|

|

The Age of Chivalry, or Legends of King Arthur

CHAPTER III.

ARTHUR.

WE shall begin our history of King Arthur by giving those particulars of his life which appear to rest on historical evidence; and then proceed to record those legends concerning him which form the earliest portion of British literature.

[See: King Arthur and his Knights By Maude L. Radford]

[See: Tales of the Round Table. Edited by Andrew Lang]

[See: The Story of the Champions of the Round Table]

[See: Four Arthurian Romances by Chretien DeTroyes]

[See: Idylls of the King by Tennyson. Illustrated by Gustave Doré]

[See: Arthur - A Short Sketch of his Life and History]

[See: In The Court of King Arthur By Samuel E. Lowe]

[See: The Legends of King Arthur And His Knights By Sir James Knowles]

Arthur was a prince of the tribe of Britons called Silures, whose country was South Wales,– the son of Uther, named Pendragon, a title given to an elective sovereign, paramount over the many kings of Britain. He appears to have commenced his martial career about the year 500, and was raised to the Pendragonship about ten years later. He is said to have gained twelve victories over the Saxons. The most important of them was that of Badon, by some supposed to be Bath, by others Berkshire. This was the last of his battles with the Saxons, and checked their progress so effectually that Arthur experienced no more annoyance from them, and reigned in peace, until the revolt of his nephew Modred, twenty years later, which led to the fatal battle of Camlan, in Cornwall, in 542. Modred was slain, and Arthur, mortally wounded, was conveyed by sea to Glastonbury, where he died, and was buried.

[See: References to the Silures]

[See: Short History of Wales, by Owen M. Edwards]

Giraldus Cambrensis

Tradition preserved the memory of the place of his interment within the abbey, as we are told by Giraldus Cambrensis, who was present when the grave was opened by command of Henry II. in 1150, and saw the bones and sword of the monarch, and a leaden cross let into his tombstone, with the inscription in rude Roman letters, “Here lies buried the famous King Arthur, in the island Avolonia.” This story has been elegantly versified by Warton.

[See: Two Accounts of the Discovery and Exhumation of King Arthur's Body

[See: Baldwin's Itinerary Through Wales by Giraldus Cambrensis

[See: Description of Wales by Giraldus Cambrensis

A popular traditional belief was long entertained among the Britons that Arthur was not dead, but had been carried off to be healed of his wounds in Fairy–land, and that he would reappear to avenge his countrymen, and reinstate them in the sovereignty of Britain. In Wharton’s Ode a bard relates to King Henry the traditional story of Arthur’s death, and closes with these lines:–

“Yet in vain a paynim foe

Armed with fate the mighty blow;

For when he fell, the Elfin queen,

All in secret and unseen,

O’er the fainting hero threw

Her mantle of ambrosial blue,

And bade her spirits bear him far,

In Merlin’s agate-axled car,

To her green isle’s enamelled steep,

Far in the navel of the deep.

O’er his wounds she sprinkled dew

From flowers that in Arabia grew.There he reigns a mighty king,

Thence to Britain shall return,

If right prophetic rolls I learn,

Borne on victory’s spreading plume,

His ancient sceptre to resume,

His knightly table to restore,

And brave the tournaments of yore.”

After this narration another bard came forward, who recited a different story:–

“When Arthur bowed his haughty crest,

No princess veiled in azure vest

Snatched him, by Merlin’s powerful spell,

In groves of golden bliss to dwell;

But when he fell, with winged speed,

His champions, on a milk-white steed,

From the battle’s hurricane

Bore him to Joseph’s towered fane,[2]In the fair vale of Avalon;

There, with chanted orison

And the long blaze of tapers clear,

The stoled fathers met the bier;

Through the dim aisles, in order dread

Of martial woe, the chief they led,

And deep entombed in holy ground,

Before the altar’s solemn bound.”

[See: Wharton’s The Grave of King Arthur]

[2] Glastonbury Abbey, said to be founded by Joseph of Arimathea, in a spot anciently called the island or valley of Avalonia.

[See: The Ballad of Glastonbury, by Henry Alford]

Tennyson, in his Palace of Art, alludes to the legend of Arthur’s rescue by the Fairy queen, thus:–

“Or mythic Uther’s deeply wounded son,

In some fair space of sloping greens,

Lay dozing in the vale of Avalon,

And watched by weeping queens.”

[See: The Palace of Art by Alfred Lord Tennyson]

It must not be concealed, that the very existence of Arthur has been denied by some. Milton says of him: “As to Arthur, more renowned in songs and romances than in true stories, who he was, and whether ever any such reigned in Britain, hath been doubted heretofore, and may again, with good reason.” Modern critics, however, admit that there was a prince of this name, and find proof of it in the frequent mention of him in the writings of the Welsh bards. But the Arthur of romance, according to Mr. Owen, a Welsh scholar and antiquarian, is a mythological person. “Arthur,” he says, “is the Great Bear, as the name literally implies (Arctos, Arcturus), and perhaps this constellation, being so near the pole, and visibly describing a circle in a small space, is the origin of the famous Round Table.”

Let us now turn to the history of King Arthur, as recorded by the romantic chroniclers.

[See: The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle]

[See: Arthurian Chronicles: Roman de Brut By Wace]

[See: Brut, by Layamon]

Constans, king of Britain, had three sons, Moines, Ambrosius, otherwise called Uther, and Pendragon. Moines, soon after his accession to the crown, was vanquished by the Saxons, in consequence of the treachery of his seneschal, Vortigern, and growing unpopular through misfortune, he was killed by his subjects, and the traitor Vortigern chosen in his place.

Vortigern was soon after defeated in a great battle by Uther and Pendragon, the surviving brothers of Moines, and Pendragon ascended the throne.

This prince had great confidence in the wisdom of Merlin, and made him his chief adviser. About this time a dreadful war arose between the Saxons and Britons. Merlin obliged the royal brothers to swear fidelity to each other, but predicted that one of them must fall in the first battle. The Saxons were routed, and Pendragon, being slain, was succeeded by Uther, who now assumed, in addition to his own name, the appellation of Pendragon.

Merlin still continued a favorite counsellor. At the request of Uther, he transported by magic art enormous stones from Ireland, to form the sepulchre of Pendragon. These stones constitute the monument now called Stonehenge, on Salisbury Plain.

Merlin next proceeded to Carlisle to prepare the Round Table, at which he seated an assemblage of the great nobles of the country. The companions admitted to this high order were bound by oath to assist each other at the hazard of their own lives, to attempt singly the most perilous adventures, to lead, when necessary, a life of monastic solitude, to fly to arms at the first summons, and never to retire from battle till they had defeated the enemy, unless night intervened and separated the combatants.

Soon after this institution, the king invited all his barons to the celebration of a great festival, which he proposed holding annually at Carlisle.

As the knights had obtained the sovereign’s permission to bring their ladies along with them, the beautiful Igerne accompanied her husband, Gerlois, Duke of Tintadiel, to one of these anniversaries. The king became deeply enamored of the Duchess, and disclosed his passion; but Igerne repelled his advances, and revealed his solicitations to her husband. On hearing this, the Duke instantly removed from court with Igerne, and without taking leave of Uther. The king complained to his council of this want of duty, and they decided that the Duke should be summoned to court, and, if refractory, should be treated as a rebel. As he refused to obey the citation, the king carried war into the estates of his vassal, and besieged him in the strong castle of Tintadiel. Merlin transformed the king into the likeness of Gerlois, and enabled him to have many stolen interviews with Igerne. At length the Duke was killed in battle, and the king espoused Igerne.

From this union sprang Arthur, who succeeded his father, Uther, upon the throne.

ARTHUR CHOSEN KING.

Arthur, though only fifteen years old at his father’s death, was elected king, at a general meeting of the nobles. It was not done without opposition, for there were many ambitious competitors; but Bishop Brice, a person of great sanctity, on Christmas eve addressed the assembly, and represented that it would well become them, at that solemn season, to put up their prayers for some token which should manifest the intentions of Providence respecting their future sovereign. This was done, and with such success, that the service was scarcely ended, when a miraculous stone was discovered, before the church door, and in the stone was firmly fixed a sword, with the following words engraven on its hilt:–

“I am hight Escalibore,

Unto a king fair tresore.”

Bishop Brice, after exhorting the assembly to offer up their thanksgivings for this signal miracle, proposed a law, that whoever should be able to draw out the sword from the stone, should be acknowledged as sovereign of the Britons; and his proposal was decreed by general acclamation. The tributary kings of Uther, and the most famous knights, successively put their strength to the proof, but the miraculous sword resisted all their efforts. It stood till Candlemas; it stood till Easter, and till Pentecost, when the best knights in the kingdom usually assembled for the annual tournament. Arthur, who was at that time serving in the capacity of squire to his foster–brother, Sir Kay, attended his master to the lists. Sir Kay fought with great valor and success, but had the misfortune to break his sword, and sent Arthur to his mother for a new one. Arthur hastened home, but did not find the lady; but having observed near the church a sword sticking in a stone, he galloped to the place, drew out the sword with great ease, and delivered it to his master. Sir Kay would willingly have assumed to himself the distinction conferred by the possession of the sword; but when, to confirm the doubters, the sword was replaced in the stone, he was utterly unable to withdraw it, and it would yield a second time to no hand but Arthur’s. Thus decisively pointed out by Heaven as their king, Arthur was by general consent proclaimed such, and an early day appointed for his solemn coronation.

Immediately after his election to the crown, Arthur found himself opposed by eleven kings and one duke, who with a vast army were actually encamped in the forest of Rockingham. By Merlin’s advice Arthur sent an embassy to Brittany to solicit aid of King Ban and King Bohort, two of the best knights in the world. They accepted the call, and with a powerful army crossed the sea, landing at Portsmouth, where they were received with great rejoicing. The rebel kings were still superior in numbers; but Merlin by a powerful enchantment, caused all their tents to fall down at once, and in the confusion Arthur with his allies fell upon them and totally routed them.

After defeating the rebels, Arthur took the field against the Saxons. As they were too strong for him unaided, he sent an embassy to Armorica, beseeching the assistance of Hoel, who soon after brought over an army to his aid. The two kings joined their forces, and sought the enemy, whom they met, and both sides prepared for a decisive engagement. “Arthur himself,” as Geoffrey of Monmouth relates, “dressed in a breastplate worthy of so great a king, places on his head a golden helmet engraved with the semblance of a dragon. Over his shoulders he throws his shield called Priwen, on which a picture of the Holy Virgin constantly recalled her to his memory. Girt with Caliburn, a most excellent sword, and fabricated in the isle of Avalon, he graces his right hand with the lance named Ron. This was a long and broad spear, well contrived for slaughter.” After a severe conflict, Arthur, calling on the name of the Virgin, rushes into the midst of his enemies, and destroys multitudes of them with the formidable Caliburn, and puts the rest to flight. Hoel, being detained by sickness, took no part in this battle.

This is called the victory of Mount Badon, and, however disguised by fable, it is regarded by historians as a real event.

The feats performed by Arthur at the battle of Badon Mount are thus celebrated in Drayton’s verse:–

“They sung how he himself at Badon bore, that day,

When at the glorious goal his British scepter lay;

Two dais together how the battle stronglie stood;

Pendragon’s worthie son, who waded there in blood,

Three hundred Saxons slew with his owne valiant hand.”

--Song IV.

MERLIN.

“-The most famous man of all those times,

Merlin, who knew the range of all their arts,

Had built the King his havens, ships and halls,

Was also Bard, and knew the starry heavens;

The people called him wizard.”

--TENNYSON.

[See: Merlin The Enchanter]

[See: The Prophecy Of Merlin By Anne Bannerman

Now Merlin, of whom we have already heard somewhat and shall hear more, was the son of no mortal father, but of an Incubus, one of a class of beings not absolutely wicked, but far from good, who inhabit the regions of the air. Merlin’s mother was a virtuous young woman, who, on the birth of her son, intrusted him to a priest, who hurried him to the baptismal fount, and so saved him from sharing the lot of his father, though he retained many marks of his unearthly origin.

[See: Merlin references in The Origins Of Folklore]

[See: Merlin references in The Magical Control of Rain]

At this time Vortigern reigned in Britain. He was a usurper, who had caused the death of his sovereign, Moines, and driven the two brothers of the late king, whose names were Uther and Pendragon, into banishment. Vortigern, who lived in constant fear of the return of the rightful heirs of the kingdom, began to erect a strong tower for defence. The edifice, when brought by the workmen to a certain height, three times fell to the ground, without any apparent cause. The king consulted his astrologers on this wonderful event, and learned from them that it would be necessary to bathe the cornerstone of the foundation with the blood of a child born without a mortal father.

In search of such an infant, Vortigern sent his messengers all over the kingdom, and they by accident discovered Merlin, whose lineage seemed to point him out as the individual wanted. They took him to the king; but Merlin, young as he was, explained to the king the absurdity of attempting to rescue the fabric by such means, for he told him the true cause of the instability of the tower was its being placed over the den of two immense dragons, whose combats shook the earth above them. The king ordered his workmen to dig beneath the tower, and when they had done so they discovered two enormous serpents, the one white as milk, the other red as fire. The multitude looked on with amazement, till the serpents, slowly rising from their den, and expanding their enormous folds, began the combat, when every one fled in terror, except Merlin, who stood by clapping his hands and cheering on the conflict. The red dragon was slain, and the white one, gliding through a cleft in the rock, disappeared.

These animals typified, as Merlin afterwards explained, the invasion of Uther and Pendragon, the rightful princes, who soon after landed with a great army. Vortigern was defeated, and afterwards burned alive in the castle he had taken such pains to construct. On the death of Vortigern, Pendragon ascended the throne. Merlin became his chief adviser, and often assisted the king by his magical arts. Among other endowments, he had the power to transform himself into any shape he pleased. At one time he appeared as a dwarf, at others as a damsel, a page, or even a greyhound or a stag. This faculty he often employed for the service of the king, and sometimes also for the diversion of the court and the sovereign.

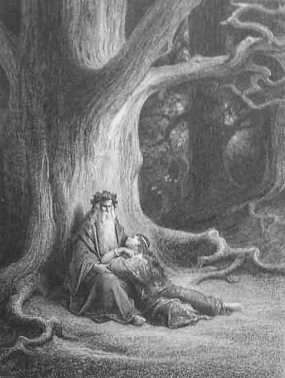

Merlin continued to be a favorite counsellor through the reigns of Pendragon, Uther, and Arthur, and at last disappeared from view, and was no more found among men, through the treachery of his mistress, Viviane, the Fairy, which happened in this wise.

Merlin, having become enamored of the fair Viviane, the Lady of the Lake, was weak enough to impart to her various important secrets of his art, being impelled by a fatal destiny, of which he was at the same time fully aware. The lady, however, was not content with his devotion, unbounded as it seems to have been, but “cast about,” the Romance tells us, how she might “detain him for evermore,” and one day addressed him in these terms: “Sir, I would that we should make a fair place and a suitable, so contrived by art and by cunning that it might never be undone, and that you and I should be there in joy and solace.” “My lady,” said Merlin, “I will do all this.” “Sir,” said she, “I would not have you do it, but you shall teach me, and I will do it, and then it will be more to my mind.” “I grant you this,” said Merlin. Then he began to devise, and the damsel put it all in writing. And when he had devised the whole, then had the damsel full great joy, and showed him greater semblance of love than she had ever before made, and they sojourned together a long while. At length it fell out that, as they were going one day in hand through the forest of Breceliande, they found a bush of white–thorn, which was laden with flowers; and they seated themselves, under the shade of this white–thorn, upon the grass, and Merlin laid his head upon the damsel’s lap, and fell asleep. Then the damsel rose, and made a ring with her wimple round the bush, and round Merlin, and began her enchantments, such as he himself had taught her; and nine times she made the ring, and nine times she made the enchantment, and then she went and sat down by him, and placed his head again upon her lap. And when he awoke, and looked round him, it seemed to him that he was enclosed in the strongest tower in the world, and laid upon a fair bed. Then said he to the dame: “My lady, you have deceived me, unless you abide with me, for no one hath power to unmake this tower but you alone.” She then promised that she would be often there, and in this she held her covenant with him. And Merlin never went out of that tower where his Mistress Viviane had enclosed him; but she entered and went out again when she listed.

After this event Merlin was never more known to hold converse with any mortal but Viviane, except on one occasion. Arthur, having for some time missed him from his court, sent several of his knights in search of him, and among the number Sir Gawain, who met with a very unpleasant adventure while engaged in this quest. Happening to pass a damsel on his road, and neglecting to salute her, she revenged herself for his incivility by transforming him into a hideous dwarf. He was bewailing aloud his evil fortune as he went through the forest of Breceliande, when suddenly he heard the voice of one groaning on his right hand; and, looking that way, he could see nothing save a kind of smoke, which seemed like air, and through which he could not pass.

[See: Sir Gawayne and The

Green Knight

An Alliterative Romance Poem]

Merlins Tower, from A Connecticut Yankee By Mark Twain

Merlin then addressed him from out the smoke, and told him by what misadventure he was imprisoned there. “Ah, sir!” he added, “you will never see me more, and that grieves me, but I cannot remedy it; I shall never more speak to you, nor to any other person, save only my mistress. But do thou hasten to King Arthur, and charge him from me to undertake, without delay, the quest of the Sacred Graal. The knight is already born, and has received knighthood at his hands, who is destined to accomplish this quest.” And after this he comforted Gawain under his transformation, assuring him that he should speedily be disenchanted; and he predicted to him that he should find the king at Carduel, in Wales, on his return, and that all the other knights who had been on like quest would arrive there the same day as himself. And all this came to pass as Merlin had said.

Merlin is frequently introduced in the tales of chivalry, but it is chiefly on great occasions, and at a period subsequent to his death, or magical disappearance. In the romantic poems of Italy, and in Spenser, Merlin is chiefly represented as a magical artist. Spenser represents him as the artificer of the impenetrable shield and other armor of Prince Arthur (Faery Queene, Book I., Canton vii.), and of a mirror, in which a damsel viewed her lover’s shade. The Fountain of Love, in the Orlando Innamorato, is described as his work; and in the poem of Ariosto we are told of a hall adorned with prophetic paintings, which demons had executed in a single night, under the direction of Merlin.

The following legend is from Spenser’s Faery Queene (Book III., Canto iii.):–

CAER–MERDIN, OR CAERMARTHEN (IN WALES), MERLIN’S TOWER, AND THE IMPRISONED FIENDS.

Forthwith themselves disguising both, in straunge

And base attire, that none might them bewray,

To Maridunum, that is now by chaunge

Of name Caer-Merdin called, they took their way:

There the wise Merlin, whylome wont (they say)

To make his wonne, low underneath the ground

In a deep delve, far from the view of day,

That of no living wight he mote be found,

Whenso he counselled with his sprights encompassed round.And if thou ever happen that same way

To travel, go to see that dreadful place;

It is a hideous hollow cave (they say)

Under a rock that lies a little space,

From the swift Barry, tombling down apace

Amongst the woody hills of Dynevor;

But dare not thou, I charge, in any case,

To enter into that same baleful bower,

For fear the cruel fiends should thee unwares devour.But standing high aloft, low lay thine ear,

And there such ghastly noise of iron chains

And brazen cauldrons thou shalt rumbling hear,

Which thousand sprites with long enduring pains

Do toss, that it will stun thy feeble brains;

And oftentimes great groans, and grievous stounds,

When too huge toil and labor them constrains;

And oftentimes loud strokes and ringing sounds

From under that deep rock most horribly rebounds.The cause some say is this. A little while

Before that Merlin died, he did intend

A brazen wall in compas to compile

About Caermerdin, and did it commend

Unto these sprites to bring to perfect end;

During which work the Lady of the Lake,

Whom long he loved, for him in haste did send;

Who, thereby forced his workmen to forsake,

Them bound till his return their labor not to slack.In the meantime, through that false lady’s train,

He was surprised, and buried under beare,[3]

Ne ever to his work returned again;

Natheless those fiends may not their work forbear,

So greatly his commandement they fear;

But there do toil and travail day and night,

Until that brazen wall they up do rear.

For Merlin had in magic more insight

Than ever him before or after living wight.

[3] Buried under beare. Buried under something which enclosed him like a coffin or bier.

GUENEVER.

“Leodogran, the King of Cameliard,

Had one fair daughter, and none other child,

And she was fairest of all flesh on earth,

Guenevere, and in her his one delight.”

From Idylls of the King by Tennyson.

Merlin had planned for Arthur a marriage with the daughter of King Laodegan[4] of Carmalide. By his advice Arthur paid a visit to the court of that sovereign, attended only by Merlin and by thirty–nine knights whom the magician had selected for that service. On their arrival they found Laodegan and his peers sitting in council, endeavoring, but with small prospect of success, to devise means for resisting the impending attack of Ryence, King of Ireland, who, with fifteen tributary kings and an almost innumerable army, had nearly surrounded the city.

Merlin, who acted as leader of the band of British knights, announced them as strangers, who came to offer the king their services in his wars; but under the express condition that they should be at liberty to conceal their names and quality until they should think proper to divulge them. These terms were thought very strange, but were thankfully accepted, and the strangers, after taking the usual oath to the king, retired to the lodging which Merlin had prepared for them.

[4] The spelling of these proper names is very often only a matter of taste. I think, however, Leodogran and Guenevere are less common than Laodegan and Guenever.

[See: The Defence of Guenevere, by William Morris]

A few days after this, the enemy, regardless of a truce into which they had entered with King Laodegan, suddenly issued from their camp and made an attempt to surprise the city. Cleodalis, the king’s general, assembled the royal forces with all possible despatch. Arthur and his companions also flew to arms, and Merlin appeared at their head, bearing a standard on which was emblazoned a terrific dragon.

Merlin advanced to the gate, and commanded the porter to open it, which the porter refused to do, without the king’s order. Merlin thereupon took up the gate, with all its appurtenances of locks, bars, and bolts, and directed his troop to pass through, after which he replaced it in perfect order. He then set spurs to his horse, and dashed, at the head of the little troop, into a body of two thousand Pagans. The disparity of numbers being so enormous, Merlin cast a spell upon the enemy, so as to prevent their seeing the small number of their assailants; notwithstanding which the British knights were hard pressed. But the people of the city, who saw from the walls this unequal contest, were ashamed of leaving the small body of strangers to their fate, so they opened the gate and sallied forth. The numbers were now more nearly equal, and Merlin revoked his spell, so that the two armies encountered on fair terms. Where Arthur, Ban, Bohort, and the rest fought, the king’s army had the advantage; but in another part of the field the king himself was surrounded and carried off by the enemy. This sad sight was seen by Guenever, the fair daughter of the king, who stood on the city wall and looked at the battle. She was in dreadful distress, tore her hair, and swooned away.

But Merlin, aware of what passed in every part of the field, suddenly collected his knights, led them out of the battle, intercepted the passage of the party who were carrying away the king, charged them with irresistible impetuosity, cut in pieces or dispersed the whole escort, and rescued the king. In the fight Arthur encountered Caulang, a giant fifteen feet high, and the fair Guenever, who already began to feel a strong interest in the handsome young stranger, trembled for the issue of the contest. But Arthur, dealing a dreadful blow on the shoulder of the monster, cut through his neck so that his head hung over on one side, and in this condition his horse carried him about the field, to the great horror and dismay of the Pagans. Guenever could not refrain from expressing aloud her wish that the gentle knight, who dealt with giants so dexterously, were destined to become her husband, and the wish was echoed by her attendants. The enemy soon turned their backs, and fled with precipitation, closely pursued by Laodegan and his allies.

After the battle Arthur was disarmed and conducted to the bath by the Princess Guenever, while his friends were attended by the other ladies of the court. After the bath the knights were conducted to a magnificent entertainment, at which they were diligently served by the same fair attendants. Laodegan, more and more anxious to know the name and quality of his generous deliverers, and occasionally forming a secret wish that the chief of his guests might be captivated by the charms of his daughter, appeared silent and pensive, and was scarcely roused from his reverie by the banter of his courtiers. Arthur, having had an opportunity of explaining to Guenever his great esteem for her merit, was in the joy of his heart, and was still further delighted by hearing from Merlin the late exploits of Gawain at London, by means of which his immediate return to his dominions was rendered unnecessary, and he was left at liberty to protract his stay at the court of Laodegan. Every day contributed to increase the admiration of the whole court for the gallant strangers, and the passion of Guenever for their chief; and when at last Merlin announced to the king that the object of the visit of the party was to procure a bride for their leader, Laodegan at once presented Guenever to Arthur, telling him that, whatever might be his rank, his merit was sufficient to entitle him to the possession of the heiress of Carmalide. Arthur accepted the lady with the utmost gratitude, and Merlin then proceeded to satisfy the king of the rank of his son–in–law; upon which Laodegan, with all his barons, hastened to do homage to their lawful sovereign, the successor of Uther Pendragon. The fair Guenever was then solemnly betrothed to Arthur, and a magnificent festival was proclaimed, which lasted seven days. At the end of that time, the enemy appearing again with renewed force, it became necessary to resume military operations.[5]

[5] Guenever, the name of Arthur’s queen, also written Genievre and Geneuras, is familiar to all who are conversant with chivalric lore. It is to her adventures, and those of her true knight, Sir Launcelot, that Dante alludes in the beautiful episode of Francesca da Rimini.

We must now relate what took place at or near London while Arthur was absent from his capital. At this very time a band of young heroes were on their way to Arthur’s court, for the purpose of receiving knighthood from him. They were Gawain and his three brothers, nephews of Arthur, sons of King Lot, and Galachin, another nephew, son of King Nanters. King Lot had been one of the rebel chiefs whom Arthur had defeated, but he now hoped by means of the young men to be reconciled to his brother–in–law. He equipped his sons and his nephew with the utmost magnificence, giving them a splendid retinue of young men, sons of earls and barons, all mounted on the best horses, with complete suits of choice armor. They numbered in all seven hundred, but only nine had yet received the order of knighthood; the rest were candidates for that honor, and anxious to earn it by an early encounter with the enemy. Gawain, the leader, was a knight of wonderful strength; but what was most remarkable about him was that his strength was greater at certain hours of the day than at others. From nine o’clock till noon his strength was doubled, and so it was from three to even–song; for the rest of the time it was less remarkable, though at all times surpassing that of ordinary men.

After a march of three days they arrived in the vicinity of London, where they expected to find Arthur and his court; and very unexpectedly fell in with a large convoy belonging to the enemy, consisting of numerous carts and wagons, all loaded with provisions, and escorted by three thousand men, who had been collecting spoil from all the country round. A single charge from Gawain’s impetuous cavalry was sufficient to disperse the escort and to recover the convoy, which was instantly despatched to London. But before long a body of seven thousand fresh soldiers advanced to the attack of the five princes and their little army.

Gawain, singling out a chief named Choas, of gigantic size, began the battle by splitting him from the crown of the head to the breast. Galachin encountered King Sanagran, who was also very huge, and cut off his head. Agrivain and Gahariet also performed prodigies of valor. Thus they kept the great army of assailants at bay, though hard pressed, till of a sudden they perceived a strong body of the citizens advancing from London, where the convoy which had been recovered by Gawain had arrived, and informed the mayor and citizens of the danger of their deliverer. The arrival of the Londoners soon decided the contest. The enemy fled in all directions, and Gawain and his friends, escorted by the grateful citizens, entered London, and were received with acclamations.

After the great victory of Mount Badon, by which the Saxons were for the time effectually put down, Arthur turned his arms against the Scots and Picts, whom he routed at Lake Lomond, and compelled to sue for mercy. He then went to York to keep his Christmas, and employed himself in restoring the Christian churches which the Pagans had rifled and overthrown. The following summer he conquered Ireland, and then made a voyage with his fleet to Iceland, which he also subdued. The kings of Gothland and of the Orkneys came voluntarily and made their submission, promising to pay tribute. Then he returned to Britain, where, having established the kingdom, he dwelt twelve years in peace.

During this time, he invited over to him all persons whatsoever that were famous for valor in foreign nations, and augmented the number of his domestics, and introduced such politeness into his court as people of the remotest countries thought worthy of their imitation. So that there was not a nobleman who thought himself of any consideration unless his clothes and arms were made in the same fashion as those of Arthur’s knights.

Finding himself so powerful at home, Arthur began to form designs for extending his power abroad. So, having prepared his fleet, he first attempted Norway, that he might procure the crown of it for Lot, his sister’s husband. Arthur landed in Norway, fought a great battle with the king of that country, defeated him, and pursued the victory till he had reduced the whole country under his dominion, and established Lot upon the throne. Then Arthur made a voyage to Gaul and laid siege to the city of Paris. Gaul was at that time a Roman province, and governed by Flollo, the Tribune. When the siege of Paris had continued a month, and the people began to suffer from famine, Flollo challenged Arthur to single combat, proposing to decide the conquest in that way. Arthur gladly accepted the challenge, and slew his adversary in the contest, upon which the citizens surrendered the city to him.

After the victory Arthur divided his army into two parts, one of which he committed to the conduct of Hoel, whom he ordered to march into Aquitaine, while he with the other part should endeavor to subdue the other provinces. At the end of nine years, in which time all the parts of Gaul were entirely reduced, Arthur returned to Paris, where he kept his court, and calling an assembly of the clergy and people, established peace and the just administration of the laws in that kingdom. Then he bestowed Normandy upon Bedver, his butler, and the province of Andegavia upon Kay, his steward,[6] and several others upon his great men that attended him. And, having settled the peace of the cities and countries, he returned back in the beginning of spring to Britain.

[6] This name, in the French romances, is spelled Queux, which means head cook. This would seem to imply that it was a title, and not a name; yet the personage who bore it is never mentioned by any other. He is the chief, if not the only, comic character among the heroes of Arthur’s court. He is the Seneschal or Steward, his duties also embracing those of chief of the cooks. In the romances his general character is a compound of valor and buffoonery, always ready to fight, and generally getting the worst of the battle. He is also sarcastic and abusive in his remarks, by which he often gets into trouble. Yet Arthur seems to have an attachment to him, and often takes his advice, which is generally wrong.

THE CROWNING OF ARTHUR

Upon the approach of the feast of Pentecost, Arthur, the better to demonstrate his joy after such triumphant successes, and for the more solemn observation of that festival, and reconciling the minds of the princes that were now subject to him, resolved during that season to hold a magnificent court, to place the crown upon his head, and to invite all the kings and dukes under his subjection to the solemnity. And he pitched upon Caerleon, the City of Legions, as the proper place for his purpose. For, besides its great wealth above the other cities,[7] its situation upon the river Usk, near the Severn sea, was most pleasant and fit for so great a solemnity. For on one side it was washed by that noble river, so that the kings and princes from the countries beyond the seas might have the convenience of sailing up to it. On the other side the beauty of the meadows and groves, and magnificence of the royal palaces, with lofty gilded roofs that adorned it, made it even rival the grandeur of Rome. It was also famous for two churches, whereof one was adorned with a choir of virgins, who devoted themselves wholly to the service of God, and the other maintained a convent of priests. Besides, there was a college of two hundred philosophers, who, being learned in astronomy and the other arts, were diligent in observing the courses of the stars, and gave Arthur true predictions of the events that would happen. In this place, therefore, which afforded such delights, were preparations made for the ensuing festival.

[7] Several cities are allotted to King Arthur by the romance–writers. The principal are Caerleon, Camelot, and Carlisle.

Caerleon derives its name from its having been the station of one of the legions during the dominion of the Romans. It is called by Latin writers Urbs Legionum, the City of Legions,– the former word being rendered into Welsh by Caer, meaning city, and the latter contracted into lleon. The river Usk retains its name in modern geography, and there is a town or city of Caerleon upon it, though the city of Cardiff is thought to be the scene of Arthur’s court. Chester also bears the Welsh name of Caerleon; for Chester, derived from castra, Latin for camp, is the designation of military headquarters.

Camelot is thought to be Winchester. Shalott is Guildford. Hamo’s Port is Southampton.

Carlisle is the city still retaining that name, near the Scottish border. But this name is also sometimes applied to other places, which were, like itself, military stations.

[See: The thirty-three British cities named by Nennius]

Ambassadors were then sent into several kingdoms, to invite to court the princes both of Gaul and of the adjacent islands. Accordingly there came Augusel, king of Albania, now Scotland, Cadwallo, king of Venedotia, now North Wales, Sater, king of Demetia, now South Wales; also the archbishops of the metropolitan sees, London and York, and Dubricius, bishop of Caerleon, the City of Legions. This prelate, who was primate of Britain, was so eminent for his piety that he could cure any sick person by his prayers. There were also the counts of the principal cities, and many other worthies of no less dignity.

From the adjacent islands came Guillamurius, king of Ireland, Gunfasius, king of the Orkneys, Malvasius, king of Iceland, Lot, king of Norway, Bedver the butler, Duke of Normandy, Kay the sewer, Duke of Andegavia; also the twelve peers of Gaul, and Hoel, Duke of the Armorican Britons, with his nobility, who came with such a train of mules, horses, and rich furniture, as is difficult to describe. Besides these, there remained no prince of any consideration on this side of Spain who came not upon this invitation, and no wonder, when Arthur’s munificence, which was celebrated over the whole world, made him beloved by all people.

When all were assembled, upon the day of the solemnity, the archbishops were conducted to the palace in order to place the crown upon the king’s head. Then Dubricius, inasmuch as the court was held in his diocese, made himself ready to celebrate the office. As soon as the king was invested with his royal habiliments, he was conducted in great pomp to the metropolitan church, having four kings, viz., of Albania, Cornwall, Demetia, and Venedotia, bearing four golden swords before him. On another part was the queen, dressed out in her richest ornaments, conducted by the archbishops and bishops to the Church of Virgins; the four queens, also, of the kings last mentioned, bearing before her four white doves, according to ancient custom. When the whole procession was ended, so transporting was the harmony of the musical instruments and voices, whereof there was a vast variety in both churches, that the knights who attended were in doubt which to prefer, and therefore crowded from one to the other by turns, and were far from being tired of the solemnity, though the whole day had been spent in it. At last, when divine service was over at both churches, the king and queen put off their crowns, and, putting on their lighter ornaments, went to the banquet. When they had all taken their seats according to precedence, Kay the sewer, in rich robes of ermine, with a thousand young noblemen all in like manner clothed in rich attire, served up the dishes. From another part Bedver the butler was followed by the same number of attendants, who waited with all kinds of cups and drinking–vessels. And there was food and drink in abundance, and everything was of the best kind, and served in the best manner. For at that time Britain had arrived at such a pitch of grandeur that in riches, luxury, and politeness it far surpassed all other kingdoms.

As soon as the banquets were over they went into the fields without the city, to divert themselves with various sports, such as shooting with bows and arrows, tossing the pike, casting of heavy stones and rocks, playing at dice, and the like, and all these inoffensively, and without quarrelling. In this manner were three days spent, and after that they separated, and the kings and noblemen departed to their several homes.

After this Arthur reigned five years in peace. Then came ambassadors from Lucius Tiberius, Procurator under Leo, Emperor of Rome, demanding tribute. But Arthur refused to pay tribute, and prepared for war. As soon as the necessary dispositions were made, he committed the government of his kingdom to his nephew Modred and to Queen Guenever, and marched with his army to Hamo’s Port, where the wind stood fair for him. The army crossed over in safety, and landed at the mouth of the river Barba. And there they pitched their tents to wait the arrival of the kings of the islands.

As soon as all the forces were arrived, Arthur marched forward to Augustodunum, and encamped on the banks of the river Alba. Here repeated battles were fought, in all which the Britons, under their valiant leaders, Hoel, Duke of Armorica, and Gawain, nephew to Arthur, had the advantage. At length Lucius Tiberius determined to retreat, and wait for the Emperor Leo to join him with fresh troops. But Arthur, anticipating this event, took possession of a certain valley, and closed up the way of retreat to Lucius, compelling him to fight a decisive battle, in which Arthur lost some of the bravest of his knights and most faithful followers. But on the other hand Lucius Tiberius was slain, and his army totally defeated. The fugitives dispersed over the country, some to the by–ways and woods, some to the cities and towns, and all other places where they could hope for safety.

Arthur stayed in those parts till the next winter was over, and employed his time in restoring order and settling the government. He then returned into England, and celebrated his victories with great splendor.

Then the king established all his knights, and to them that were not rich he gave lands, and charged them all never to do outrage nor murder, and always to flee treason; also, by no means to be cruel, but to give mercy unto him that asked mercy, upon pain of forfeiture of their worship and lordship; and always to do ladies, damosels, and gentlewomen service, upon pain of death. Also that no man take battle in a wrongful quarrel, for no law, nor for any world’s goods. Unto this were all the knights sworn of the Table Round, both old and young. And at every year were they sworn at the high feast of Pentecost.

KING ARTHUR SLAYS THE GIANT OF ST. MICHAEL’S MOUNT

[See: The Giants Who Built The Mount]

While the army was encamped in Brittany, awaiting the arrival of the kings, there came a countryman to Arthur, and told him that a giant, whose cave was in a neighboring mountain, called St. Michael’s Mount, had for a long time been accustomed to carry off the children of the peasants, to devour them.

“And now he hath taken the Duchess of Brittany, as she rode with her attendants, and hath carried her away in spite of all they could do.”

“Now, fellow,” said King Arthur, “canst thou bring me there where this giant haunteth?”

“Yea, sure,” said the good man; “lo, yonder where thou seest two great fires, there shalt thou find him, and more treasure than I suppose is in all France beside.”

Then the king called to him Sir Bedver and Sir Kay, and commanded them to make ready horse and harness for himself and them; for after evening he would ride on pilgrimage to St. Michael’s Mount.

So they three departed, and rode forth till they came to the foot of the mount. And there the king commanded them to tarry, for he would himself go up into that mount. So he ascended the hill till he came to a great fire, and there he found an aged woman sitting by a new–made grave, making great sorrow. Then King Arthur saluted her, and demanded of her wherefore she made such lamentation; to whom she answered:

“Sir Knight, speak low, for yonder is a devil, and if he hear thee speak he will come and destroy thee. For ye cannot make resistance to him, he is so fierce and so strong. He hath murdered the Duchess, which here lieth, who was the fairest of all the world, wife to Sir Hoel, Duke of Brittany.”

“Dame,” said the king, “I come from the noble conqueror, King Arthur, to treat with that tyrant.” “Fie on such treaties,” said she; “he setteth not by the king, nor by no man else.”

“Well,” said Arthur, “I will accomplish my message for all your fearful words.” So he went forth by the crest of the hill, and saw where the giant sat at supper, gnawing on the limb of a man, and baking his broad limbs at the fire, and three fair damsels lying bound, whose lot it was to be devoured in their turn. When King Arthur beheld that he had great compassion on them, so that his heart bled for sorrow.

Then he hailed the giant, saying,

“He that all the world ruleth give thee short life and shameful death. Why hast thou murdered this Duchess? Therefore come forth, thou caitiff, for this day thou shalt die by my hand.”

Then the giant started up, and took a great club, and smote at the king, and smote off his coronal; and then the king struck him in the belly with his sword, and made a fearful wound. Then the giant threw away his club, and caught the king in his arms, so that he crushed his ribs. Then the three maidens kneeled down and prayed for help and comfort for Arthur. And Arthur weltered and wrenched, so that he was one while under, and another time above.

And so weltering and wallowing they rolled down the hill, and ever as they weltered Arthur smote him with his dagger; and it fortuned they came to the place where the two knights were. And when they saw the king fast in the giant’s arms they came and loosed him. Then the king commanded Sir Kay to smite off the giant’s head, and to set it on the truncheon of a spear, and fix it on the barbican, that all the people might see and behold it. This was done, and anon it was known through all the country, wherefor the people came and thanked the king. And he said,

“Give your thanks to God; and take ye the giant’s spoil and divide it among you.” And King Arthur caused a church to be builded on that hill, in honor of St. Michael.

Lancelot, whom the Lady of the Lake stole from his mother

From from Tennyson's Idylls of the King: Vivien, Elaine, Enid, Guinevere

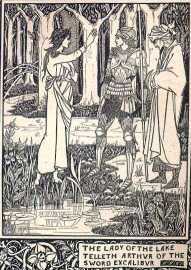

KING ARTHUR GETS A SWORD FROM THE LADY OF THE LAKE.

One day King Arthur rode forth, and on a sudden he was ware of three churls chasing Merlin to have slain him. And the king rode unto them and bade them,

“Flee, churls!”

Then were they afraid when they saw a knight, and fled.

“O Merlin,” said Arthur, “here hadst thou been slain, for all thy crafts, had I not been by.”

“Nay,” said Merlin, “not so, for I could save myself if I would; but thou art more near thy death than I am.”

So, as they went thus walking, King Arthur perceived where sat a knight on horseback, as if to guard the pass.

“Sir knight,” said Arthur, “for what cause abidest thou here?”

Then the knight said, “There may no knight ride this way unless he joust with me, for such is the custom of the pass.”

“I will amend that custom,” said the king.

Then they ran together, and they met so hard that their spears were shivered. Then they drew their swords and fought a strong battle, with many great strokes. But at length the sword of the knight smote King Arthur’s sword in two pieces.

Then said the knight unto Arthur, “Thou art in my power, whether to save thee or slay thee, and unless thou yield thee as overcome and recreant thou shalt die.”

“As for death,” said King Arthur, “welcome be it when it cometh; but to yield me unto thee as recreant I will not.”

Then he leapt upon the knight, and took him by the middle and threw him down; but the knight was a passing strong man, and anon he brought Arthur under him, and would have razed off his helm to slay him.

Then said Merlin, “Knight, hold thy hand, for this knight is a man of more worship than thou art aware of.”

“Why, who is he?” said the knight.

“It is King Arthur.”

Then would he have slain him for dread of his wrath, and lifted up his sword to slay him; and therewith Merlin cast an enchantment on the knight, so that he fell to the earth in a great sleep. Then Merlin took up King Arthur and set him on his horse.

“Alas!” said Arthur, “what hast thou done, Merlin? hast thou slain this good knight by thy crafts?” “Care ye not,” said Merlin; “he is wholer than ye be. He is only asleep, and will wake in three hours.”

Right so the king and he departed, and went unto an hermit that was a good man and a great leech. So the hermit searched all his wounds and gave him good salves; so the king was there three days, and then were his wounds well amended that he might ride and go, and so departed.

And as they rode Arthur said, “I have no sword.”

“No force,” said Merlin; “hereby is a sword that shall be yours.”

So they rode till they came to a lake, the which was a fair water and broad, and in the midst of the lake Arthur was ware of an arm clothed in white samite, that held a fair sword in that hand.

“So,” said Merlin, “yonder is that sword that I spake of.”

With that they saw a damsel going upon the lake.

“What damsel is that?” said Arthur.

“That is the Lady of the Lake,” said Merlin; “and within that lake is a rock, and therein is as fair a place as any on earth, and richly beseen, and this damsel will come to you anon, and then speak ye fair to her and she will give thee that sword.”

Anon withal came the damsel unto Arthur and saluted him, and he her again.

“Damsel,” said Arthur, “what sword is that that yonder the arm holdeth above the waves? I would it were mine, for I have no sword.”

“Sir Arthur king,” said the damsel, “that sword is mine, and if ye will give me a gift when I ask it you ye shall have it.”

“By my faith,” said Arthur, “I will give ye what gift ye shall ask.”

“Well,” said the damsel, “go you into yonder barge and row yourself to the sword, and take it and the scabbard with you, and I will ask my gift when I see my time.”

So Arthur and Merlin alighted, and tied their horses to two trees, and so they went into the ship, and when they came to the sword that the hand held, Arthur took it by the handles, and took it with him. And the arm and the hand went under the water.

[See: The Lady of the Lake by Sir Walter Scott]

Then they returned unto the land and rode forth. And Sir Arthur looked on the sword and liked it right well.

So they rode unto Caerleon, whereof his knights were passing glad. And when they heard of his adventures they marvelled that he jeopard his person so alone. But all men of worship said it was a fine thing to be under such a chieftain as would put his person in adventure as other poor knights did.