|

|

The Lost Land Of King Arthur By J. Cuming Walters

CHAPTER VIII

OF ST. KNIGHTON'S KIEVE AND THE HOLY GRAIL

"The war-worn champion quits the world to hide

His thin autumnal locks where monks abide

In cloistered privacy." Wordsworth.

" Hither came Joseph of Arimathy,

Who brought with him the Holy Grayle (they say),

And preacht the truth: but since it greatly did decay."

Spenser.

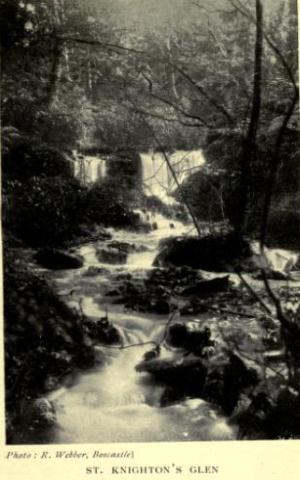

ABOUT a mile from Tintagel, along the hilly road leading to Boscastle, and passing the wonderful little Bossiney cove with its elephant-shaped rock, there is a small rapid stream which winds through the Rocky Valley and falls like a torrent at low tide into the sea. The Rocky Valley, with its three huge boulders, its narrow walk now leading to the side of the stream and now mounting far above it, and ending only where the iron cliffs beetle above the roughest of bays, is one of the most sublime spectacles that Nature has to display in that enchanted region. The scenery is a mixture of dark and frowning heights standing out with precipitous sides, and of green and gentle undulations, amidst which sparkles ever and anon the tinkling sinuous brooklet. But it is not so much the valley, despite its manifold charms, as the little stream, which has a special interest for the pilgrim. By devious ways its course may be traced back through a rushy channel which lies deep and almost hidden between two sets of well-wooded hills until suddenly the traveller hears the sound of a sharp splashing from an unseen cataract.

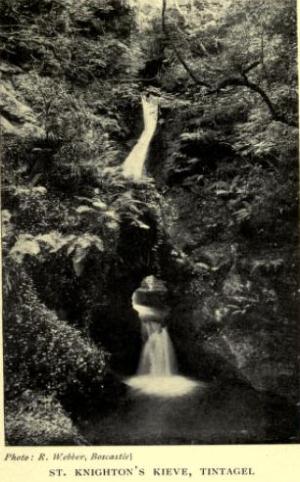

The walk now leads upward to a small gate; passing through the opening we descend once more a steep embankment and find ourselves at the water-edge. It is a haunted, sequestered spot, shut in by the hills, overcast by shadows, the one sound the sound of the leaping stream. This is St. Knighton's Kieve, once regarded with a species of holy awe in Cornwall and believed, like most natural wells or "basins," to be under the special protection and influence of a saint. The superstition is an old one, and slowly dying out, though the belief in holy wells, fairy wells, and wishing wells is one of the most pleasing and least harmful of all ancient fancies. Every spring was of yore regarded more or less as a miracle; every torrent had its tutelary genius.

The Kieve is a natural bowl into which the flashing cascade plunges from the rocks above. The water has worn its way through a narrow rocky crevice and drops through a natural bridge thickly overgrown with fern and moss. The dark Kieve receives the torrent, and the water spreads out again and dimples in the shallow bed, gliding smoothly and almost silently through the luxurious plantation. Now and then we catch its gleam among the lush foliage, and a mile or more beyond may be seen the deep blue of the sea into which it pours its tiny tribute. Below the edge of the Kieve is a flat slab, and the stream is broken as it shoots down; on one side is a bulging black rock which looks darker by contrast with the shining waters. The trees form a screen through which the light passes more dimly, and this secluded half-hidden spot is perceived to be a fitting scene for the stories it has inspired.

The Kieve as a place for complete retirement would, with many disadvantages, possess the one strong and desirable advantage of being difficult to discover without those written instructions as to the winding path which are now placed in the visitor's hands. For, lying a mile or more beyond the beaten track, it can be found only after a confusing journey through the thick brush and weeds of the valley, over rudely constructed bridges, up steep and slippery embankments, and finally through the doorway which is kept closed and locked against all comers save those who have begun the search from the right and legal road.

If we were to adhere strictly to Malory's narrative we should say that the quest for the Holy Grail began at Camelot. Local tradition, however, is privileged to depart from written records, and it happens that in this case the scene is transferred to this spot near King Arthur's birthplace. We are asked to believe that the knights, standing with bowed heads in the Kieve, undertook the search for the Holy Vessel of the Last Supper, brought by Joseph of Arimathaea to this land, the Cup that had been hidden and lost, and was destined to be discovered only by the pure and perfect knight. The king, standing on the bridge of rock above the torrent, watched his reverent followers in the stream below laving their brows in its waters, listening to the music of the fall, and, full of the inspiration of the scene, making their solemn vows, and with a firm desire after righteousness setting forth upon the quest. Lancelot and Bors, Perceval and Galahad, when in the wild woods far distant or among the ruined

Of St. Knighton's Kieve 187

chapelries, when tormented by doubts and wrestling with foes, might be expected to recall that cool and shady gathering-place, to see in a vision the flashing cascade, to dream of the crystalline brightness of the plunging water, and with renewed hope and courage to continue their hard task.

Some such sequestered place the poet of " Sir Galahad, a Christmas Mystery," may have had in mind when he pictured the lonely knight struck with awe by hearing a voice which said that the great Quest would be achieved by him alone

"Following

That hoiy Vision, Galahad, go on."

To this very spot, too, if legend be true, the knights who had failed returned.

The story of the Holy Grail is too profound and complex a study to be treated in these pages save in the most superficial and limited manner. Volumes have been and still can be devoted to the subject, and yet not exhaust all that is to be told of this world-legend with its infinite variations and its numberless phases and meanings. Like a river of many obscure sources, most of which are now partly known, thanks to the perseverance of the most devoted and painstaking of exploring scholars, it gathers in volume upon the way, and to trace it backward or onward involves an equally long and tortuous journey. The primary form of the legend, the actual beginning of the Grail romance cycle, remains a mystery and seemingly undiscoverable. The oldest poems on the subject, those of Christien de Troyes and Robert de Borron, were founded upon a model, or models, absolutely untraced. That it was a primitive Celtic tradition admits of no doubt, but when Walter Map incorporated the legend into the Arthurian story in the thirteenth century there 'were Latin, German, and French originals for him to work upon. In one chief version of the narrative Perceval is the supreme figure; in the other Galahad, Perceval, and Bors all achieve a measure of success, the first named being the absolute victor and the others being admitted to partial triumph. The Christian element in the cycle is distinct almost throughout, and the many versions have one point in common the sanctity of the Grail, its connection with the Saviour, or with John the Baptist, and its continued miraculous power proceeding from this connection. But the Celtic originals would be free from traces of Christian symbolism. In Malory we find the Holy Vessel in the possession of King Pelleas, nigh cousin to Joseph. When the king and Sir Lancelot went to take their repast a dove entered the window of the castle, and she bore in her bill a little censer of gold from which proceeded a savour as if all the spicery of the world had been there. The table was forthwith filled with good meats and drinks by means of the Grail, "the richest thing that any man hath living," as King Pelleas declared. Whether the Grail was a chalice which received the blood of the crucified Lord; whether, as others have affirmed, it was the dish on which the head of John the Baptist had lain; or whether it was a miraculous stone which fell from the crown of the revolting angels made for Lucifer, the belief in its reality in early times must have been sincere and ineradicable. It was said to have sustained Joseph during an imprisonment of forty-two years; the fisherman king, Pelleas, needed no food while it was in his keeping. This is set forth in Wolfram's "Parzival"

"Whate'er one's wishes did command,

That found he ready to his hand."

Wolfram von Eschenbach, to whom both Germans and English owe so much, found a collection of badly joined fables which he turned into an epic, making Parzival (Perceval) the hero and the Grail quest the central incident. Wolfram knew nothing of Joseph of Arimathaea; but Mr. Alfred Nutt has pointed out that the Joseph form of the Grail story and the Perceval form may really form one organic whole, or the one part may be an explanatory after-thought. Whether the Christian element was influenced by Celtic tradition, or whether the Christian legend was superimposed upon the Celtic basis, is the subtle point which few care to say is decided. The suggestion has been thrown out that the Grail legend may even be of Jewish origin, and that in singing of their Holy City whose walls should be called "salvation," whose gates "praise," and whose "stones should be laid in fair colours," they supplied the germ from which in mediaeval ages the Grail-myth sprang. The Grail was an article of strong belief with the Templars who worshipped the head of John the Baptist, which v/as reported to have been found in the fourth century, to have kept an Emperor from dying at Constantinople, and to have provided nourishment for all who were engaged upon religious crusades. The idea of the Holy City seems again to recall the aspiration of the Templars, and the Sarras of romance may have been none other than Jerusalem. Mr. Nutt has been able to adduce Celtic parallels for all the leading incidents in the romance of the Grail, while the many inconsistencies in the versions are explained by the fusion of two originally distinct groups of.stories. It is, as Mr. Nutt aptly says, the Christian transformation of the old Celtic myths and folk-tales which "gave them their wide vogue in the Middle Ages, which endowed the theme with such fascination for the preachers and philosophers who use it as a vehicle for their teaching, and which has endeared it to all lovers of mystic symbolism."

Four of Malory's "Books" treat of the quest of the Holy Grail and of the adventures of the knights who undertook it. These "Books" supply the spiritual and religious leaven of the romance. Only by stainless and honourable lives, not by prowess and courage, so the knights were taught, could the final goal be reached. Success in the tournament and in war was achieved by inferior means. Hardihood and skill were of no avail where the Grail was the prize. " I let you to wit," said King Pelleas, "here shall no knight win worship but if he be of worship himself and good living, and that loveth God; and else he getteth no worship here, be he ever so hardy." Sinful Lancelot was fated to test this truth. Struggle manfully as he would, victory was not for him, though, as the old hermit told Sir Bors, "had not his sin been, he had passed all the knights that ever were in his days"; but "sin is so foul in him that he may not achieve such holy deeds." The devoted knights might speak of Lancelot's nobleness and courtesy, his beauty and gentleness, but the quest was not for him. His expiation was severe. Of the hundred and fifty knights "the fairest fellowship and the truest of knighthood that ever were seen together in any realm of the world whom King Arthur reluctantly allowed to seek for the Grail, only one, the virgin Galahad, could enter the Castle of Maidens and deliver the prisoners, could hear the voices of angels foretelling his triumph, could find the Grail, and could be crowned in the holy city of Sarras, the 'spiritual place.' 'It was in this city that Joseph had been succoured; it was here that Perceval's sister was entombed; it was here by general assent that the pure Galahad was proda med king; and it was here that the Grail remained. " And when he was come for to behold the land, he let make about the table of silver a chest of gold and of precious stones, that covered the holy vessel; and every day in the morning the three fellows (Perceval and Bors with Galahad) would come before it, and say their devotions."

At the year's end Galahad saw a man kneeling before the Grail; he was in the likeness of the bishop: it was Joseph. The saint told the virgin knight that his victory had been complete and his life perfect. "And therewith," runs the beautiful chronicle, "he kneeled down before the table and made his prayers; and then suddenly his soul departed unto Jesus Christ, and a great multitude of angels bare his soul up to heaven that his two fellows might behold it; also, his two fellows saw come from heaven a hand, but they saw not. the body, and then it came right to the vessel and took it, and the spear, and so bare it up to heaven. Since then was there never a man so hardy for to say that he had seen the Sancgreal."

We turn instinctively to Tennyson for the poetisation of this incident. No one has worked on the legends so wondrously as he, no one has added more to their moral significance or to their mysticism. His paraphrase of the prose of Malory, his additions to the details, and his glorification of the vision, rank among the greatest triumphs of his peculiar art.

With what feelings is one likely to read his Holy Grail, and, standing near the broken and gleaming torrent of St. Knighton's Kieve, try to imagine that the marvellous quest which ended in Sarras began at this spot?