set upon by the gigantic Front-de-Bceuf, the Saxon Athelstane, and the Templar, who rode at him together, but were scattered by the Black Knight, who came so vigorously to the rescue.

There could be no doubt as to who was victor and entitled to the prize; but there was considerable curiosity to know who the knight with the red sleeve on his helm could be. Lancelot only, it was thought, could have achieved such exploits, and Lancelot it could not be, for he had always refused to wear any lady's favour in the lists; and the blank shield afforded no clue to the mystery.

"Advance, Sir Knight, and take the prize," cried the heralds. "Advance, Sir Knight of the Red Sieve, and receive the diamond."

A number of the knights whom he had helped so well, led by the King of Northumberland, the King with a Hundred Knights, and Sir Galahalt, the haut prince, rode up to him, and asked him to come with them to receive the honour he had so valiantly won.

"My prize is death," replied Sir Lancelot. "I pray you that I may depart and not follow me, for I am grievously hurt. Honour I cannot accept now, for I would rather rest than be lord of the whole world."

Assisted by Sir Lavaine, he quitted the meadow where the lists were held, and, almost fainting from the pain of the wound, he reached a little wood about a mile distant, then he almost fell from his horse, and sank upon the ground. " Draw the lance head," he said to Lavaine; "as you love me, draw it out." "I shall kill you, if I do!" replied the young knight, trembling with anxiety. "I am already dying with the pain," said Lancelot, scarcely able to utter the words, so great was the agony he endured. Lavaine then, with a great effort of strength, pulled out the fragment of the weapon, and Lancelot, with a shriek and groan, fell senseless on the ground, the blood pouring from his side.

They were not far from the cave where dwelt the hermit knight, and Lavaine obtained his help. Between them they raised the wounded Lancelot from the ground, and then the hermit, who was "a full noble surgeon and right good leche," staunched the blood and dressed the wound.

The popular estimate of hermits is rather shaken by the description given in the old chronicle of this recluse. He had been known as Sir Bawdewine, and although styled a hermit, and living in a cave divided into several chambers, he had servants, and was generously hospitable to visitors, although somewhat punctilious, and desiring to know who they were that required his aid. When summoned by Sir Lavaine, he questioned him about the wounded knight, and asked if he belonged to the Court of King Arthur.

" I know not who he is," replied Lavaine; "but this day he has done marvellous feats of arms against the King's party, and won the prize, defeating all the Knights of the Round Table."

"At one time," said the hermit, "I should have had small love for him for that reason, for I was a Knight of the Round Table in my young days. But I am otherwise disposed now, and will give him all the help I can."

The hermit recognised Lancelot directly he saw him, and having looked at the wound, told him it was not fatal. Then he called two of his servants and they bore the wounded knight into the cave, removed the armour, and lay him on a bed. A draught of good wine was administered; for the good recluse was not one of those who had nothing in their caves but " a scrip with herbs and fruits supplied, and water from the spring," but appreciated the virtues developed by good living. " n those daies," says the old writer, " it was not the guise of hermites as it now is in these daies, for there were no hermites in those days, but that they had beene men of worship and of prowesse, and those hermites held great housholds and refreshed people that were in distress."

After Lancelot had left the field, the kings and knights who had jousted went together to Arthur, and told him that the Knight of the Red Sleeve, who had borne him so bravely and won the prize, was wounded seemingly unto death, and they knew not where he was.

"He is a great knight," said the King; " indeed he seemed to me another Lancelot. He must be well cared for. Go you, Sir Gawain, search for him; wounded and wearied as he is, he cannot be far away. Take with you the diamond he has won, and when he is found give it to him, and then return and tell us who he is and how he fares."

Gawain, with a squire in attendance, rode not very willingly on the quest, for by so doing he missed the banquet. After riding about for several hours, he returned unsuccessful. At the banquet Arthur was depressed in mind. The thought haunted him that the stranger knight was no other than Lancelot, who, although he had made his old wound a pretext for not taking part in the jousting, had fought there, added wound to wound, and perhaps had only ridden away to die. Two days afterwards he returned to the Queen, and she, after embracing him lovingly, asked for Lancelot, and if he had not won the prize. When the King told her that the diamond was won by an unknown knight, she answered quickly, "Why, that was he!" and told Arthur how Lancelot had determined to go disguised to the tournament, and that the old wound was but a pretext for not accompanying the King.

Arthur showed displeasure when he heard this. " Better would it have been," he said, " had he trusted me, his King and old familiar friend, or he had trusted you. I should have laughed at the pretence that any of my knights were so overcome by his fame that they were unable to do their best against him in the field. Now there is little cause for laughter, for he went from the field sorely wounded. Yet there is some good news too, for it seems that Lancelot is no longer lonely for need of love, for he wore around his helm a scarlet sleeve, embroidered with pearls, doubtless the gift of some fair maiden."

Guinevere almost choked with suppressed emotion. Hurrying to her chamber, she flung herself on the couch, and, with passionate sobs, denounced Lancelot as a traitor to her love. A wild burst of tears relieved her agony, and then she "rose again, and moved about her palace proud and pale."

The King and Court returned to London; and Gawaine, who still kept the diamond, and was charged to continue to search, found himself late in the evening at Astolat, and asked for rest and refreshment. Good old Sir Bernard and the fair Elaine attended on him, and both were eager to hear news of the great doings at Camelot. "Who won the prize?" they asked almost together; the father because he loved to hear of acts of valour, and the daughter because the image of the glorious knight was treasured in her heart; and she knew by the instinct of her great love, that he, and none but he, must have been the victor.

"There were two strange knights, with blank shields," replied Sir Gawaine, " and one of them wearing a red sleeve on his helm was the most valiant knight I ever saw; for, believe me, he smote down forty Knights of the Round Table; and the other knight showed great valour."

Elaine could not restrain her joy. "I knew it," she exclaimed; "I knew the knight with the red sleeve would be the victor." Doubtless she would have been well pleased to know that her brother had also distinguished himself, but her heart was filled with Lancelot. The colour fled from, her cheek, however, when Gawaine went on to relate that the brave knight was badly wounded in the side by a lance thrust, and that he had left the field seemingly in a dying condition. The young girl almost fainted, and placed her hand quickly on her own side, as if she too felt the agony caused by the wound; shrewd Gawaine at once guessing the secret of her love. He went on to tell how he was charged by King Arthur to find the wounded knight, and if he was alive, give such aid as he could, and place in his hands the diamond he had won.

The Baron, not so ready as the younger and more astute Gawaine to notice Elaine's emotion, said bluntly, " Ride no farther on the quest, at least at present. The good knight was here, and left his shield, which he will surely either fetch or send for; besides, my son is with him, so we must needs have speedy news of him."

Gawaine, with the courtesy he so well knew how to assume, agreed to tarry a while at the castle; not unwillingly indeed, for the rare beauty of Elaine attracted him, and he resolved to practise upon her simple and untutored nature the arts of gallantry which had found him favour with the lighter ladies of the Court. His glittering wit, ready conversation, complimentary conceits of speech, and snatches of love songs, made no impression on the Lily Maid. " You forget your quest," she said, " and slight your King by not asking to see the shield the good knight left, by which you might be able to know who he is."

The shield was fetched. Elaine with tender reverence removed the silken cover she had made, and Gawaine saw the well-known bearings of Lancelot's azure lions crowned with gold. " The King was right!" he exclaimed; " it was Lancelot!"

Elaine said quickly, excitement bringing the roses to her cheek again, " I, too, was right. I dreamed my knight was the greatest of all the knights."

Gawaine bent his head toward her, and said, " Fair maid, pardon me, but is that good knight your love?"

She answered innocently, " I scarce know what true love is; but if I love not him, I can never love any."

Gawaine thought, " He wore her sleeve, perhaps he may have wearied of the Queen, and loves this little maid. If so, I will not attempt to cross the path of the mighty Lancelot." Turning to Elaine, he addressed with courtly grace, " I think, fair damsel, that you know where your great knight is hidden. I will leave the diamond with you. If you love him, it will be sweet for you to give it; if he loves you, it will be sweet for him to take it from your hand. Farewell! We may meet at Court hereafter." He gave her the diamond, lightly kissed her hand, then leaped on his horse, and rode away, carolling a love ballad as he went.

Arthur was angry that Gawaine had so easily renounced the quest for Lancelot, and that he had given the diamond to Elaine. It was speedily known throughout the Court that it was Lancelot who had won the prize; and the story of Elaine's love was soon known too, for Gawaine told freely what he had heard, and was full of praises of the beauty of the Lily Maid of Astolat. The gossip of the Court ran in no other channels. Even at the banquets the knights toasted " Lancelot and the Lily Maid." The Queen preserved an outward show of calm, tranquilly remarking she was sorry so great a knight as Lancelot had stooped so low; but jealousy was in her heart, though none saw outward sign of the subdued, but fierce passion which possessed her.

While this was passing at Camelot, the Lily Maid was anxiously thinking at Astolat how she could find and aid the missing wounded knight who was so dear to her. She felt a maidenly diffidence at first in speaking to her father, and hesitated to tell him how she loved Lancelot, but asked him to let her go to seek her brother, "dear Lavaine." Sir Bernard, shrewder than she thought, had not failed to observe the effect the visit of Lancelot had produced on the mind of his young daughter, and answered with a smile, " You need not be so anxious about Lavaine; wait a little time, and we shall hear of him; and," he added after a moment's pause, " of the other knight too."

Elaine could no longer conceal what was uppermost in her mind. "That other knight I must seek and find. If I do not give him the diamond he has won, I shall faithless as that proud Prince who left the task of seeking Sir Lancelot to me. Dear father, let me go. In my dreams I see the face of that noble knight, wan and pale from sickness, and wanting the tendence which woman best can give. The more gentle-born maidens are, the more are they bound to help in sickness brave knights who have won their favour."

The old man could not resist the pleading tones of his young daughter who sat on his knee and laid her cheek so lovingly against his; and he was, besides, anxious about the fate of the great knight. " You should give the diamond," he said; " and as your heart is set upon the matter, and you are so wilful, you must go."

"Being so wilful, I must go," repeated Elaine to herself, and there seemed to be a faint echo, which changed the words to " Being so wilful, I must die!" The despondency was but for a moment, and she courageously added, "What matter if I die, so that he lives?" Her kind, but dull and moody brother, Sir Torre, went with her as a guide and protector, and together they rode over the downs to Camelot. Outside the city gates, she saw her brother, exercising his horse; and riding swiftly up to him, cried, " Lavaine, how fares my lord Sir Lancelot?" Her brother was surprised at her appearance, and still more surprised that she should know his friend's name, which he thought had been concealed from all but himself. She told him what had happened since his departure: the visit of Sir Gawaine, his recognition of the shield of Lancelot, and his entrusting the diamond to her care.

Elaine on her Road to the Cave of Lancelot

" Then rose Elaine and glided thro' the fields,

So day by day she past

In either twilight, ghostlike to and fro Gliding."

TENNYSON'S "ELAINE."

Having conducted her so far, Sir Torre left her with Lavaine, and went into the city, where some distant relations of the family dwelt. Elaine accompanied her younger brother to the cave, and there saw, with a secret pleasure throbbing in her heart, the casque of Lancelot, with her embroidered sleeve still twined around it, but cut and hacked by the heavy blows, and half the pearls shorn away. In an inner cell lay Lancelot sleeping, but dreaming, it would seem, of combat, for there were convulsive movements of the sinewy hands and arms as if he were wrestling with a foe. His face was haggard and pale, and his figure gaunt. The loving girl could not repress a little outburst of grief when she saw the wasted form of the once splendid knight, and the cry roused him from his sleep. (The old writer but he has generally a liking for strong effects says she fell on the ground in a swoon, and lay there a great while.) When she saw his eyes open and his head turn towards her, she knelt down by the side of the couch, and placed the diamond in his open hand, saying, " This is your prize, the diamond, sent you by the King." The eyes of the sick knight brightened, and a gleam of pleasure for a moment lighted up his wan face. " Is he pleased that I am here?" the girl asked herself. In a low voice, fearing to excite him, she gently told him of Gawaine's quest, and that she had undertaken to find him and give him the prize. As she knelt, her face was near his, and he kissed her as he thanked her; not as a lover would kiss the maiden dear to his heart, but, as the poet expresses it, "as we kiss the child who does the task assigned."

Now that her mission was so far discharged, the tension of her mind relaxed, and she sank on the floor, almost fainting. The kiss was a token of thanks, not of the love she so desired. Lancelot spoke kindly, " You are fatigued and need rest."

She could not, if she would, have controlled the reply which rose to her lips. "I am at rest when near you, fair lord, and need naught else;" and the quick blood rose to her face, showing a consciousness that she impulsively uttered what she should have concealed.

Lancelot's large black eyes, appearing larger and more lustrous, his face was so pale and thin, rested on her blushing face, which revealed to him a love he had not sought and could not return, for there was but one woman whose love and that was unlawful love he desired. He pitied her; but to avoid speech, for he was perplexed in mind and weak in body, he turned his face and feigned sleep till real sleep came.

Elaine, seeing that he slept, left the cave and crossed the meadows to the city, where her kinsfolk, prepared by Torre for her appearance, welcomed her, and with them she passed the night. At dawn she "passed down through the dim rich city to the fields, thence to the cave." Day after day she watched by the couch, and ofttimes too at night. The fever touched his brain; he talked wildly, and sometimes even uncour- teously, to the maiden who nursed him as tenderly as a mother nurses a sick child; for " her deep love upbore her." The hermit, well skilled in all the healing sciences of his time, saw how little his skill could effect, compared with the womanly tenderness and attentive watching of Elaine.

When the fever abated, and Lancelot again recognised the sweet face of the girl, and knew how tenderly she nursed him, he grew to love her, but only as he might love a dear young sister. He listened for her coming step, spoke to her affectionately, called her his friend, and "sweet Elaine," and laid his large thin hand in hers. Had they met before the superb beauty of the Queen had dazed his mind, the young girl's pure trusting love might have made of him another and a better man. But, in the words of Tennyson, words which, in the subtle antithesis, have a Shakesperian form and depth of meaning

"The shackles of an old love straitened him.

His honour rooted in dishonour stood,

And faith unfaithful kept him falsely true."

At times, as he lay watching the slight figure of Elaine moving noiselessly about the cell, as he heard her low musical voice speaking to him so tenderly, as he took from her hands the nourishing food she had prepared, or the cooling draught, he seemed to live a purer, holier life, and he resolved no more to give way to his guilty love. Un- worthy thoughts were, at times, banished in the presence of her loving maidenhood, as evil shapes are forced to fly from the pure light beaming from guardian angels. But as he became stronger, his fiercer passions returned; the shadow of Guinevere seemed to stand between him and Elaine, and if she spoke, he answered curtly and coldly. Elaine had borne all while the fever raged, for she knew that the malady spoke, not the courteous, kindly man; but what this sudden coldness, this abrupt reserve, meant, she could not guess. Tears rose to her eyes, and, earlier than was her custom, she left the cave and crossed the meadows to the city.

"He does not, cannot love me," she kept on repeating to herself. All night long the echo of the words, " Being so very wilful, I must die " the words which had risen to her lips when she left Astolat sounded in her ears, " Must I die?" she asked herself; and no answer could her heart give, but "Him or death!"

With returning strength, Lancelot had a desire to see his kinsman, Sir Bors, and tell him how freely he forgave him the injury he had received. Lavaine went to Camelot, found Sir Bors, and led him to the cave, where the good knight wept bitterly at the sight of his cousin and friend whom he had so sorely wounded. Sir Lancelot comforted him. "Say no more, it was my own fault that I was hurt, for I might have given you warning of my being there. My pride was such that I wished to overcome you every one, and in my pride I was nearly slain."

Sir Bors then told him that the Queen was angry because he had worn the favour on his helmet; and he asked him if the young maiden who was so busy in tending him was the Fair Maid of Astolat. " It is," replied Lancelot, " and I cannot persuade her to leave me."

That remark was not kind, or worthy of the knight, but his mad love for Guinevere perverted his better nature, and he knew he had deeply offended her by wearing Elaine's sleeve.

Sir Bors, a generous and good knight, could not forbear a remonstrance, and said, " Why should you wish her to leave you? She is very fair, of good birth, and modest manners. I would that you could love her, for I see plainly that she loves you."

" I am sorry for it," answered Lancelot curtly; and then they talked of other matters.

Sir Bors remained in the cave until Lancelot felt strong again, and appeared almost like his old self. The old writer says, " Ever the fair maid Elaine did her diligence and labour night and day unto Sir Launcelot, that there was never child more meeker unto the father, nor wife unto her husband, than was that faire maide of Astolat." Sir Bors told Lancelot that there would be another great tournament held at Camelot, and that King Arthur would joust with the King of Northgalis. This news excited in the knight a desire to be present; and taking advantage of the absence of the hermit and Elaine, and with the aid of Sir Bors and Sir Lavaine he armed himself, mounted his horse, which was very fresh after a month's rest, couched his lance, and spurred his steed to the charge, to test his own strength. The exertion was too much; the partly-healed wound reopened, and Lancelot fell fainting to the ground. Elaine came running up, " and when she found Sir Launcelot, cried and wept as she had beene wood [bereft of reason], and then she kissed him, and did what she might to wake him; and then she rebuked her brother and Sir Bors, and called them both false traitours, and why they would take him out of his bed; then she cried and said she would appeale them of his death." The hermit then came to the help of the fainting knight, and stanched the wound. He knew he had a troublesome patient to deal with, and said, " Ah, Sir Launcelot, your heart and your courage will never be done untill your last dale; but yee shall do now by my consaile."

Tennyson does not mention this incident, which exhibits very naturally the deep love and the quick spirit of the young girl, excited by the condition of the man whom she loved so warmly and had nursed so tenderly. The poet relates the return to Astolat of Elaine and her brother Lavaine, with Lancelot, quite recovered from his wound. The love of Elaine grew day by day, not unmmingled with increasing fear that she loved but in vain. When the time came for the knight to depart, he asked her what gift he could offer her as a mark of gratitude for the kindness she had shown him. " Do not fear," he said, "to ask what you will. I am a prince and lord in my own land, and will gladly make the gift well worthy your acceptance."

The colour left her cheek; she had no power to speak for several moments. Then with a sudden effort which made her form tremble with excitement, she said wildly, " I have gone mad; I love you; let me die."

Lancelot spoke kindly, as an elder brother might speak, calling her sister, as he had done in the cave. "What," he asked, "is the meaning of these words?"

She stretched her white arms towards him with a childish innocent gesture, looked at him fondly, her face flushed and her eyes moist with tears. " I only ask your love," she said. "Take me to be your wife."

With all his faults, Lancelot had a greatness and generosity of nature which made him regard with affectionate pity the frank devotion of the maiden, as yet almost a child in years. With a kindly smile he said, " Had I been disposed to wed, my dear Elaine, I should have wedded long since. The time is past now, and I shall never have a wife."

"Then let me go with you," quickly answered Elaine, knowing too little of the world and its evil ways to see the full import of what she asked; " let me be with you, so that I can always see your face, serve you, and follow you through the world."

"Nay," said Lancelot with great firmness, for he knew how impossible it was, con- sistently with manly honour, to grant her request; " to take you at your word would be an ill requital for the kindness of your father and brother, and an injury to yourself, for evil tongues would utter great scandal."

Elaine bent her head, and turned her flushed face from the knight. A moment before she had looked into his eyes with all the earnestness of an intense but innocent love. His words aroused an emotion she had never experienced before, an instinctive knowledge that shame may be allied with love; and her maiden modesty, self-wounded, made her shrink from him whom she loved so truly. She murmured, rather than spoke, dwelling on the words of denial, which she now knew to be wise and noble, but which she also knew were fatal to her : " Not to be near you! not to see your face! Then life has nothing more."

Lancelot was a man of ripe age, and had the wisdom which grows by experience of the world; that not uncommon wisdom by which it is expected others should be ruled but which we are slow to apply to ourselves. He could advise Elaine to control her impulsive, innocent love; but could not make Lancelot fight with and subdue the guilty passion for Queen Guinevere.

" You are very young," he said, kindly; " this is but a youthful fancy, which you will soon forget, or remember only to smile at. The time will, I hope, come when you give your love to a man more suitable in respect of age, and more worthy of you, for I know how true and good you are; and if your chosen knight should not be wealthy, I will give broad lands in my territory beyond the seas, if that will make you happier; and, furthermore, I will be your champion, if needed, in any quarrel, even to the death. This, dear Elaine, I promise, more I cannot."

She listened, with a deadly pallor overspreading her face, and supporting her trembling form by grasping the tree by which she stood. When Lancelot had finished speaking, she said, firmly and clearly, "Of all this I will have nothing;" then the strong effort she had made to control herself relaxed, a loud hysteric cry broke from her, and she fell to the ground.

She was borne by her attendants to her chamber in the tower; and her father who had, unknown to her and Lancelot, heard what had passed, came forward. He recognized the honourable forbearance and kindness of the knight, but asked him to abate somewhat of his courtesy, and by adopting a rougher manner of speech to Elaine, "blunt or break her passion." It was difficult for him, trained to reverential courtesy towards beautiful maidens and really regarding Elaine with an affection such as he might bestow on a loving young sister to follow this counsel; but he resolved not again to see the maiden, or if he saw her, not to have speech with her. With evening came the time for his departure. He sent to Elaine for his shield, and she rose from her couch, took off the silken embroidered covering, and gave the shield to the attendant sent for it. She heard the horse's tramp, and unable to control the desire to take a last look, threw open her casement and gazed eagerly into the courtyard. There was the knight armed and mounted, bearing the shield which had been so treasured, but not bearing on his helmet the embroidered sleeve. Lancelot heard the opening of the casement, and knew that Elaine was there; and she, by the quick instinct of love, knew that he was aware of her presence. He would not look up, but rode slowly away, and Elaine had no token of farewell.

Weary of the world, weary of life, she sat alone in her chamber. The shield was gone, only the silken case she had made remained as a relic of the great Lancelot whose image filled her heart. She loved to fancy that she heard his voice, almost imagined that she saw his stately form and noble face, with the large eyes, by turns so warlike and so tender in expression. Her father, grieving to see her suffering, and her brother who so dearly loved her, came and spoke gentle words of comfort. She answered calmly and affectionately; but when they left her to her own thoughts, it seemed to her that through the darkness came the friendly summons of death; and she thought that she could be well satisfied to fade away as the day faded into gloom, and as the meanings of the wind into silence.

Poetry and music were the natural language of a mind so impulsive and sensitive to beauty as that of Elaine. Her childish fancies had many times been woven into verse, which she warbled to gay or tender tunes, as she played in the fields or nestled on her father's knee. Now her sadness was embodied in a song, which she called the song of love and death; and with a sweet voice she sang it in the solitude of her chamber. Which, she asked herself, is sweeter, Love or Death? I cannot follow Love, and Death must come, and that I follow, for to me now it is more blissful than Love. "Let me die!" she sang, and her voice seemed to have a weird power. The sad melody was heard at dawn above the fierce winds that made the tower rock. There was an old legend of the house, that before the death of one of the family, a spirit was heard singing pitifully and wailing around the castle; and Sir Torre and Sir Lavaine hearing the strange song, thought it was a presage of their sister's death. They summoned their father, and the three hastened to the chamber, where they found Elaine, the bright light of dawn shining on her pale face, and singing the sad song she had made. The old lord bent and kissed her, and then stood gazing on her with profound emotion. The song was ended, and Elaine sank back upon her couch. She took her brothers' hands in hers, and lay silent for some time, looking on their faces. Then she spoke, and told them she had dreamed she was a little child again, and floating, as she so often had done, with them in a boat on the great river. They would not, in those old days, go beyond one jutting point of shore, on which a poplar grew, and she had cried because they would not go further until they reached the palace of the King. In her dream she thought she was alone upon the flood, but at the moment when she said, "Now I shall have my will," she awoke. The wish of her dream was stronger for the awakening; and she asked them to let her go to the broad river, and past the poplar tree, and so on to the King's palace. There she would enter boldly, none would dare to mock at her. She would see Gawaine, who made so many courteous farewells when he left her, and Lancelot, who coldly went away and spoke no word. The King would know her, and know, too, the story of her love: the Queen would pity her; all the Court would welcome her; and she would have rest at last.

Old Sir Bernard thought his daughter was wandering in her mind, and tried to make her understand that she could not, weak and ill as she was, go so far. " Besides," he said, "why do you wish to look again on this proud knight, who evidently holds us all in scorn?"

Sir Torre, who was very fond of his young sister, but whose slow mind was quite incapable of understanding the sensitiveness of her nature, could only think that she felt insulted at Lancelot's silent or as he thought contemptuous departure. He saw how ill she was, and worked himself into a great rage, sobbing while he stormed. " I always disliked him," he exclaimed, " and if I meet with him, I will strike him down, great as he is, and if I can will kill him to avenge the pain he has caused you, and the insult he has passed upon our house."

Elaine checked his speech. "It is not Sir Lancelot's fault," she said, " that he cannot love me, but it is my fault that I could not help loving the man who seems to be the highest and the best."

Her father, who was little acquainted with the composition of such fine natures as hers, and blundered with the kindest intentions, thought if he could show that Lancelot was unworthy, the charm would be dispelled, and Elaine would awake from her delu- sion, and be herself again. With this intent, he repeated ironically her word, "highest." " I know not," he said, " whom you call highest, but I do know what is well known to all about the Court, that Sir Lancelot loves the Queen with a shameful love, and she returns it as shamelessly. If that be high, 'twere hard to say what it is to be low."

" It is a slander, dear father," replied the maid. " The noblest men are made the subject of ignoble talk. It is my glory to have loved so great a man, one so peerless and without a stain. I am not unhappy, and death has no terrors. If you wish me to live, you are mistaken in the course you take, for if I believed what you aver, I should but die the sooner. Dear father, speak no more of Lancelot, but send to me a holy Christian priest that I may confess and be forgiven, and then, forgiven, I can die in peace."

The old chronicler relates this part of the story very pathetically :

"When shee felt that shee must needs passe out of this world, then shee shrove her cleane, and received her Creatour [took the Sacrament], and ever shee complained still upon [spoke piteously about] Sir Launcelot. Then her ghostly father bad her leave such thoughts. Then said she, ' Why should I leave such thoughts? Am I not an earthly woman? and all the while the breath is in my body I may complaine, for my beleeve is that I doe none offence though I love an earthly man, and I take God unto my record I never loved none but Sir Launcelot du Lake, nor never shall, and a cleane maiden I am for him and for all other; and sith it is the suffrance of God that I shall die for the love of so noble a knight, I beseech the high Father of Heaven for to have mercy upon my soule, and that mine innumerable paines which I suffer may be allegiance [mitigation] of part ot my sinnes. For our sweet Saviour Jesu Christ I take thee to record, I was never greater offender against thy lawes but that I loved the noble knight Sir Launcelot out of all measure, and of my selfe, good Lord, I might not withstand the fervent love wherefore I have my death?"

"And then she called her father, Sir Bernard, and her brother, Sir Torre, and heartily she praied her father that her brother might write a letter like as shee would endite it. [Tennyson with great regard to probability, in consideration of the character of the brothers, makes Lavaine to be the writer of the letter.] And so her father graunted her. And when the letter was written word by word like as she had devised, then shee prayed her father that shee might bee watched until shee was dead! ' And while my body is whole, let the letter be put into my right hand, and my hand bound fast with the letter untill that I be cold, and let me be put in a faire bed with all the richest clothes that I have about me, and so let my bed and all my riche clothes be laide with me in a chariot to the next place where as the Thamse is, and there let me be put in a barge, and but one man with me, such as yee trust to stere me thither, and that my barge be covered with black samite over and over. Thus, father, I beseech you let me be done.' So her father graunted her faithfully that all this thing should bee done like as shee had devised."

Tennyson makes her say, " I go in state to Court, to meet the Queen." Poor Elaine! a little touch of human vanity seems to have dwelt in her fair young bosom to the last. She had loved Lancelot, and that love made her equal to the greatest; and Guinevere should see that it was no mean and unworthy damsel whose favour the great knight had worn on his helmet in the lists at Camelot.

The promise given, the Lily Maid seemed happier. Her cheek was less pale, she spoke cheerfully, and her father and brothers hoped that she would rally. For ten days the hope was encouraged, but on the eleventh the signs of speedy death appeared. Her father placed the letter in her hand, and with a smile she died.

" That day there was dole in Astolat," says the poet in terse, old-fashioned phrase.

But at Camelot, whither Lancelot rode, there was rejoicing with some, but dark jealousy in the heart of the Queen. The old writer says :

" When King Arthur wist that Sir Launcelot was come hole and sound, the King made great joy of him, and so did Sir Gawaine and all the Knights of the Round Table, except Sir Agrawaine and Sir Mordred. And also Queene Guinever was wood wroth [wild with anger] with Sir Launcelot, and would by no means speake with him, but estranged her selfe from him; and Sir Launcelot made all the means that hee might to speake with the Queene, but it would not be."

In the modern Idyll, Lancelot does speak with the Queen, and the interview is described with great dramatic power, and concludes with a striking incident. It may be premised that the old story, followed in this respect by Tennyson, removes the Court from Camelot (Winchester) to Westminster, and there the interview between the Queen and Lancelot, and the pathetic last act of the drama, take place. We do not expect much historical accuracy in these old stories, but Walter de Mapes if, as is supposed, he was the originator of the Lancelot series of legends ought to have known better than to have made Westminster a royal residence in Arthurian times. The church which gave the name, " the minster in the west," was built by Sebert, King of the East Saxons, in the seventh century, and there was no palace until about four centuries afterwards. But old legends must not be criticised too minutely, and we must be content with narratives as little like real occurrences as the stupendous castle on a cliff in Gustave Dore's superb drawing representing the barge with the body of Elaine passing down the river, is like anything to be seen at any time in the neighbourhood of Westminster. Poets and artists enjoy the license of the imagination, and it is the gift of genius to find the beautiful everywhere.

At Westminster, then, Lancelot, after his return, asked an audience of Queen Guinevere, that he might lay at her feet the prize he had so hardly won, " the nine- years'-fought-for diamonds." Having won the last and most valuable, he could now complete the offering he had so long desired to make; but he dared not, knowing how he had displeased her by wearing the favour of Elaine, approach her, as of old, without permission. Therefore he sent a message by one of the esquires or pages in attendance on her. The Queen received the request with a calm dignity, and assented with such majesty of demeanour and apparent absence of emotion, that the courtier was awed, and bowed low before her. He knew well the gossip of the Court, and perhaps expected that Guinevere would exhibit some womanly agitation when she received a message from Lancelot. He was deceived; for with great self-command, with firm lips, calm eye, unflushed cheeks, and passionless voice, the Queen gave permission to Lancelot to approach her, and stood as tranquilly as if she were a superb statue, and not a woman whose inmost heart was throbbing with the conflict of love and jealousy. The courtly messenger bowed low, but as he bowed, he saw the Queen's shadow on the wall, which showed that the lace about her bosom trembled. That told the quick-eyed courtier there was no calm within, and he smiled furtively as he quitted her presence.

Guinevere awaited the coming of Lancelot in a chamber the oriel window of which looked upon the broad river. She coldly responded to his obeisance as he entered, and remained silent. He advanced, knelt before her, and in a voice which expressed at once respect and tenderness, offered the jewels. " I had not won them," he said, " if I had not been encouraged and strengthened by my devotion to you, my liege lady. Now that I have won them, may I hope that you will make me happy by wearing them. They will be more beautiful if adorning the roundest arm or the whitest neck on earth. Perchance I sin in speaking of your beauty; but let my admiration have way in words, as tears are granted to grief. I know that there are rumours flying about the Court; but cannot think you will believe them. We have the bond of true love, not the colder bond of marriage, and we should trust each other, knowing how devotedly we love."

The Queen turned away her head while he spoke, thinking to conceal the emotion she felt. In the effort to subdue it, she nervously plucked leaves from the vine which twined around the oriel, and scattered them around her. Then extending one hand, she coldly took the jewels, and without any gesture of thanks, laid them on the table by her side.

Torre and Cabaine bid farewell to the body of Elaine

" So those two brethren from the chariot took

And on the black decks laid her in her bed,

Set in her hand a lily, o'er her hung

The silken case with braided blazonings."

TENNYSON'S "ELAINE.

" Perhaps," she said deliberately, "I am readier to believe than you think me to be. It is true our bond is not that of man and wife, and it is better that it is so, for it can be more easily broken. For years past I have, for your sake, grievously wronged one whom I have known, in my inmost heart, to be a noble man. You say these diamonds are for me. Rich as they are, they would have been of thrice their worth as your gift, if you had not proved yourself unworthy. I will have none of them," she added, her voice rising with the passion that now made her bosom heave and her eyes flash; " give them to your new love. Add these diamonds to her pearls."

Oh! these poor little pearls that decked poor Elaine's red sleeve on Lancelot's helm, how the memory of them rankled in the proud Queen's jealous heart! " Tell her how much more beautiful she is than I. Make her a circlet for her arm, compared to which her Queen's is lean and haggard. Twine a necklace for her fair neck, oh! so fair, as much fairer than mine, as true faith is richer than all the diamonds on earth. Take them to her; they are hers, not mine!"

Suddenly her tone changed, all the fierce elements of her nature were aroused. Hitherto she had borne an aspect of injured dignity, and her words were uttered slowly and in a sarcastic tone. Now she spoke rapidly, and the flush of passion overspread her face. Never had she been more beautiful, if to be terrible is to be beautiful. With a quick gescure she snatched the diamonds from the table, and exclaimed, "They are mine as yet, and she shall never have them!" Then she flung them with all her strength from the open window into the river, and with a quick step passed from the apartment " to weep and wail in secret." She had but played the Queen, but was a very woman in her heart.

Lancelot looked from the window, his eyes fixed on the spot where the diamonds had disappeared. He was weary of love, of life, of all. When he raised his eyes they fell on the barge bearing the dead Elaine!

For her dying request had been complied with. At early morn of the day after she had passed away so gently and lovingly, her brothers had laid her, attired in her richest dress, on a chariot, and went through fields and country ways to the river, where a barge draped with black samite a silken fabric of great richness and beauty- was ready, with the dumb old servitor to steer. They laid her on her bed in the barge, placed in her hand a lily for was not she the Lily Maid of Astolat? hung over her the silken case she had embroidered for the shield of Lancelot, then kissed her cold brow, and with a "Farewell, sweet sister," parted in tears. The simple-hearted, duller Torre wept silently; but Lavaine, quicker in nature, in sensitiveness more like the sister he had lost, gave way to a louder and less controlled grief. The two then slowly returned to the house now so desolate, and to the father so stricken in his age.

The body of Elaine on its way to King Arthur's palace

Steer'd by the dumb went upward with the flood

In her right hand the lily, in her left The letter

She did not seem as dead

But fast asleep, and lay as tho' she smiled."

TENNYSON'S "ELAINE.

Sir Thomas Malory says nothing of the meeting of Lancelot and Guinevere and the flinging of the diamonds into the Thames by the jealous Queen; but tells us that "by fortune King Arthur and Queen Guinevere were speaking together at a window; and so as they looked into the Thamse they espied the black barge, and had mervaile what it might meane." Tennyson describes the barge passing slowly to the doorway of the palace; the wonder of the armed sentinels at its appearance, the curious crowd that hastily assembled at the steps; the eager but fruitless questions asked, and the dumb oarsman's haggard face. It was thought he was enchanted, and that the beautiful lady so richly clad was a Fairy Queen, come, perhaps, to summon King Arthur; for, it was whispered, "Some say the King will not die, but will pass away into Fairy Land."

The news of the strange arrival reached the King, who accompanied by many of his knights went through the crowd to the river side. The Queen, too, having calmed her stormy heart by passionate tears, came too. The description by the old writer of what followed is so exquisite, that the modern poet has almost transcribed it:

"That faire corps well I see,' said King Arthur. And then the King took the Queene by the hand and went thither. Then the King made the barge to be holden fast; and then the King and Queene went in, with certain knights with them, and they saw a certain gentlewoman lying on a rich bed, covered unto her middell with many rich clothes, and all was of cloth of gold; and she lay as though she had smiled."

The dumb man rose and pointed to Elaine, and then to the door of the palace. Arthur understood the gesture, and bade the gentlest and the purest of his knights, Percivale and Galahad, to carry the beautiful corpse reverently into the hall. There they placed it, and the knights with silent footsteps gathered round to gaze on it. The light heart of Gawaine, who remembered how lovely she was in life, and with what a graceful modesty she had discouraged his courtly gallantries, was subdued to tenderness in the presence of the dead; and there was sorrow on the faces of all the knights and ladies who pressed forward curiously, but reverently, to see the fair corpse of the Lily Maid of Astolat, of whom they had so lately thought and spoken so much.

King Arthur reading the letter of Elaine

"Thus he read

And ever in the reading, lords and dames

Wept, looking often from his face who read

To hers which lay so silent."

TENNYSON'S "ELAINE."

And then came Lancelot, love for whom had been her death. Lancelot, whose presence had made the old hall at Astolat resplendent, whose voice, as he spoke of noble deeds and desperate adventures, had woke among the responding chords of her young heart the new melody of love; Lancelot, whose shield had been near her when she slept so innocently and sweetly in her tower chamber; who had worn on his helm her sleeve embroidered with the little pearls; Lancelot, for whom she had lived a short life of love it seemed the whole of life to her; for whose love she had pined and died, and to whom her cold body, with a smile as of loving lire on the face, had floated down the broad river.