|

|

Armenian Mythology by Mardiros H. Ananikiam

CHAPTER III.

IRANIAN DEITIES

I. ARAMAZD

WHOEVER was the chief deity of the Armenians when they conquered Urartu, in later times that important position was occupied by Aramazd. Aramazd is an Armenian corruption of the Auramazda of the old Persian inscriptions. His once widely spread cult is one of our strongest proofs that at least a crude and imperfect form of Zoroastrianism existed in Armenia. Yet this Armenian deity is by no means an exact duplicate of his Persian namesake. He possesses some attributes that remind us of an older sky-god.

Unlike the Ahura-Mazda of Zoroaster, he was supreme, without being exclusive. There were other gods beside him, come from everywhere and anywhere, of whom he was the father. 1 Anahit, Nane and Mihr were regarded as his children in a peculiar sense. 2 Although some fathers of the Greek Church in the fourth century were willing to consider Armenian paganism as a remarkable approach to Christian monotheism, it must be confessed that this was rather glory reflected from Zoroastrianism, and that the supremacy of Aramazd seems never to have risen in Armenia to a monotheism that could degrade other gods and goddesses into mere angels (Ameshas and Yazatas). Aramazd is represented as the creator of heaven and earth by Agathangelos in the same manner as by Xerxes who says in one of his inscriptions: "Auramazda is a great god, greater than all gods, who has created this heaven and this earth." The Armenian Aramazd was called "great" 3 and he must have been supreme in wisdom (Armimastun, a cognate of mazdao) but he was most often char acterised as art, "manly," "brave," which is a good Armenian reminiscence of " Arya." 4

He seems to have been of a benign and peaceloving dis position, like his people, for whom wisdom usually conveys the idea of an inoffensive goodness. As far as we know he never figures as a warlike god, nor is his antagonism against the principle of evil as marked as that of the Avestic Ahura- Mazda. Nevertheless he no doubt stood and fought for the right (Armen. ardar "righteous," Iran., arda, Sansk. rita). Aramazd was above all the giver of prosperity and more especially of "abundance and fatness" in the land. Herein his ancient character of a sky-god comes into prominence. Amenaber, "bringer of all (good) things," was a beloved title of his. 5 He made the fields fertile and the gardens and the vineyards fruitful, no doubt through rain. The idea of an Earth goddess had become dim in the Armenian mind. But it is extremely possible that in this connection, something like the Thracian or Phrygian belief in Dionysos lingered among the people in connection with Aramazd, for, besides his avowed interest in the fertility of the country, his name was some times used to translate that of the Greek Dionysos. 6 Yet even the Persian Ahura-mazda had something to do with the plants (Ys. xliv. 4), and as Prof. Jackson says, he was a "generous" spirit.

It was in virtue of his being the source of all abundance that Aramazd presided at the Navasard (New Year's) festivals. These, according to the later (eleventh century) calendar, came towards the end of the summer and, beginning with the eleventh of August (Julian calendar), lasted six days, but originally the Armenian Navasard was, like its Persian prototype, celebrated in the early spring. 7 In spite of the fact that al-Biruni, according to the later Persian (Semitic?) view, makes this a festival commemorating the creation of the world, one may be reasonably sure that both in Armenia and in Persia, it was an agricultural celebration connected with commemo ration of the dead (see also chapter on Shahapet) and aiming at the increase of the rain and the harvests. In fact al-Biruni 8 informs us that in Navasard the Persians sowed "around a plate seven kinds of grain in seven columns and from their growth they drew conclusions regarding the corn of that year." 9 Also they poured water upon themselves and others, a custom which still prevails among Armenians at the spring sowing and at the festival of the Transfiguration in June. 10 This was originally an act of sympathetic magic to insure rain. Navasard's connection with Fravarti (Armen. Hrotik), the month consecrated to the ancestral souls in Persia and perhaps also in Armenia, is very significant, for these souls are in the old Aryan religion specially interested in the fertility of the land. The later (Christian) Navasard in August found the second crop of wheat on the threshing floor or safely garnered, the trees laden with mellowing fruit and the vintage in prog ress. 11 In many localities the Navasard took the character of a fete champetre celebrated near the sanctuaries, to which the country people flocked with their sacrifices and gifts, their rude music and rustic dances. But it was also observed in the towns and great cities where the more famous temples of Aramazd attracted great throngs of pilgrims. A special men tion of this festival is made by Moses (II, 66) in connection with Bagavan, the town of the gods. Gregory Magistros (eleventh century) says that King Artaxias (190 B.C.) on his death-bed, longing for the smoke streaming upward from the chimneys and floating over the villages and towns on the New Year's morning, sighed:

" O ! would that I might see the smoke of the

chimneys,

And the morning of the New Year's day,

The running of the oxen and the coursing of the deer!

(Then) we blew the horn and beat the drum as it beseemeth

Kings."

This fragment recalls the broken sentence with which al-Biruni's chapter on the Nauroz (Navasard) begins: "And he divided the cup among his companions and said, O that we had Nauroz every day! " 12

On these joyful days, Aramazd, the supremely generous and hospitable lord of Armenia, became more generous and hospitable. 13 No doubt the flesh of sacrifices offered to him was freely distributed among the poor, and the wayworn traveller always found a ready welcome at the table of the rejoicing pilgrims. The temples themselves must have been amply provided with rooms for the entertainment of strangers. It was really Aramazd-Dionysos that entertained them with his gifts of corn and wine.

Through the introduction of the Julian calendar the Armenians lost their Navasard celebrations. But they still preserve the memory of them, by consuming and distributing large quantities of dry fruit on the first of January, just as the Persians celebrated Nauroz, by distributing sugar. 14

No information has reached us about the birth or parentage of the Armenian Aramazd. His name appears sometimes as Ormizd in its adjectival form. But we do not hear that he was in any way connected with the later Magian speculation about Auramazda, which (perhaps under Hellenistic influences) made him a son of the limitless time (Zervana Akarana) and a twin brother of Ahriman. Moreover, Aramazd was a bachelor god. No jealous Hera stood at his side as his wedded wife, to vex him with endless persecutions. Not even Spenta-Armaiti (the genius of the earth), or archangels, and angels, some of whom figure both as daughters and consorts of Ahura-mazda in the extant Avesta (Ys. 454 etc.), appear in such an intimate connection with this Armenian chief deity. Once only in a martyrological writing of the middle ages Anahit is called his wife. 15 Yet this view finds no support in ancient authorities, though it is perfectly possible on a priori grounds.

Our uncertainty in this matter leaves us no alternative but to speculate vaguely as to how Aramazd brought about the existence of gods who are affiliated to him. Did he beget or create them? Here the chain of the myth is broken or left unfinished.

Aramazd must have had many sanctuaries in the country, for Armenian paganism was not the templeless religion which Magian Zoroastrianism attempted to become. The most highly honored of these was in Ani, a fortified and sacred city (perhaps the capital of the early Armenians) in the district of Daranali, near the present Erzinjan. It contained the tombs and mausolea of the Armenian kings, 16 who, as Gelzer suggests, slept under the peaceful shadow of the deity. Here stood in later times a Greek statue of Zeus, brought from the West with other famous images. 17 It was served by a large number of priests, some of whom were of royal descent. 18 This sanctuary and famous statue were destroyed by Gregory the Illuminator during his campaign against the pagan temples.

Another temple or altar of Aramazd was found in Bagavan (town of the gods) in the district of Bagrevand, 19 and still another on Mount Palat or Pashat along with the temple of AstXik. Moses of Khoren incidentally remarks 20 that there are four kinds of Aramazd, one of which is Kund ("bald ") 21 Aramazd. These could not have been four distinct deities, but rather four local conceptions of the same deity, repre sented by characteristic statues. 22

II. ANAHIT

After Aramazd, Anahit was the most important deity of Armenia. In the pantheon she stood immediately next to the father of the gods, but in the heart of the people she was supreme. She was " the glory," " the great queen or lady," " the one born of gold," " the golden-mother."

Anahit is the Ardvi Sura Anahita of the Avesta, whose name, if at all Iranian, would mean "moist, mighty, undefiled," a puzzling but not altogether unbefitting appellation for the yazata of the earth-born springs and rivers. But there is a marked and well-justified tendency to consider the Persian Anahita herself an importation from Babylonia. She is thought to be Ishtar under the name of Anatu or the Elamite " Nahunta." If so, then whatever her popular character may have been, she could not find a place in the Avesta without be ing divested of her objectionable traits or predilections. And this is really what happened. But even in the Avestic portraiture of her it is easy to distinguish the original. This Zoroastrian golden goddess of the springs and rivers with the high, pomegranate-like breasts had a special relation to the fecundity of the human race. She was interested in child-birth and nurture, like Ishtar, under whose protection children were placed with incantation and solemn rites. Persian maids prayed to her for brave and robust husbands. Wherever she went with the Persian armies and culture in Western Asia, Armenia, Pontus, Cappadocia, Phrygia, etc., her sovereignty over springs and rivers was disregarded and she was at once identified with some goddess of love and motherhood, usually with Ma or the Mater Magna. It would, therefore, be very reasonable to sup pose that there was a popular Anahita in Persia itself, who was nothing less than Ishtar as we know her. This is further confirmed by the fact that to this day the planet Venus is called Nahid by the Persians. 23

The Armenian Anahit is also Asianic in character. She does not seem to be stepping out of the pages of the Avesta as a pure and idealized figure, but rather she came there from the heart of the common people of Persia, or Parthia, and must have found some native goddess whose attributes and ancient sanctuaries she assimilated. She has hardly anything to do with springs and rivers. She is simply a woman, the fair daughter of Aramazd, a sister of the Persian Mihr and of the cosmopolitan Nane. As in the Anahit Yashts of the A vesta, so also in Armenia, " golden " is her fairest epithet. She was often called " born in gold " or " the golden mother" probably because usually her statue was of solid gold.

In the light of what has just been said we are not surprised to find that this goddess exhibited two distinct types of woman hood in Armenia, according to our extant sources. Most of the early Christian writers, specially Agathangelos, who would have eagerly seized upon anything derogatory to her good name, report nothing about her depraved tastes or unchaste rites.

If not as a bit of subtle sarcasm, then at least as an echo of the old pagan language, King Tiridates is made to call her "the mother of all sobriety," i.e. orderliness, as over against a lewd and ribald mode of life. 24 The whole expression may also be taken as meaning "the sober, chaste mother." No sugges tion of impure rites is to be found in Agathangelos or Moses in connection with her cultus.

On the other hand no less an authority than the geographer Strabo (63 B.C.-25A.D.) reports that the great sanctuary of Anahit at Erez (or Eriza), in Akilisene (a district called also Anahitian 25 owing to the widely spread fame of this temple) was the centre of an obscene form of worship. Here there were hierodules of both sexes, and what is more, here daugh ters of the noble families gave themselves up to prostitu tion for a considerable time, before they were married. Nor was this an obstacle to their being afterwards sought in marriage. 26

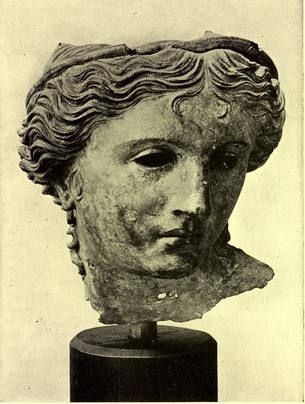

PLATE III: Bronze Head of Anahit, a Greek work (probably Aphrodite) found at Satala, worshipped by the Armenians, now in the British Museum.

Strabo is not alone in representing Anahit in this particularly sad light. She was identified with the Ephesian Artemis by the Armenians themselves. Faustus of Byzantium, writing in the fifth century, says of the imperfectly Christianized Armenians of the preceding century, that they continued "in secret the worship of the old deities in the form of fornication." 27 The reference is most probably to the rites of the more popu lar Anahit rather than her southern rival, AstXik, whom the learned identified with Aphrodite, and about whose worship no unchastity is mentioned. Mediaeval authors of Armenia also assert similar things about Anahit. Vanakan Vardapet says, " Astarte is the shame of the Sidonians, which the Chal deans (Syrians or Mesopotamians) called Kaukabhta, the Greeks, Aphrodite, and the Armenians, Anahit." 28

In a letter to Sahag Ardsruni, ascribed to Moses of Khoren, 29 we read that in the district of Antzevatz there was a famous Stone of the Blacksmiths. Here stood a statue of Anahit and here the blacksmiths (no doubt invisible ones) made a dreadful din with their hammers and anvils. The devils (i.e. idols) dispensed out of a melting pot bundles of false medicine which served the fulfilling of evil desires, "like the bundle of St. Cyprian intended for the destruction of the Virgin Justina." 30 This place was changed later into a sanctuary of the Holy Virgin and a convent for nuns, called Hogeatz vank.

There can be no doubt, therefore, that the Armenian Anahit admitted of the orgiastic worship that in the ancient orient characterized the gods and especially the goddesses of fertility. No doubt these obscene practices were supposed to secure her favor. On the other hand it is quite possible that she played in married life the well-known role of a mother of sobriety like Hera or rather Ishtar, 31 the veiled bride and protector of wedlock, jealously watching over the love and faith plighted between husband and wife, and blessing their union. We may therefore interpret in this sense the above mentioned description of this goddess, which Agathangelos 32 puts in the mouth of King Tiridates: " The great lady (or queen) Anahit, who is the glory and life-giver of our nation, whom all kings honour, especially the King of the Greeks (sic!), who is the mother of all sobriety, and a benefactress (through many favours, but especially through the granting of children) of all mankind; through whom Armenia lives and maintains her life." Although clear-cut distinctions and schematic arrangements are not safe in such instances, one may say in general that Aramazd once created nature and man, but he now (speaking from the standpoint of a speculative Armenian pagan of the first century) sustains life by giving in abundance the corn and the wine. Anahit, who also may have some interest in the growth of vegetation, gives more especially young ones to animals and children to man, whom she maternally tends in their early age as well as in their strong manhood. Aramazd is the god of the fertility of the earth, Anahit the goddess of the fecundity of the nation.

However, as she was deeply human, the birth and care of children could not be her sole concern. As a merciful and mighty mother she was sought in cases of severe illness and perhaps in other kinds of distress. Agathangelos mentions the care with which she tends the people. In Moses 33 we find that King Artaxias, in his last sickness, sent a nobleman to Erez to propitiate the tender-hearted goddess. But unlike Ishtar and the Persian Anahita, the Armenian Anahit shows no war-like propensities, nor is her name associated with death.

Like Aramazd, she had many temples in Armenia, but the most noted ones were those of Erez, Artaxata, Ashtishat, and Armavir. 34 There was also in Sophene a mountain called the Throne of Anahit, 35 and a statue of Anahit at the stone of the Blacksmiths. The temple at Erez was undoubtedly the rich est sanctuary in the country and a favorite centre of pilgrim age. It was taken and razed to the ground by Gregory the Illuminator. 36 It was for the safety of its treasures that the natives feared when Lucullus entered the Anahitian province. 37

Anahit had two annual festivals, one of which was held, according to Alishan, on the 15th of Navasard, very soon after the New Year's celebration. Also the nineteenth day of every month was consecrated to her. A regular pilgrimage to her temple required the sacrifice of a heifer, a visit to the river Lykos near-by, and a feast, after which the statue of the god dess was crowned with wreaths. 36 Lucullus saw herds of heifers of the goddess, 39 with her mark, which was a torch, wander up and down grazing on the meadows near the Euphrates, without being disturbed by anyone. The Anahit of the countries west of Armenia bore a crescent on her head.

We have already seen that the statues representing Anahit in the main sanctuaries, namely in Erez, Ashtishat, and probably also in Artaxata, were solid gold. According to Pliny 40 who describes the one at Erez, this was an unprecedented thing in antiquity. Not under Lucullus, but under Antonius did the Roman soldiers plunder this famous statue. A Bononian veteran who was once entertaining Augustus in a sumptuous style, declared that the Emperor was dining off the leg of the goddess and that he had been the first assailant of the famous statue, a sacrilege which he had committed with im punity in spite of the rumours to the contrary. 41 This statue may have been identical with the (Ephesian) Artemis which, according to Moses, 42 was brought to Erez from the west.

III. TIUR (TIR)

Outside of Artaxata, the ancient capital of Armenia (on the Araxes), and close upon the road to Valarshapat (the winter capital), was the best known temple of Tiur. The place was called Erazamuyn , which probably means "interpreter of dreams." 43Tiur had also another temple in the sacred city of Armavir. 44

He was no less a personage than the scribe of Aramazd, which may mean that in the lofty abode of the gods, he kept record of the good and evil deeds of men for a future day of reckoning, or what is more probable on comparative grounds, he had charge of writing down the decrees (hraman, Pers. firman) that were issued by Aramazd concerning the events of each human life. 45 These decrees were no doubt recorded not only on heavenly tablets but also on the forehead of every child of man that was born. The latter were commonly called the " writ on the forehead " 46 which, according to present folk lore, human eyes can descry but no one is able to decipher.

Besides these general and pre-natal decrees, the Armenians seem to have believed in an annual rendering of decrees, resembling the assembly of the Babylonian gods on the world-mountain during the Zagmuk (New Year) festival. They located this event on a spring night. As a witness of this we have only a universally observed practice.

In Christian Armenia that night came to be associated with Ascension Day. The people are surely reiterating an ancient tradition when they tell us that at an unknown and mystic hour of the night which precedes Ascension silence envelops all nature. Heaven comes nearer. All the springs and streams cease to flow. Then the flowers and shrubs, the hills and stones, begin to salute and address one another, and each one declares its specific virtue. The King Serpent who lives in his own tail learns that night the language of the flowers. If anyone is aware of that hour, he can change everything into gold by dipping it into water and expressing his wish in the name of God. Some report also that the springs and rivers flow with gold, which can be secured only at the right moment. On Ascension Day the people try to find out what kind of luck is awaiting them during the year, by means of books that tell fortune, or objects deposited on the previous day in a basin of water along with herbs and flowers. A veil covers these things which have been exposed to the gaze of the stars during the mystic night, and a young virgin draws them out one by one while verses divining the future are being recited." 47

Whether Tiur originally concerned himself with all these things or not, he was the scribe of Aramazd. Being learned and skilful, he patronized and imparted both learning and skill. His temple, called the archive 48 of the scribe of Ara mazd, was also a temple of learning and skill, i.e. not only a special sanctuary where one might pray for these things and make vows, but also a school where they were to be taught. Whatever else this vaunted learning and skill included, it must have had a special reference to the art of divination. It was a kind of Delphic oracle. This is indirectly attested by the fact that Tiur, who had nothing to do with light, was identified with Apollo in Hellenic times, 49 as well as by the great fame for interpretation of dreams which Tiur's temple enjoyed. Here it was that the people and the grandees of the nation came to seek guidance in their undertakings and to submit their dreams for interpretation. The interpretation of dreams had long become a systematic science, which was handed down by a clan of priests or soothsayers to their pupils. Tiur must have also been the patron of such arts as writing and eloquence, for on the margin of some old Armenian MSS. of the book of Acts (chap, xiv, v. 12), the name of Her mes, for whom Paul was once mistaken because of his eloquence, was explained as "the god Tiur."

Besides all these it is more than probable that Tiur was the god who conducted the souls of the dead into the nether world. The very common Armenian imprecation, " May the writer carry him! " 50 or "The writer for him! " as well as Tiur's close resemblance to the Babylonian Nabu in many other respects, goes far to confirm this view.

In spite of his being identified with Apollo and Hermes, Tiur stands closer to the Babylonian Nabu 51 than to either of these Greek deities. In fact, Hermes himself must have developed on the pattern of Nabu. The latter was a god of learning and of wisdom, and taught the art of writing. He knew and so he could impart the meaning of oracles and incantations. He inspired (and probably interpreted) dreams. In Babylonia Nabu was identified with the planet Mercury.

But the name of Tiur is a proof that the Babylonian Nabu did not come directly from the South. By what devious way did he then penetrate Armenia?

The answer is simple. In spite of the puzzling silence of the Avesta on this point, Iran knew a god by the name of Tir. One of the Persian months, as the old Cappadocian and Armenian calendars attest, was consecrated to this deity (perhaps also the thirteenth day of each month). We find among the Iranians as well as among the Armenians, a host of theophorous names composed with "Tir" such as Tiribazes, Tiridates, Tiran, Tirikes, Tirotz, Tirith, etc., bearing unimpeachable wit ness to the god's popularity. Tiro-naKathwa is found even in the Avesta 52 as the name of a holy man. It is from Iran that Tir migrated in the wake of the Persian armies; and civilization to Armenia, Cappadocia, and Scythia, where we find also Tir's name as Teiro on Indo-Scythian coins of the first century of our era. 53

We have very good reasons to maintain that the description of the Armenian Tiur fits also the Iranian Tir, and that they both were identical with Nabu. As Nabu in Babylonia, so also Tir in Iran was the genius presiding over the planet Mercury and bore the title of Dabir, " writer." 55

But a more direct testimony can be cited bearing on the

original identity of the Persian Tir with Nabu. The

Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar was greatly devoted to Nabu,

his patron god. He built at the mouth of the Euphrates a city

which he dedicated to him and called by a name containing the

deity's name, as a component part. This name was rendered in

Greek by Berossus (or Abydenus?) as ![]() , "given to Mercury." The

latter form, says Rawlinson, occurs as early as the time of

Alexander. 55 The arrow-like

writing-wedge was the commonest symbol of Nabu, and could easily

give rise to the Persian designation. 56 That the arrow seems to have been the

underlying idea of the Persian conception of Nabu is better

attested by the fact that both Herodotus and Armenian history

know the older form of Tiran, Tigranes, as a common name.

Tigranes is, no doubt, derived from Tigris old Persian for

"arrow."

, "given to Mercury." The

latter form, says Rawlinson, occurs as early as the time of

Alexander. 55 The arrow-like

writing-wedge was the commonest symbol of Nabu, and could easily

give rise to the Persian designation. 56 That the arrow seems to have been the

underlying idea of the Persian conception of Nabu is better

attested by the fact that both Herodotus and Armenian history

know the older form of Tiran, Tigranes, as a common name.

Tigranes is, no doubt, derived from Tigris old Persian for

"arrow."

IV. MIHR (MITHRA)

Our knowledge of the Armenian Mihr is unfortunately very fragmentary. He was unquestionably Iranian. Although popular at one time, he seems to have lost some ground when we meet with him. His name Mihr (Parthian or Sassanian for Mithra) shows that he was a late comer. Nevertheless he was called the son of Aramazd, and was therefore a brother of Anahit and Nane. In the popular Zoroastrianism of Persia, especially in Sassanian times, we find that the sun (Mihr) and moon were children of Ormazd, the first from his own mother, or even from a human wife, and the moon, from his own sis ter. 57 Originally Mihr may have formed in Armenia a triad with Aramazd and Anahit like that of Artaxerxes Mnemon's inscriptions. If so he soon had to yield that place to the national god Vahagn.

The Armenian Mithra presents a puzzle. If he was a genius of light and air, a god of war and contracts, a creature of Aramazd equal in might to his creator, as we find him to be in the Avesta, no trace of such attributes is left. But for the Armenians he was the genius or god of fire, and that is why he was identified with Hephaistos in syncretistic times. 58 This strange development is perhaps further confirmed by the curious fact that until this day, the main fire festival of the Armenians comes in February, the month that once corre sponded to the Mehekan (dedicated to Mihr) of the Armenian calendar. But it must not be overlooked that all over the Indo-European world February was one of the months in which the New Fires were kindled.

The connection of Mihr with fire in Armenia may be ex plained as the result of an early identification with the native Vahagn, who, as we shall see, was a sun, lightning, and fire-god. This conjecture acquires more plausibility when we remember that Mihr did not make much headway in Armenia and that finally Vahagn occupied in the triad the place which, by right and tradition, belonged to Mihr.

Of Mithraic mysteries in Armenia we hear nothing. There were many theophorous names compounded with his name, such as Mihran, Mihrdat. The Armenian word " Mehyan" " temple," seems also to be derived from his name.

We know that at the Mithrakana festivals when it was the privilege of the Great King of Persia to become drunk (with haoma?), a thousand horses were sent to him by his Armenian vassal. We find in the region of Sassun (ancient Tarauntis) a legendary hero, called Meher, who gathers around himself a good many folk-tales and becomes involved even in eschatological legends. He still lives with his horse as a captive in a cave called Zympzymps which can be entered in the Ascension night. There he turns the wheel of fortune, and thence he will appear at the end of the world.

The most important temple dedicated to Mihr was in the village of Bagayarij (the town of the gods) in Derjan, Upper Armenia, where great treasures were kept. This sanctuary also was despoiled and destroyed by Gregory the Illuminator. It is reported that in that locality Mihr required human sacrifices, and about these Agathangelos also darkly hints. 59 This is, however, very difficult to explain, for in Armenia offerings of men appear only in connection with dragon (i.e. devil) worship. On the basis of the association of Mihr with eschatological events, we may conjecture that the Armenian Mihr had gradually developed two aspects, one being that which we have described above, and the other having some mysterious re lation to the under-world powers. 60

V. SPANTARAMET

The Amesha Spenta, Spenta Armaiti (holy genius of the earth) and the keeper of vineyards, was also known to the translators of the Armenian Bible who used her name in 2 Mace. vi. 7, to render the name of Dionysos.

However, it would seem that she did not hold a place in the Armenian pantheon, and was known only as a Persian goddess. We hear of no worship of Spantaramet among the Armenians and her name does not occur in any passage on Armenian religion. It is very strange, indeed, that the translators should have used the name of an Iranian goddess to render that of a Greek god. Yet the point of contact is clear. Among the Persians Spenta Armaiti was popularly known also as the keeper of vineyards, and Dionysos was the god of the vine. But, whether it is because of the evident dissimilarity of sex or because the Armenians were not sufficiently familiar with Spantaramet, the translators soon (2 Mace. xiv. 33 j 3 Mace. ii. 29) discard her name and use for Dionysos " Ormzdakan god," i.e. Aramazd, whose peculiar interest in vegetation we have already noticed. Spenta Armaiti was better known to the ancient religion of Armenia as Santaramet, the goddess of the under-world.

The worship of the earth is known to Eznik 61 as a magian and heathen practice, but he does not directly connect it with the Armenians, although there can be little doubt that they once had an earth-goddess, called Erkir (Perkunas) or Armat, in their pantheon.

NOTES

1. Agathangelos, p. 590.

2. Seeing that Anahit was in later times identified with Artemis and Nane, with Athene and Mihr and with Hephaistos, one may well ask whether this fathering of Aramazd upon them was not a bit of Hellenizing. Yet the Avesta does not leave us without a parallel in this matter.

3. Agathangelos, pp. 52, 6 1.

4. Ibid., pp. 52, 6 1, 1 06.

5. Ibid., p. 623.

6. It is noteworthy that his Christian successor is a hurler of the lightning.

7. See artts. " Calendar (Armenian) " and " Calendar (Persian) " in ERE iii. 70 f., 128 f.

8. Al-Biruni, Chron., pp. 202203.

9. This is an important instance of the Adonis gardens in the East, overlooked by Frazer. Readers of his Adonis, Attis, and Osiris know how widely the custom had spread in the West.

10. See Chap. 8.

11. Gregory the Illuminator substituted the festival of St. John Baptist for that of the Navasard, but as that festival did not attain more than a local popularity (in Tarauntis) the later Fathers seem to have united it with the great festival of the Assumption of the Virgin, at which the blessing of the grapes takes place. These Christian associations gradually cost the old festival many of its original traits.

12. Al-Blruni, Chron. y p. 199.

13. Moses, ii. 66; Agathangelos, p. 623. Gelzer and others have made of his title of Vanatur, " hospitable," a separate deity. However corrupt the text of Agathangelos may be, it certainly does not justify this inference. Further, Vanatur is used in the Book of Maccabees to translate Zeus Xenios. For a fuller discussion of this subject see art. " Armenia (Zoroastrian) " in ERE i. 795.

14. Al-Blruni, Chron.,p. 20O.

15. Quoted by Alishan, p. 260. It is perhaps on this basis that Gelzer gives her the title of " mother of gods." This title finds no support in ancient records.

1 6. Agathangelos, p. 590. This cannot be Zoroastrian.

17. Moses, ii. 12.

1 8. Ibid., ii. 53.

19. Agathangelos, p. 6 1 2.

20. Moses, i. 31.

21. Kund in Persian may mean "brave." But the word does not occur in Armenian in this sense.

22. The Iberians also had a chief deity called Azmaz (a corruption of Aramazd), whose statue, described as "the thunderer " or "a hurler of lightning," was set up outside of their capital, Mdskhit. A mighty river flowed between the temple and the city. As the statue was visible from all parts of the city, in the morning everyone stood on his house-roof to worship it. But those who wished to sacrifice, had to cross the river in order to do so at the temple. (Alishan,

P-SH-)

23. Whenever she may have come to Persia, her patronage over the rivers and springs need not be regarded as a purely Iranian addition to her attributes. The original Ishtar is a water goddess, and therefore a goddesss of vegetation, as well as a goddess of love and maternity. Water and vegetation underlie and symbolize all life whether animal or human. Cf. Mythology of all Races, Boston, 1917, vi. 278 f.

24. Agathangelos, p. 52.

25. Dio. Cass., 36, 48; Pliny, HN v. 83.

26. Strabo, xi. 532C. Cumont thinks that this was a modification of ancient exogamy (see art. " Anahita " in ERE i. 414, and his Les religions orientates dans le faganisme romain, Paris, 1907, p. 287). Yet it is difficult to see wherein this sacred prostitution differs from the usual worship paid to Ishtar and Ma. As Ramsay explains it in his art. " Phrygians " (ERE ix. 900 f.) this is an act which is supposed to have a magical influence on the fertility of the land and perhaps also on the fecundity of these young women. Cf . arts. " Ashtart " (ERE ii. H5f.) and " Hicrodouloi (Semitic and Egyptian) " (ERE vi. 672 f.).

27. Faustus, iii. 13.

28. Alishan, p. 263.

29. Moses, p. 294.

30. Justina was a Christian virgin of Antioch whom a certain magician called Cyprian tried to corrupt by magical arts, first in favor of a friend, then for himself. His utter failure led to his conversion, and both he and Justina were martyred together.

31. We have already seen (p. n) that Ishtar as Sharis had secured a place in the Urartian pantheon.

32. Agathangelos, pp. 51, 61.

33. Moses, ii. 60.

34. Ibid, ii. 12.

35. Faustus, v. 25.

36. Agathangelos, p. 591.

37. Cicero, De imferio Pompii, p. 23.

38. Agathangelos, p. 59; Weber, p. 31.

39. Farther west Anahit required bulls, and was called Taurobolos.

40. HN xxxiii. 4; see Gelzer, p. 46.

41. Pliny, loc. cit.

42. Moses, ii. 1 6.

43. Eraz, " dream," is identical with the Persian word raz, " secret," " occult," and perhaps also with the Slavic raj, " the other world," or " paradise." Muyn is now unintelligible and the AOIXTOS of the Greek is evidently a mere reproduction of the cryptic muyn.

44. Moses, ii. 12.

45. Tiur's name occurs also as Tre in the list of the Armenian months. In compound names and words it assumes the Persian form of Tin We find a " Ti " in the old exclamation " (By) Ti or Tir, forward! " and it may be also in such compound forms as Ti-air, Ti-mann, a " lord," and Ti-kin, " a Ti-woman," i.e., " lady," " queen." Ti-air may be compared with Tirair, a proper name of uncertain derivation. However, owing to the absence of the " r " m Ti, one may well connect it with the older Tiv, a cognate of Indo-European Dyaus, Zeus, Tiwaz, etc., or one may consider it as a dialectical variety of the Armenian di, " god."

3 84 ARMENIAN MYTHOLOGY

46. Eznik, pp. 150, 153, etc. Synonymous or parallel with this, we find also the word bakht y " fortuna."

47. Pshrank, p. 271. See for a fuller account Abeghian, p. 6 if.

48. Perhaps because, like the temple of Nabu in Borsippa, it contained a place symbolizing the heavenly archive in which the divine decrees were deposited.

49. Agathangelos.

50. " The Writer " was confused with the angel of death in Christian times. He is now called "the little brother of death." It is curious to note that the Teutonic Wotan, usually identified with Mercury, was also the conductor of souls to Hades.

51. Nabu, the city-god of Borsippa, once had precedence over Marduk himself in the Babylonian Pantheon. But when Marduk, the city god of Babylon, rose in importance with the political rise of his city, Nabu became the scribe of the gods and their messenger, as well as the patron of the priests. On the Babylonian New Year's Day (in the spring) he wrote on tablets, the destiny of men, when this was decided on the world mountain.

52. Farvardin Yasht, xxvii. 126.

53. Moulton, p. 435. Even the Arabs knew this deity under the name of c UTarid, which also means Mercury, and has the epithet of " writer."

54. There lies before us no witness to the fact that the Armenians ever called the planet Mercury, Tiur, but it is probable. The Persians themselves say that Mercury was called Tir y " arrow," on account of its swiftness.

55. See G. Rawlinson's Herodotus y app. Bk. i, under Nebo.

56. Jensen derives Tir from the Babylonian Dpir = Dipsar, " scribe." However, he overlooks the fact that the East has known and used the word Dpir in an uncorrupted form to this day. Tir may even be regarded as one element in the mysterious Hermes Tresmegisthos, which is usually translated as " Thrice greatest." It seems to be much more natural to say: Hermes, the greatest Tir. However, we have here against us the great army of classical scholars and a hoary tradition.

57. Eznik, pp. 122, 138; also EXishe, ii. 44. F. Cumont, in his Mysteries of Mithra y wrongly ascribes these myths to the Armenians themselves, whereas the Armenian authors are only reporting Zrvantian ideas.

58. Greek Agathangelos; Moses, ii. 1 8.

59. Agathangelos, p. 593. One of the gates of the city of Van is to this day called by Mihr's name (Meher).

60. These human sacrifices may also be explained by Mihr's probable relation to Vahagn. Vahagn is the fierce storm god, who, as in Vedic and Teutonic religions, had supplanted the god of the bright heaven. Vahagn may have once required human sacrifices in Armenia, as his Teutonic brother Wotan did.

61. Eznik, pp. 15, 1 6.