|

|

The Lost Land Of King Arthur By J. Cuming Walters

CHAPTER X

OF GLASTONBURY AND THE PASSING OF ARTHUR

" And so they rowed from the land; and Sir Bedivere beheld all the ladies go with him. Then Sir Bedivere cried, Ah my Lord Arthur, what shall become of me now ye go from me, and leave me here alone among mine enemies? Comfort thyself, said the King. For I will go into the vale of Avilon, to heal me of my grievous wound. And if thou never more hear of me, pray for my soul." Malory.

" Whether the Kinge were there or not,

Hee never knewe, nor ever colde,

For from that sad and direful daye

Hee never more was scene on molde." Percy Reliques.

" O, three times favoured isle, where's the place

that might

Be with thyself compared for glory or delight

Whilst Glastonbury stood? . . .

Not great Arthur's tomb, nor holy Joseph's grave,

From sacrilege had power their sacred bones to save,

He, who that God in man to his sepulchre brought,

Or he, which for the faith twelve famous battles fought."

Drayton.

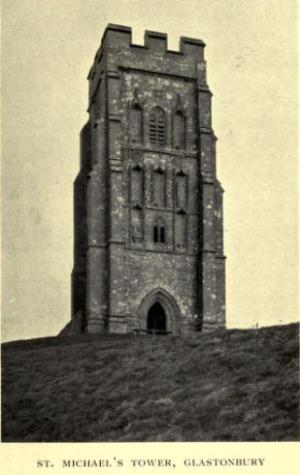

A QUAINT old-world look is upon the face of the city of many legends, King Arthur's "isle of rest." It lies deep in a green well-watered valley, and its steep sudden hill, the Tor, rising abruptly to a height of over five hundred feet and crowned with a lonely square tower, seems to shelter and keep watch upon the traditional apple-island. The orchard lawns are seen everywhere with their deep-green carpet and the crooked branches of innumerable fruit-laden trees casting grotesque shadows upon it. The whole year round the western airs are balmy, though in spite of hoary legend and poetic eulogy Glastonbury has felt the effects of terrific storms, whirlwinds, and earthquakes. Its history a history of marvel and wonder, inextricably mingled for many centuries with superstition takes us far back into the misty past when the ancient Britons named the marshland, often flooded by the water of the Bristol Channel, Ynyswytryn, or Inis vitrea, the Glassy Island; either, it has been surmised, on account of the "glasten " or blue-green colour of its surface, or from the abundance of "glass" (or woad) to be found in the vicinity.*

* Glastonbury occupies a former site of Druidical worship, and Professor Rhys believes the name to be a corruption of the British word glasten, an oak, the Druids cultivating both the oak and the apple as foster parents of their sacred mistletoe. Glestenaburh, says Canon Taylor, was assimilated by the Saxons to their gentile form Glestinga-burh or Glagsting-burh, which being supposed by a false etymology to mean the " shining " or " glassy " town was mistranslated by the Welsh as Ynys-Widrin, the Island of Glass.

On the other hand Professor Freeman believed that Glastonbury was the abode and perhaps the possession of one Glaesting, who, on discovering that his cattle strayed to the rich pastures, settled in that part, which in the natural order of things became Glsestingaburgh. That it was veritably an island admits of no doubt; the circuit of the water can still be traced; and when the Romans in turn made discovery of the fruitfulness of the region enclosed by the waters of the western sea, they denominated it Insula Avalonia, or Isle of Apples. This was the " fortunate isle," celebrated in the ancient ode of which Camden has given us a version, "where unforced fruits and willing comforts meet," where the fields require "no rustic hand " but only Nature's cultivation, where

" The fertile plains with corn and herds are

proud,

And golden apples shine in every wood."

The inflowing of the sea made islands not only of Glastonbury, but of Athelney, Beckery, and Meare; and not many centuries ago, when a tempest raged, the sea-wall was broken down and the Channel waters swept up the low-lying land almost as far as Glastonbury Church. The simple record of this event reads: " The breach of the sea-flood was January 2oth, 1606." Again in 1703 was Glastonbury threatened with a deluge, and the water was five feet deep in its streets; but as geologists are able to affirm that the sea is receding from the western coast it is unlikely that such catastrophes will recur. A little lazy stream, the Brue, almost engirdles the city, and thus permits the inhabitants with seeming reasonableness to retain for Glastonbury the name loved best the Isle of Avalon. That Roman name has been full of dreamy suggestiveness to the poet's mind; and though the poet's Avalon may often have been an enchanted city, the "baseless fabric of a vision," the Avalon of Somerset, with its two streets forming a perfect cross, its Abbey ruins, its antiquities, and its slumbrous aspect, is assuredly not unworthy of the legends clustering about it.

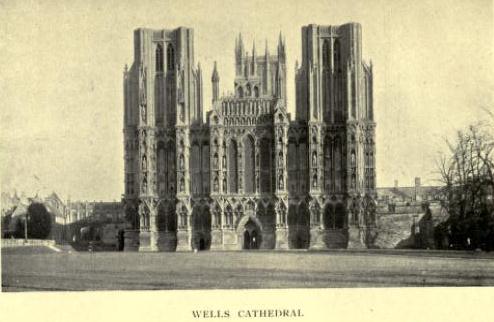

Only by devious paths can Glastonbury, once the remote shrine for devout pilgrims from all parts of the land, be reached, for it is still somewhat out of the common track. But to wander awhile in the apple-country is delightful alike to the mind and the physical sense to drink in its associations, to inhale its warm, sweet air, to see the gleam of white blossoms and the crimson softening upon the round ripened cheeks of the pendent fruit, these are the sources of enjoyment and the elements of the charm. Countless gardens send forth a rare perfume, and the quiet of the whole city in the midst of orchards and streams and showing the relics of by-gone splendour has a lulling effect upon the traveller who comes from the roaring town and the busy mart. When the twin dark towers of Wells Cathedral are fading shadow-like in the distance the new strange picture of the island-valley is revealed. There stretch the long level meadows of deep emerald, there glooms a forest of trees whose twisted branches are bright with apple-blossoms. The high Tor hill looks stern and bare, but cosy and inviting is the town below with its rows of irregular houses, many of which date back to long past days, while others, constituted of stone with which the architects of Dunstan's and of Becket's time wrought, seem to bear mute tribute to the famous era when the Abbey was in its glory and reverend pilgrims from afar came to bring oblations to that hallowed shrine. To-day the visitor finds a welcome at the "Inne" built in 1475 for the devout travellers whom the Abbot could not accommodate within the walls of the Abbey; and so few are the changes of time that the lofty facade, the parapet and turrets, the wide archway, the ecclesiastical windows, and the long corridors, remain almost as they were first designed and made. Side by side stand "Ye Olde Pilgrim's Inne " and the Tribunal, or Court House, built by Abbot Beere, for the trial of petty offenders against the law. Unexplored dungeons are reported to exist underground, together with subterranean passages' communicating with the Abbey from the "Inne" and the Tribunal.

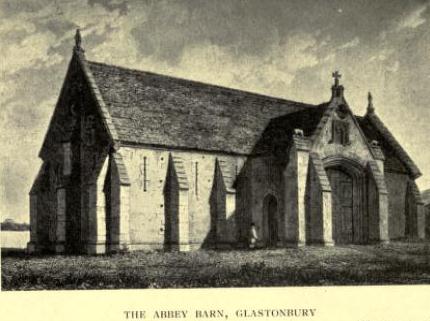

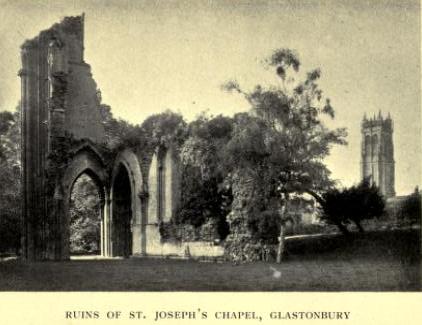

In the neighbourhood is a conspicuous building once used for collecting the tithes, called the Abbey Barn, dating from 1420, in some respects the best preserved of all the ancient memorials. But the pride and glory of Glastonbury centre in the wondrously beautiful remains of the oldest, richest, and stateliest of English Abbeys an Abbey whose reputed founder was Joseph of Arimathaea, that Joseph who had seen the face and heard the voice of the Saviour of mankind. It was the only church of first rank in England standing as a monument of British days which escaped the scath and wreck which followed the storm of Norman conquest.

To what dim epoch the earliest history of Glastonbury belongs is more or less conjectural, though the discovery of some sixty low mounds by archaeologists led to the discovery that a prehistoric lake-village in remote times occupied the site. Excavations revealed the remains of human habitations and of successive occupation by the same race a race which hunted the boar, the roebuck, and the deer, and whose sole accomplishment was the making of coarse, rude pot tery. But this people has passed away and not even a tradition of its existence is extant. It was at a much later period, though, looking backward, the time seems far distant, that the first legend of Glastonbury took root and flowered. So pure, fragrant, and beautiful is that treasured blossom that it would seem ruthless to attempt to pluck it by the roots from the ground, and to cast it aside as a worthless weed of ignorance and superstition. It brings to us the memory of that time when the Son of Man was on earth; it is a seed blown from that land which His presence sanctified. Nearly two thousand years ago the crucified Nazarene was watched by agonised crowds upon Calvary. Joseph of Arimathaea, "a good man and a just," begged the dead body from Pilate and buried it in his own garden, thereby incurring the fierce resentment of the Jews. He fled from Palestine, fearing for his life, and so enraged were his enemies at his escape that they expelled his friends also Lazarus, Mary Magdalene, and Philip among others putting them out to sea without oars or sail. "After tossing about many days," says one writer, "they were driven in God's providence to Marseilles, and from Marseilles St. Joseph came to Britain, where he died at a good old age, after having preached the Gospel of Christ with power and earnestness for many years." This was about A.D. 63. "The happy news of the Saviour's resurrection, and the offer of the only assured means of salvation to all who would embrace it" were welcomed by King Arviragus, who assigned to St. Joseph the Isle of Avalon as a retreat.

When Joseph and his little Christian band, passing over Stone Down where stand the two notable Avalon Oaks, came to the place, weary with long travelling, they rested on the ridge of a hill, which in its name of Weary-all Hill (really Worall) is supposed to commemorate this incident; and where the saint's staff touched the sod, a thorn tree miraculously sprang up, and every Christmas Day it buds and blossoms as a memorial of our Lord, and of the first Christian festival.*

* William Morris slightly varied the story in his

King Arthur's Tomb, when he represents Lancelot journeying to

"where the Glastonbury glided towers shine " and relates that

"Presently

He rode on giddy still, until he reach'd

A place of apple-trees, by the Thorn-Tree

Wherefrom St. Joseph in the past days preach'd."

Another story says that the saint

was met by a boisterous mob of the heathen, and that, planting

his pilgrim's staff in the earth, he knelt down to pray; and as

he prayed, the hard, dry staff began to bud and give forth

fragrance, and became a living tree. Then said Joseph, "Our God

is with us," and the heathen, transfixed by the miracle, were

convinced and pacified. So runs the earliest Christian legend in

England, and as a fitting sequel we learn that not long after

Joseph's mission had begun the first Christian chapel was built,

and occupied part of the site on which the most beautiful of holy

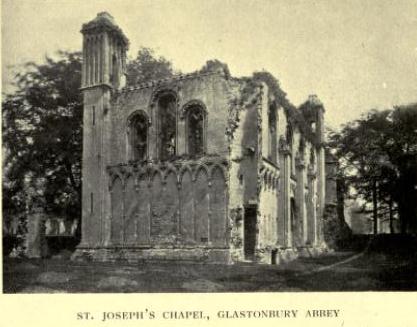

houses was afterwards reared Glastonbury Abbey. St. Joseph's

Chapel, magnificent in ruin, is one of those hallowed places in

which one might spend hours in silent contemplation. Through many

centuries the legend of the Holy Thorn has been preserved, and

Glastonbury has remained distinguished by the fact that there the

" winter thorn " has blossomed every Christmas "mindful of our

Lord," or, as a pupil of Caxton's wrote in 1520

Another story says that the saint

was met by a boisterous mob of the heathen, and that, planting

his pilgrim's staff in the earth, he knelt down to pray; and as

he prayed, the hard, dry staff began to bud and give forth

fragrance, and became a living tree. Then said Joseph, "Our God

is with us," and the heathen, transfixed by the miracle, were

convinced and pacified. So runs the earliest Christian legend in

England, and as a fitting sequel we learn that not long after

Joseph's mission had begun the first Christian chapel was built,

and occupied part of the site on which the most beautiful of holy

houses was afterwards reared Glastonbury Abbey. St. Joseph's

Chapel, magnificent in ruin, is one of those hallowed places in

which one might spend hours in silent contemplation. Through many

centuries the legend of the Holy Thorn has been preserved, and

Glastonbury has remained distinguished by the fact that there the

" winter thorn " has blossomed every Christmas "mindful of our

Lord," or, as a pupil of Caxton's wrote in 1520

" The hawthornes also that groweth in Werall

Do burge and here green leaves at Christmas

As fresh as other in May."

The tree was regarded with great awe and superstition by the inhabitants, and when the change in the calendar was made they looked to the "sacra spina" for confirmation of the righteousness of what had been done. Many people refused to celebrate the new-style Christmas Day because the Thorn showed no blossoms, and when the white flowers appeared on January 5th, the old-style Christmas was held to have been divinely sanctioned. A trunk of the tree was cut down by a Puritan soldier, though his sacrilege caused him to be severely wounded by a piece of the dismembered tree striking him; but when the Thorn was cast into the river as dead and worthless it miraculously took root again. The spot where it grew is marked by a monumental stone bearing the inscription: I. A. A.D. XXXI.

A Somerset historian likewise records that in addition to the Holy Thorn there grew in the Abbey churchyard a miraculous walnut tree, which never budded forth before the feast of St. Barnabas, namely, the nth of June, and "on that day shot forth leaves and flourished like its usual species." This tree is, gone, but another "of the commonplace sort" stands in its place. " It is strange," we read, "to say how much this tree was sought after by the credulous; and though not an uncommon walnut, Queen Anne, King James, and many of the nobility of the realm, even when the times of monkish superstition had ceased, gave large sums of money for small cuttings from the original." The walnut tree, however, never vied with the Holy Thorn in popularity. The "Athenian Oracle" (1690) wriggled out of the difficulties attending a belief in the budding of the hawthorn tree with characteristic ingenuity, and supplied an example that most of us would gladly imitate. To an inquirer who asked for information and an opinion, the "Oracle" replied (none too grammatically), "All that Mr. Camden says of it is, that if any one may be believed in matters of this nature, this has been affirmed to him to be true by several credible persons; it was not in Glastonbury itself, but in Wirral Park, hard by it; however, this superstitious tree, true or false, was cut down in the last reforming age, though it seems they did not make such root and branch work with it but that some stumps remained, at least some branches or grafts out of it were saved, and Still growing in the same country; though whether they have the same virtue with the former, or that had any more than any other hawthorn, we don't pretend to -determine any more than the fore-mentioned historian." The belief in the tree and the knowledge of its peculiar properties were so wide-spread that Sedley's verse on Cornelia, who "bloomed in the winter of her days like Glastonbury Thorn " was easily understood. Bishop Goodman, writing to the Lord General Oliver Cromwell in 1652, said he could "find no naturall cause" either in the soil or other circumstances for the extraordinary character of the tree. "This I know," said the prelate, "that God first appeared to Moses in a bramble bush; and that Aaron's rod, being dried and withered, did budde; and these were God's actions, and His first actions; and, truly, Glastonbury was a place noted for holiness, and the first religious foundation in England, and, in effect, was the first dissolved; and therein, was such a barbarous inhumanity as Egypt never heard the like. It may well be that this White Thorne did then spring up, and began to blossome on Christmas day, to give a testimony to religion, and that it doth flourish in persecution," and so forth. Infinite meanings and significances could be extracted from the legend, that fantastic casket of man's art and devising which is made to enshrine the small pure pearl of truth. If this were the place for sermons it might be pointed out that the vitality of the Thorn is an emblem of the vitality of the religion it commemorates; but our duty is to trace its connection with history. The legend has been somewhat altered in form in order to bring it into direct association with the building of the Abbey. This new version of the miracle is that Joseph of Arimathaea was commanded to build a church in honour of the Virgin Mary, but finding that the natives were distrustful of him and his mission he prayed, like Gideon, for a miracle. Forthwith his staff began to shoot forth leaves and blossoms, and the unwithered Thorn took root. Be that as it may, the first Christians built a chapel of twisted alder, in the form of a parallelogram, 60 feet long and 26 feet broad (to come to details), and having "a window at the west end and one at the east; on each side were three windows, and near the western angle was a door each side." A representation of the first building for Christian worship erected in this country is found on an old document now in the British Museum, and it is said to have been copied from a plate of brass which had been affixed to an adjoining pillar. The chapel is variously referred to in ancient records as "Lignea Basilica," "Vetusta Ecclesia," and the "Ealdechirche," and with its walls of wattles and its roof of rushes it must long have been an object of revered contemplation. Joseph built and preached in "the little lonely church," "built with wattles from the marsh," journeying from thence across the plain to the Mendips, where he found other half barbarous Britons to listen to the story of the Redemption. He laid the foundations of a bishopric at Wells, which was afterwards to be the rival of Glastonbury Abbey itself, and to the end of a long and fruitful life continued his ministry to the people.

Chalice Hill revives by its name and associations another reminiscence of our Lord even more amazing. St. Joseph was the bringer to this country of two precious relics one

"The Cup itself from which our Lord

Drank at the last sad supper with His own,"

the other, some of the blood which oozed from the crucified Saviour's body. The chalice, or sacred cup, was buried by Joseph at the spot where a perpetual spring of water bubbles the "Blood Spring," which supplies the Holy Well, scene of many miraculous cures in times past. That the waters are medicinal admits of no doubt; that it issues from the Cup is a matter of faith, especially as the Holy Grail is claimed to be now in safe keeping by more than one far-distant Abbey.*

* The Holy Grail is pointed out in particular at Genoa Cathedral. "It was brought from Caesarea in 1101, is a hexagonal dish of two palms' width, and was long supposed to be of real emerald, which it resembles in colour and brilliancy."

As for the second relic, it is said that St. Joseph confided the memorial to his nephew Isaac, who sealed up the blood in two vials and secreted them from the invading Roman pagans. When danger menaced him, he hid the phials in an ancient fig-tree, which he then cast into the sea. Carried by the waves to Gaul, the fig-tree was cast up at the spot which now forms Fecamp harbour; and there a few centuries later it was found with the two phials secure. Fearless Duke Richard of Normandy was so impressed by the discovery that he built an Abbey in which fitly to enshrine the Precious Blood, and Fecamp Abbey bears witness alike to his faith and his devotion. It was upon the story of the Grail that chroniclers seized with avidity after Borron had once shown its capabilities a story now believed by many to be almost wholly of Celtic origin, the Sancgreal being none other than Fionn's healing cup. Mr. Nutt, to whose exhaustive work on the subject reference has previously been made, has told us of every form, rudimentary and developed, in which the Grail legend has appeared, and of every explanation advanced as to its meaning.

Whether the legend is based upon Christian canonical or uncanonical writings, or whether it is an ancient saga into which a Christian element was imported, whether it was extant in any definite form before the time of Robert de Borron, or whether it was a fabrication of the era to which many monkish fables have been traced, are points which to discuss in detail would require, and have had, volumes devoted to them. Within fifty years (1180-1225) there were eight versions of the story in which the idea of the Grail was elaborated, and we know how the idea has been developed and enriched and idealised until our own time. "The vanished Vase of Heaven that held like Christ's own Heart an Hin of Blood," has been a marvellously fecund seed of inspiration to romancist and poet. Percival and Galahad are the highest human conceptions of purity, and their quest is the most exalting and ennobling upon which heroes can set forth.

Yet, as we have already seen, the conclusion cannot be resisted that the story had its root in paganism, and that the history of the Grail is nothing but the history of the gradual transformation of old Celtic folk-tales into a poem charged with Christian symbolism and mysticism. "This transformation, at first the inevitable outcome of its pre-Christian development, was hastened later by the perception that it was a fitting vehicle for certain moral and spiritual ideas." Avalon, lying not far from the western sea beyond which tradition said were the happy isles of the blessed dead, was the Cymric equivalent for the Celtic paradise, and thus did Glastonbury become associated with the glorious legends which have made it in the eyes of the romancists the most sacred and wondrous city of earth. So may Glastonbury truly be said to gather round it " all the noblest memories alike of the older and the newer dwellers in the land." Nor is it surprising that in a place of so much reputation modern marvels should be reported to occur or wonderful discoveries be made. An elixir was found in the ruins of the Abbey in 1586, one grain of which, being dropped upon an ounce and a quarter of mercury, was found to transmute the mercury into an ounce of pure gold. Another grain of it, dropped upon a piece of metal cut out of a warming-pan, turned the metal into silver, and this with the warming-pan was sent to Queen Elizabeth that she might "fit the piece with the place where it was cut out."

Such facts are worthy of being related at some length not only on account of any curious interest they possess in themselves, but because they enable us to understand a number of allusions in the Arthurian story, and help to account for the selection of Glastonbury as the scene of the most solemn episodes in the career of the British king and his knights. The poet Spenser, in recording that Sir Lucius was the first to receive "the sacred pledge of Christ's evangely," hastens to recall the Glastonbury legend, and to explain that

"Long before that day

Hither came Joseph of Arithmathy,

Who brought with him the Holy Grayle, they say,

And preacht the truth."

All the chief points in the old beliefs and the myths and traditions are caught up in Malory's history. The account of Joseph and his coming to England may be read in the Book of Sir Galahad, for the story was told by the stainless knight who bore the marvellous shield-

" Sir," said Sir Galahad, " by this shield beene full many mervailes." " Sir," said the knight, " it befell after the passion of our Lord Jesu Christ thirtie yeare, that Joseph of Aramathy, the gentle knight, that tooke downe our Lord from the crosse, and at that time hee departed from Jerusalem with a great part of the kindred with him, and so they laboured till they came to a citie that hight Sarras. And at that same houre that Joseph came unto Sarras there was a king that hight Evelake, that had great warre against the Sarasins, and in especial against one Sarasin, the which was King Evelake's cosin, a rich king and a mighty, the which marched nigh this land, and his name was called Tollome le Feintes. So, upon a day these two met to doe battaile. Then Joseph, the son of Joseph of Aramathy, went unto King Evelake, and told him that he would be discomfited and slaine but if he left his beleeve of the ould law and beleeve upon the new law. And then he shewed him the right beleeve of the Holy Trinity, the which he agreed with al his hart, and ther this shield was made for King Evelake, in the name of him that died upon the crosse; and then through his good beleeve hee had the better of King Tollome. For when King Evelake was in the battaile, there was a cloath set afore the shield, and when hee was in the greatest perill hee let put away the cloath, and then anon his enemies saw a figure of a man upon the crosse, where through they were discomforted. And so it befell that a man of King Evelake's had his hand smitten off, and beare his hand in his other hand, and Joseph called that man unto him, and bad him goe with good devotion and touch the crosse; and as soon as that man had touched the crosse with his hand, it was as whole as ever it was before. Then soone after there fell a great mervaile, that the crosse of the shield at one time vanished away that no man wist where it became. And there was King Evelake baptised, and for the most part all the people of that cittie. So soone after Joseph would depart, and King Evelake would go with him whether he would go or not; and so by fortune they came into this land, which at that time was called Great Brittaine, and there they found a great felon panim that put Joseph in prison. And so by fortune tidings came unto a worthy man that hight Mondrames, and hee assembled all his people, for the great renown that he had hard of Joseph; and so he came into the land of Great Brittaine, and disherited the felon panim and consumed him, and therewith delivered Joseph out of prison. And after that, all the people were turned to the Christian faith."

According to Malory it was "Not long after that," that Joseph was "laid in his death bed," his last act being to make "a crosse of his owne blood " upon the shield before giving it to King Evelake. " Now may yee see a remembrance that I love you," he said, "for yee shall never see this shield but that yee shall thinke on mee, and it shall be alwayes as fresh as it is now. And never shall no man beare this shielde about his necke but hee shall repent it, unto the time that Sir Galahad the good knight beare it." It is the general opinion that Joseph of Arimathaea was buried in the ground surrounding the church of his foundation, for a burial ground to contain a thousand graves had been prepared in his time. William of Malmesbury wrote that there were preserved in that consecrated place "the remains of many saints, nor is there any space in the building that is free of their ashes. So much so that the stone pavement, and indeed the sides of the altar itself, above and below, is crammed with the multitude of the relics. Rightly, therefore, it is called the heavenly sanctuary on earth, of so large a number of saints it is the repository." There is no clear record of who immediately succeeded Joseph, but his ministry was carried on by St. Patrick, who was a native of Glastonbury,* by St. David, by Gildas, and by Dunstan. It was St. Patrick who, returning from his labours in Ireland in 461, found that the church built with wattles from the marsh was in a state of decay, and erected a substantial edifice on Tor Hill, dedicated to St. Mary and St. Michael. He was Glastonbury's first abbot, though this fact is traditionary rather than historical, and his grave was near the altar of the original church. An oratory had previously existed on the site, having been founded a century after Joseph's arrival by two saints, Phaganus and Duruvianus. The Abbey itself now began to take definite shape, the eyes of all Christians being drawn to Glastonbury by reason of its sacred record. In the sixth century, in King Arthur's time, it was approaching its fulness of power and nearing that zenith of fame and splendour which did not decline for nearly a thousand years.

* Some historians, perhaps with better reason, declare that he was born in 405 at Kilpatrick, Dumbarton, a little town at the junction of the Levin and Clyde. He is variously reported to have died in 493 and 507, some placing his age at 88, and others at 120.

According to Professor Freeman, Glastonbury became, in the year 60 1, the great sanctuary of the British in the place of Ambresbury, which had but lately fallen. How it grew, how it was ruled by great leaders in the church, how it became the largest, the most beautiful, the most wealthy of all abbeys, how its fall was compassed, and how the last of its abbots, an aged man, was dragged to the hill-top and hanged, are historic facts which belong to a date far later than that with which we are concerned. We cannot even dwell upon St. Patrick's sojourn at Glastonbury, or upon Dunstan's retirement to its cloisters in order to devote himself to study and music. Here it was that he wrestled with the Evil One in person while labouring at his forge; here it was that heavenly visions were vouchsafed to him; here it was that he began his work of reformation in the Church and made the Abbey the centre of religious influence in the kingdom. After the lapse of centuries we gaze only upon the ruins of the fabric, and from them learn how majestic the temple in its prime must have been, comprehending a little of the truth half revealed and half concealed in the silent stoned places with their shattered walls, their crumbling archways, their unroofed chambers, their windows darkened with trailing weeds, and their floors overgrown with lank grasses and moss.

King Arthur's connection with Glastonbury cannot be deemed wholly mythical, though the mysteriously beautiful narrative which tells of his last days in Avalon seems too poetical for reality. There are, however, other links, not so generally recognised, connecting him with this consecrated place. Glastonbury was not only his "isle of rest;" nor was the Abbey known only to him as a shrine. He claimed, or it was claimed for him, that he was descended on his mother's side from Joseph of Arimathaea, the genealogy being thus given: " Helianis, the nephew of Joseph, begat Joshua; Joshua begat Aminadab; Aminadab begat Castellos; Castellos begat Mavael; Mavael begat Lambord, who begat Igerna of whom Uther Pendragon begat the famous and noble Arthur." Glastonbury, in addition to its celebrity as a Christian sanctuary, would therefore have a claim upon King Arthur's attention for the sake of his venerated ancestor, though there seems little reason to doubt that in his day it was the cynosure of the eyes of all who claimed to be within the religious fold. Lady Charlotte Guest, in one of the valuable notes to her translation of the Mabinogion, calls attention to a record of William of Malmesbury, which proves how much Glastonbury was in King Arthur's mind on all occasions.

"It is written in the Acts of the illustrious King Arthur," we read, "that at a certain festival of the Nativity, at Caerleon, that monarch having conferred military distinction upon a valiant youth of the name of Ider, the son of King Nuth, in order to prove him, conducted him to the hill of Brentenol, for the purpose of fighting three most atrocious giants. And Ider, going before the rest of the company, attacked the giants valorously, and slew them. And when Arthur came up he found him apparently dead, having fainted with the immense toil he had undergone, whereupon he reproached himself with having been the cause of his death, through his tardiness in coming to his aid; and arriving at Glastonbury, he appointed there four-and-twenty monks to say mass for his soul, and endowed them most amply with lands, and with gold and silver, chalices, and other ecclesiastical ornaments." From this we might well infer that King Arthur was in the habit of paying periodical visits to the island-valley. "The great Lady Lyle of Avelyon," girt with a sword which only Balin could draw from its scabbard, with results afterwards disastrous to himself, is a link in the associations of Arthur and his court with the island-valley.

His war with King Melvas, of Somersetshire (strongly reminiscent of the last war with Mordred, as related by Malory), reads like veritable history. While engaged in subduing the savage hordes in Wales and Cornwall, and in beating back the advancing Saxons, he found that the " Rex Rebellus " Melvas had stolen away his wife Guinevere, and carried her to Ynyswytryn. King Arthur gathered a large force, and set out with his knights to take summary vengeance on the ravisher, whom he forthwith besieged. A wellknown antiquary has found reason to believe that Arthur's force was "a numberless multitude;" but at all events there is little doubt that Melvas, who was only an "underlord," would have been heavily defeated had a battle ensued. But conflict was avoided by the intervention of Gildas, the Abbot, who commanded Melvas to restore Guinevere to her rightful lord, and then succeeded in reconciling the two foes. They both ended by swearing friendship and fidelity to the Abbot, and the facts go far to show the potentiality of that dignitary at this period. Thus, by establishing King Arthur's connection with Glastonbury, we increase the likelihood of his choosing the holy place at Avalon for his last restingplace. He knew the shrine well and had visited the fruitful, balmy island-valley in which his ancestor's name was deeply revered; and when his time drew nigh he could think of no sweeter, better spot in which to seek for peace. "Comfort thy selfe," said the king to weeping Sir Bedivere after the last battle, "and do as well as thou maiest, for in mee is no trust for to trust in; for I wil into the vale of Avilion for to heale me of my grievous wound; and if thou never heere more of me, pray for my soule." And with the three mourning queens he passed from the bloody field of Camlan up the waters of the Bristol Channel to the isle

"Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly."

"King Arthur, being wounded in battle, was brought to Glastonbury to be healed of his wounds by the healing waters of that place," an old record runs. But his wound was too grievous; and though Merlin prophesied that he "cannot die," the current tradition is that when he reached the sacred isle he "came unto his end." In the time of the first Plantagenet, when the fame of King Arthur was revived, search was made at Glastonbury for the bones of the great British chief. Henry II. was then on his way to Ireland, and Henry of Bloys, then Abbot of Glastonbury, undertook the task, fully intending, no doubt, that it should be successful. Between two pillars at a depth of nine feet a stone was found with a leaden cross inscribed on its under side in Latin, "Here lies buried the renowned King Arthur, in the isle of Avalon"; and seven feet lower down his body was found in an oaken coffin.

The historian Selden gives us an instructive report of how King" Henry was induced to set about the strange enterprise of discovering the remains of King Arthur. He tells us that the king in his expedition towards Ireland was "entertained by the way in Wales with bardish songs, wherein he heard it affirmed that in Glastonbury (made almost an isle by the river's embracements) Arthur was buried betwixt two pillars. He therefore gave commandment to Henri of Blois, then Abbot, to make search for the corps, which was found in a wooden coffin (Girald saith oaken, Leland thinks alder), some sixteen foot deep; but after they had digged nine foot they found a stone on whose lower side was fixt a leaden cross (crosses fixt upon the tombs of old Christians were in all places ordinary) with his name inscribed, and the letter side of it turned to the stone. He (King Arthur) was then honoured with a sumptuous monument, and afterwards the sculls of him and his wife Guinevere were taken out (to remain as separate relics and spectacles) by Edward LongShanks and Eleanor." But notwithstanding the useful and apposite inscription on the leaden cross, " Hie jacet sepultus inclytus rex Arthurus in insula Avalonia"; or as it is otherwise more epigrammatically given, " Hie jacet Arthurus, Rex quondam, Rexque futurus"-

"His Epitaph recordeth so certaine

Here lieth King Arthur that shall raigne againe;"

it is hardly necessary to add that there is almost every reason to believe that this extraordinary " find " could have been nothing but a pious fraud, in majorem monasterii gloriam. If the truth be not established, however, it has been incorporated into many chronicles as genuine history. Bale, in his Actes of English Votaries, bears testimony in these words: "In Avallon, annus 1191, there found they the fleshe bothe of Arthur and of hys wyfe Guenever turned all into duste, wythin theyr coffins of strong oke, the bones only remaynge. A monke of the same Abbeye, standing and beholding the fine broydinges of the womman's heare as yellow as golde there still to remayne: as a man ravyshed, or more than halfe from hys wyttes, he leaped into the graffe, XV fete depe, to have caughte them sodenlye. But he fayled of hys purpose. For so soon as they were touched they fell all to powder." The reference to the depth of the grave reminds us that Stow, in his Chronicle, declares that King Arthur was buried sixteen feet underground to prevent the Saxons offering any indignity to his corpse, "which Almighty God, for the sins of the Britons, afterwards permitted," he disappointingly concludes.

Camden's account of the discovery is in these words: "When Henry II, King of England, had learned from the songs of the British bards, that Arthur, the most noble hero of the Britons, whose courage had so often shattered the Saxons, was buried at Glessenbury between two pyramids, he order 'd search to be made for the body; and they had scarce digg'd seven feet deep, but they light upon a cross 'd stone (cippus) or a stone in the back part whereof was fastened a rude leaden cross, something broad. This being pulled out, appeared to have an inscription upon it, and under it, almost nine foot deep, deposited the bones of the famous Arthur. The letters have a sort of barbarous and Gothic appearance, and are a plain evidence of the barbarity of the age, which was involved in a fatal sort of mist, that no one was found to celebrate the name of King Arthur." The most detailed account of all is given in Joseph Ritson's scholarly work on King Arthur, and the famous antiquary's outspoken comments on the records "and other legendary rhodomontades" of the monks of Glastonbury can be read with amusement as well as with profit. It is a sufficiently remarkable fact that none of the chroniclers agree in their details, and Matthew Paris dis~ tinctly declares that the letters inscribed upon the tomb could "in no wise be read on account of too much barbarism and deformity." Antiquary Leland was sceptical as to the coffin, and William of Malmesbury (1143) said "The sepulchre of Arthur was never seen "; but, despite all contradictions and doubts, the discovery seems to have been generally accepted as genuine, while for many reasons it was gratifying to the people of that and subsequent ages. Caxton would have regarded it as " most execrable infidelity " to have had a doubt upon the subject. At Glastonbury we indubitably seem to get nearer the real Arthur than we are able to do in any of the other localities mentioned by Geoffrey and the later chroniclers. Whether he was the monarch described in the romances or a semi-barbarous chieftain leading the Britons to a final, though only temporary, victory against the Saxons, there remains the same likelihood of his connection with the first Abbey raised in the land.

On the authority of Gildas, we learn that when the Abbot brought about peace between Arthur and Melvas, both kings made oath never to violate the holy place, and both kings gave the Abbot much territory in token of their gratitude. If, however, it is hard to reconcile the death of King Arthur with Merlin's prophecy, it is harder still to account for the discovery of his bones and his grave in face of the ancient triad which declared his grave to be unknown, and remembering which Tennyson related

"His grave should be a mystery

From all men, like his birth;"

while the older poet tells how he "raygnes in faerie." There was, however, a substantial reason for the finding of King Arthur's tomb by Henry of Blois, for at that time the revenues brought by pilgrims to the shrine were not sufficient to provide funds for the building. The contest between Wells and Glastonbury had also begun, and the discovery of the bones of a saint was one of the surest methods of obtaining an advantage. According to Stow's Chronicle, the body was found "not enclosed within a tomb of stone, but within a great tree made hollow like a trough, the which being digged upon and opened, therein were found the bones of Arthur, which were of a marvellous bigness." This circumstantial evidence seems almost irresistible, and no doubt there was a conscientious belief in the discovery at the time it was reported to have been made. Stow has further details to give on the authority of Giraldus Cambriensis, "a learned man that then lived, who reporteth to have heard of the Abbot of Glastonbury that the shin-bone of Arthur being set up by the leg of a very tall man, came above his knee by three fingers. The skull of his head was of a wonderful bigness; in which head there appeared the points of ten wounds, or more, all which were grown in one seam, except only that whereof he died, which being greater than the other, appeared very plain." Such, then, are the records of this wondrous discovery.

Modern Glastonbury has its museum in which may be seen some pottery from "King Arthur's Palace at Wedmore," and a thirteenth or fourteenth century representation on the side of a mirror case of Queen Guinevere deserting with Sir Lancelot, the only two relics, I believe, which in any way recall the connection of King Arthur with the place. There are evidences of the antiquity of the Abbey in abundance; though pilgrims' staffs, leather bottles, palls, grace cups, roods, "counters" made by the monks to serve as coin, and even the reliquary containing a small piece of bone supposed to be of St. Paulinus, sent or left by St. Augustine himself for the purpose of establishing the modified form of the Benedictine rule, do not quite take us back to the sixth century. Though the actual date of King Arthur's death is not known, and though his age is variously given from just over fifty to passing ninety, and though there is no consensus of opinion as to the length of his reign, we never hear of him at a later date than 604; and unfortunately all the Glastonbury relics take us back at most to the tenth century. Yet enthusiastic Drayton might well be carried away with the theme with which Glastonbury supplied him; and remembering the marvels of its past and the splendour of its aspect in his own day, he asked what place was comparable with the "three times famous isle?"

"To whom didst thou commit that monument to

keep,

When not great Arthur's tomb, nor holy Joseph's grave

From sacrilege had power their holy bones to save? "

This is one of the insoluble mysteries. The remains of Arthur and Guinevere are stated to have had noble burial by King Henry's command in "a fair tomb of marble," and the cross of lead bearing the original inscription was placed in the church treasury. At the suppression of the monasteries it is assumed that all the tombs and monuments shared one fate. Edward I and his queen visited Glastonbury in 1278, and after seeing the shrine, fixed their signets upon the separate " chests " in which the dust was deposited. Within the sepulchre they placed a solemn written record of what they had seen, together with the names of the principal witnesses. King Edward is also said to have had Arthur's crowns and jewels rendered to him. He and his queen were satisfied that they had gazed upon " the bones of the most noble Arthur "; and theirs were the last eyes to see the remains, false or true. The historian Speed, in indignant strain, tells of the doom that befell the Abbey in Henry VIII's days, when "this noble monument, among the fatal overthrows of infinite more, was altogether razed by those whose over-hasty actions and too forward zeal in these behalfs hath left us the want of many truths, and cause to wish that some of their employments had been better spent." Whatever sign of King Arthur's tomb, real or pretended, had existed, thus vanished for ever, and the prophesied mystery of his grave became fulfilled.

All that now remains in association with his name, and his final acts, and his uncomprehended fate, is the Abbey, surpassingly beautiful in ruin, founded in times faded almost from the recollections of a race; it is itself half mystery and half monument. The stateliest of its chambers still bears the name of St. Joseph's Chapel, and itself with its delicate tracery, its exquisitely designed windows, its carved pillars, is like a fairy tale in stone. The little church built with wattles from the marsh became the church triumphant and the church supremely beautiful in after-time. When the second Henry visited it the already venerable Abbey was a pile of architectural wonders and magnificence, thanks to the labours of Abbot Harlewinus. It was he who designed and erected that veritable gem of architecture, gorgeously ornamented and finished in classic grace, which serves as memorial to the first Christian saint in England. "Imagination cannot realise," says one chronicler, "how grand and beautiful must have been the view from St. Joseph's Chapel through its long-drawn fretted aisles up to the high altar with its four corners, symbolising the Gospel to be spread through the four quarters of the world." The matchless temple was over a hundred feet longer than Westminster Abbey; and its spaciousness was only equalled by its riches. Lofty mullioned windows rose nearly to the vaulting, richly dight and casting a dim religious light; and the profuse decorations of the walls took the form of running patterns of foliage, while vivid paintings of the sun and stars gave colour and animation to the cold stone. Little wonder that the gorgeous Abbey in all its loveliness and noble proportions was deemed a fitting resting-place for kings and saints. Claiming St. Joseph as its founder, it was almost in natural sequence that it should make claim to be the shrine of the last and greatest of the Christian kings, the Arthur whom Geoffrey of Monmouth had made renowned "the most king and knight of the world, and most loved of the fellowship of noble knights, and by turn they were all upholden." It was to Glastonbury that the "Bishop of Canterbury " fled, and took his goods, and " lived in poverty and in holy prayers " when the war with Mordred broke out. To this hermit came Sir Bedivere, and found him by a tomb new-graven. "Sir," said Sir Bedivere, "what man is there interred that ye pray so fast for?" "Fair son," said the hermit, "I wot not verily, but by deeming. But this night, at midnight, here came a number of ladies, and brought hither a dead corpse, and prayed me to bury him; and here they offered an hundred tapers, and gave me an hundred besants." "Alas," said Sir Bedivere, "that was my lord King Arthur, that here lieth buried in this chapel !" Then Sir Bedivere swooned, and when he awoke prayed that he might abide there henceforth and live with fasting and prayers. " Far from hence will I never go," said he, "by my will, but all the days of my life to pray for my lord Arthur."

Glastonbury to-day, amid all its ruin, spoliation" and change, hints everywhere of the glory of its past. The charm of it lingers though the excellence of it has vanished. In its stillness and seclusion it retains an old-world air of beauty and of simplicity; time which has overthrown so much has tainted nought. Tower, wall, and roof mingle their grey and brown and red in the peaceful valley which the sparkling rivulets water and entwine as with silver threads. The sheltered gardens upon which the sunlight falls luxurious are bounteous as ever they were, and one might almost expect to see in the shadowy consecrated places cowled and hooded monks pacing noiselessly, their eyes intent upon black-letter missals, or uplifted to behold the magic and splendour of hill and dale. The winding road has felt the pressure of many pilgrims' feet; at the vesper hour the weary fervent throng gathered about the Abbey doors; and through the spacious aisles, cool and shadowy, or stained with the rich colours carried by slanting beams through the painted windows, the holy brothers moved in slow and solemn procession, their voices subdued in chant, the air they breathed sweet with incense. Easily imagined is the hallowed aspect of the lofty fane when the last rays of the sun shot redly within, suffused the altar in a crimson haze, and glowed upon the burnished ornaments and the carvings of veined marble and whitest stone; when the darkness gathered hauntingly, and one by one the tapers were lit, while the people were hushed and expectant, and the monks bowed themselves in adoration. Holy relics would show dimly in their places, rod and crucifix stand out dark against the walls, the royal tombs be covered as with a pall, and a mysterious awe descend upon the worshippers in the temple. Outside the world would be hushed, even as it is hushed today when the pilgrim stands amid the broken walls of St. Joseph's Chapel, or treads the thick green turf between crumbling vestibule and arch. Truly Glastonbury was an isle of rest.

King Arthur had fought against the pagan horde and "upheld the Christ." Glastonbury withstood the heathen, and boasted to the last of never having fallen into sacrilegious hands. It was Christian always the Church of martyrs like Indractus, of saints like Cuthbert, Patrick, David, and Dunstan, and of kings like Ina, Edmund, and Arthur. The massive walls nobly withstood the assault of time, and the ruins of to-day are the work of the iconoclast, due to desecration and not d^oay. The remnants are pathetic in their significance; the scene of mutilated beauty is mournful beyond expression. Yet the beauty remains, though it is not the beauty of spirituality and life, but of the ethereality of death. As we gaze we are with a bygone age and generation, and that age seems to imbue our thought and tinge our reflections. Everywhere may be seen mementoes; all sounds are like echoes, faint and far; all sights are dim with haze. Glastonbury is for retrospection. The air is full of traditions; its history deals with phantoms and its opening page is of myths.

Take your stand on Wearyall Hill, and brood awhile upon the surroundings. You thrill to think that here St. Joseph might have paused; that here, where lies a' stone engraved with J. A., his withered pilgrim's staff might have burst into bloom. A few young trees are bending to the wind; down below the old city stretches away in grey lines, and there are some tumble-down houses of antique appearance produced by the old rafters and rough stone of which they are constructed. Bright and cheerful are many lattice windows which twinkle out between the heavy time-scarred mullions wrought long and long ago. Yonder is Tor Hill, and the great green valley spreads southward, strewn with trees thickly, and ending only where the dipping horizon meets it. The two Glastonbury towers are standing out boldly, almost as if defiant; the red roofs of the city cluster below; and, set deeply and immutably among aged and dark green trees, are the rent but erect walls of the first Christian Abbey.

Or retrace your steps, and after passing the Abbey bounds, mount the steep Tor and stand by the Tower which alone escaped the shattering force of earthquake. From this summit the view of the landscape is far and good. Scarcely can you realise that once the salt waves lapped this steep eminence, but the sand and shells mixed and embedded in the soil have graven that event more legibly than the pen of man could have inscribed it. It is sunset sunset over the Avalonian isle. The day has been calm and grey, and the end is to be calm, autumnal, subdued. There is one long quivering stretch of cardinal in the west, but elsewhere the sky is wonderfully sombre, yet exquisitely soft and pearly clear. The furthermost limit of the vale fast becomes invisible, fading imperceptibly, apparently merging into the sky as it becomes a pure deep blue. Here and there a purple peak of the range of hills running seaward rises sharply and pierces the thin gauzy clouds which the wind brings up. The white road gleams below, wholly deserted, yet fancy may conjure up spectres gliding at nightfall along the once hallowed way to the shrine. On this steep hill, alone, cloud-high, you feel that the silence is mystical, and wonder if the sleeping city with its ghosts and traditions is like the fabled cities of enchanters which rise at night without foundation and dissolve like mist in the earliest light of morning.