|

|

Armenian Mythology by Mardiros H. Ananikiam

CHAPTER X.

HEROES

THE loss of the ancient songs of Armenia is especially regrettable at this point, because they concerned themselves mostly with the purely national gods and heroes. The first native writers of Armenian history, having no access to the ancient Assyrian, Greek, and Latin authors, drew upon this native source for their material. Yet the old legends were modified or toned down in accordance with euhemeristic views and accommodated to Biblical stories and Greek chronicles, especially that of Eusebius of Caesarea. It is quite possible that the change had already begun in pagan times, when Iranian and Semitic gods made their conquest of Armenia.

I. HAYK

There can be little doubt that the epic songs mentioned Hayk first of all. Hayk was a handsome giant with finely proportioned limbs, curly hair, bright smiling eyes, and a strong arm, who was ready to strike down all ambition, divine or human, which raised its haughty head and dreamt of absolute dominion. The bow and the triangular arrow were his inseparable companions. Hayk was a true lover of independence. He it was, who, like Moses of old, led his people from the post-diluvian tyranny of Bel (Nimrod) in the plain of Shinar to the cold but free mountains of Armenia, where he subjugated the native population. 1 Bel at first plied him with messages of fair promise if he would return. But the hero met them with a proud and defiant answer. Soon after, as was expected, Cadmus, the grandson of Hayk, brought tidings of an invasion of Armenia by the innumerable forces of Bel. Hayk marched south with his small but brave army to meet the tyrant on the shores of the sea (of Van) "whose briny waters teem with tiny fish." 2 Here began the battle. Hayk arranged his warriors in a triangle on a plateau among mountains in the presence of the great multitude of invaders. The first shock was so terrible and costly in men that Bel, confused and frightened, began to withdraw. But Hayk's unerring triangular arrow, piercing his breast, issued forth from his back. The overthrow of their chief was a signal for the mighty Babylonian forces to disperse.

Hayk is the eponymous hero of the Armenians according to their national name, Hay, used among themselves. From the same name they have called their country Hayastan or the Kingdom (Ashkharh = Iran. Khshathra) of the Hays. Adjectives derived from Hayk describe both gigantic strength and great beauty. Gregory of Narek calls even the beauty of the Holy Virgin, Hayk-like! The word Hayk itself was often used in the sense of a " giant."

Some have tried to give an astronomical interpretation to this legend. Pointing out the fact that Hayk is also the Ar menian name for the constellation Orion, they have main tained that the triangular arrangement of Hayk's army re flects the triangle which the star Adaher in Orion forms with the two dogstars. However, any attempt to establish a parallelism between the Giant Orion and Hayk as we know him, is doomed to failure, for beyond a few minor or general points of resemblance, the two heroes have nothing in com mon. Hayk seems to have been also the older Armenian name of the Zodiacal sign Libra, and of the planet Mars, 3 while the cycle of Sirius was for the Armenians the cycle of Hayk.

The best explanation of Hayk's name and history seems to lie in the probable identity of Hayk (Hayik, "little Hay," just as Armenak means " little Armenius ") with the Phrygian sky-god Hyas. Both the Greeks and the Assyrians 4 know him as an independent Thraco-Phrygian deity. The Assyrians call him the god of Moschi. 5 In a period when everything Thracian and Phryg ian was being assimilated by Dionysos or was sinking into insignificance before his triumphant march through the Thraco-Phrygian world, Hyas, from a tribal deity, became an epithet of this god of vegetation and of wine. For us Hyas is no one else but the Vayu of the Vedas and the Avesta. So in the legend of Hayk we probably have the story of the battle between an Indo-European weather-god and the Mesopotamian Bel. It is very much more natural to derive a national name like Hay from a national deity's name, according to the well-known analogies of Assur and Khaldi, than to interpret it as pati, " chief." 6

II. ARMENAK

According to Moses of Chorene, Armenak is the name of the son of Hayk. He chose for his abode the mountain Aragads (now Alagez) and the adjacent country.

He is undoubtedly another eponymous hero of the Armenian race. Armenius, father of Er, mentioned by Plato in his Republic7 can be no other than this Armenak who, according to Moses of Chorene and the so-called Sebeos-fragments, is the great-grandfather of Ara (Er). The final syllable is a diminutive, just as is the "k" in Hayk. Popular legend, which occupied itself a good deal with Hayk, seems to have neglected Armenak almost completely. It is quite possible that Armenak is the same as the Teutonic Irmin and the Vedic Aryaman, therefore originally a title of the sky-god. The many exploits ascribed to Aram, the father of Ara, may indeed, belong by right to Armenak. 8

III. SHARA

Shara is said to be the son of Armais. As he was uncommonly voracious his father gave him the rich land of Shirak to prey upon. He was also far-famed for his numerous progeny. The old Armenian proverb used to say to gluttons: "If thou hast the throat (appetite) of Shara, we have not the granaries of Shirak." One may suspect that an ogre is hiding behind this ancient figure. At all events his name must have some affinity with the Arabic word Sharah, which means gluttony. 9

IV. ARAM

Aram, a son of Harma, seems to be a duplicate of Armenak, although many scholars have identified him with Arame, a later king of Urartu, and with Aram, an eponymous hero of the Aramaic region. The Armenian national tradition makes him a conqueror of Barsham "whom the Syrians deified on account of his exploits," of a certain Nychar Mades (Nychar the Median), and of Paiapis Chalia, a Titan who ruled from the Pontus Euxinus to the Ocean (Mediterranean). Through this last victory Aram became the ruler of Pontus and Cappadocia upon which he imposed the Armenian language.

In this somewhat meagre and confused tale we have prob ably an Armenian god Aram or Armenius in war against the Syrian god Ba al Shamin, some Median god or hero called Nychar, 10 and a western Titan called Paiapis Chaxia, who no doubt represents in a corrupt form the Urartian deity Khaldi with the Phrygian (?) title of Papaios. The legend about the Pontic war probably originated in the desire to explain how Armenians came to be found in Lesser Armenia, or it may be a distant and distorted echo of the Phrygo-Armenian struggles against the Hittite kingdoms of Asia Minor.

V. ARA, THE BEAUTIFUL

With Ara we are unmistakably on mythological ground. Unfortunately this interesting hero has, like Hayk and Aram, greatly suffered at the hands of our ancient Hellenizers. The present form of the myth, a quasi-classical version of the original, is as follows: When Ninus, King of Assyria, died or fled to Crete from his wicked and voluptuous queen Semiramis, the latter having heard of the manly beauty of Ara, proposed to marry him or to hold him for a while as her lover. But Ara scornfully rejected her advances for the sake of his beloved wife Nvard. Incensed by this unexpected rebuff, the impetuous Semiramis came against Ara with a large force, not so much to punish him for his obstinacy as to capture him alive. Ara's army was routed and he fell dead during the bloody encounter. At the end of the day, his lifeless body having been found among the slain, Semiramis removed it to an upper room of his palace hoping that her gods (the dog-spirits called Aralezes) would restore him to life by licking his wounds. Although, according to the rationalizing Moses of Chorene, Ara did not rise from the dead, the circumstances which he mentions leave no doubt that the original myth made him come back to life and continue his rule over the Armenians in peace. For, according to this author, 11 when Ara's body began to decay, Semiramis dressed up one of her lovers as Ara and pretended that the gods had fulfilled her wishes. She also erected a statue to the gods in thankfulness for this favor and pacified Armenian minds by persuading them that Ara was alive.

Another version of the Ara story is to be found at the end of Plato's Republic?12 where he tells us that a certain Pamphylian hero called Er, son of Armenius, " happening on a time to die in battle, when the dead were on the tenth day carried off, already corrupted, was taken up sound; and being carried home as he was about to be laid on the funeral pile, he revived, and being revived, he told what he saw of the other state." The long eschatological dissertation which follows is probably Thracian or Phrygian, as these peoples were especially noted for their speculations about the future life.

The Pamphylian Er's parentage, as well as the Armenian version of the same story, taken together, make it highly probable that we have here an Armenian (or Phrygian), rather than Pamphylian, 13 myth, although by some queer chance it may have reached Greece from a Pamphylian source. Semiramis may be a popular or learned addition to the myth. But it is quite reasonable to assume that the original story represented the battle as caused by a disappointed woman or goddess. An essential element, preserved by Plato, is the report about life beyond the grave. The Armenian version reminds us strongly of that part of the Gilgamesh epic in which Ishtar appears in the forest of Cedars guarded by Khumbaba to allure Gilgamesh, a hero or demi-god, with attributes of a sun-god, into the role of Tammuz. We know how Gilgamesh refused her advances. Eabani, the companion of Gilgamesh, seems to be a first (primaeval) man who was turning his rugged face towards civilization through the love of a woman. He takes part in the wanderings of Gilgamesh, and fights with him against Ishtar and the heavenly bull sent by Anu to avenge the insulted goddess. Apparently wounded in this struggle Eabani dies. Thereupon Gilgamesh wanders to the world of the dead in search of the plant of life. On his return he meets with Eabani who has come back from the region of the dead, to inform him of the condition of the departed, and of the care with which the dead must be buried in order to make life in Aralu (Hades) bearable.14

Possibly the original Ara story goes back to this Babylonian epic but fuses Gilgamesh and Eabani into one hero.

Sayce suggests that Ara may be the Eri of the Vannic in scriptions and the latter may have been a sun-god. 15

VI. TIGRANES, THE DRAGON-FIGHTER

This story also must be interpreted mythologically, although it is connected with two historical characters. It is a dragon legend which does not contain the slightest fraction of historical fact, but was manifestly adapted to the story of Astyages in the first book of Herodotus. For the sake of brevity we shall not analyse it in detail, as its chief elements will be brought out in the chapter on dragons. The rationalizing zeal of the later Armenian authors has evidently made use of the fact that Azdahak y " dragon," was also the name of a famous Median king in the times of Cyrus the Great. 16

The legend was as follows: Tigranes (from Tigrish "arrow," the old Iranian name of the Babylonian Nabu), King of Armenia, was a friend of Cyrus the Great. His immediate neighbor on the east, Azdahak of Media, was in great fear of both these young rulers. One night in a dream, he saw himself in a strange land near a lofty ice-clad mountain (the Massis). A tall, fair-eyed, red-cheeked woman, clothed in purple and wrapped in an azure veil was sitting on the summit of the higher peak, caught with the pains of travail. Suddenly she gave birth to three full-grown sons, one of whom, bridling a lion, rode westward. The second sat on a zebra, and rode northward. But the third one, bridling a dragon, marched against Azdahak of Media and made an onslaught on the idols to which the old king (the dreamer himself) was offering sacrifice and incense. There ensued between the Armenian knight and Astyages a bloody fight with spears, which ended in the overthrow of Azdahak. In the morning, warned by his Magi of a grave and imminent danger from Tigranes, Aldahak decides to marry Tigranuhi, the sister of Tigranes, in order to use her as an instrument in the destruction of her brother. His plan succeeds up to the point of disclosing his intentions to Tigranuhi. Alarmed by these she immediately puts her brother on his guard. Thereupon the indomitable Tigranes brings about an encounter with Azdahak in which he plunges his triangular spear-head into the tyrant's bosom pulling out with it a part of his lungs. 17 Tigranuhi had already managed to come to her brother even before the battle. After this signal victory, Tigranes compels Azdahak's family to move to Armenia and settle around Massis. These are the children of the dragon, says the inveterate rationalizer, about whom the old songs tell fanciful stories, and Anush, the mother of dragons, is no one but the first queen of Azdahak. 18

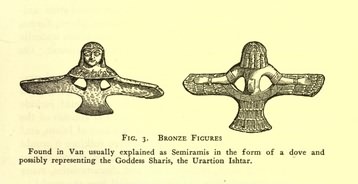

FIG. 3. BRONZE FIGURES. Found in Van usually explained as Semiramis in the form of a dove and possibly representing the Goddess Sharis, the Urartion Ishtar.

NOTES

1. Here, of course, the valuable tale of the epics has vanished before the Biblical conception of the spread of mankind, but a dim memory of the events that led to the separation of the Armenians from their mighty brethren of Thrace or Phrygia, as well as something of the story of the conquest of Urartu by the Armenians, seems to be reflected in the biblicised form of the legend.

2. Moses, i. 10, ii.

3. Alishan, p. 126.

4. Dr. Chapman calls my attention to the passages in Sayce's and Sandalgian's works on the Urartian inscriptions, where they find the name Huas or c Uas. Sandalgian also explains it as Hayk. (Inscriptions Cuneiformes Urartiques, 1900, p. 437.) See also the appendix on Vahagn in this work.

5. A. H. Sayce, The Cuneiform Inscriptions of Van, p. 719.

6. This is the prevailing view among modern scholars. The word that was current in this sense in historical times was azat (from yazatat), " venerable." Patrubani sees in Hayk the Sanskrit fana and the Vedic payn, "keepe "; Armen. hay-im, "I look."

7. Republic, x. 134.

8. Patrubani explains Armenus as Arya-Manah, " Aryan (noble? )- minded." The Vedic Aryaman seems to mean "friend," "comrade."

9. This is not impossible in itself as we find a host of Arabic words and even broken plurals in pre-Muhammedan Armenian.

10. Nychar is perhaps the Assyrian Nakru, "enemy" or a thinned-down and very corrupt echo of the name of Hanagiruka of Mata, mentioned in an inscription of Shamshi-Rammon of Assyria, 825-812 B.C. (Harper, Ass. and Bab. Liter., p. 48).

11. Moses, i. 15. See also additional note on Semiramis, Appendix

12. Republic. 134.

13. Pamphylians were dressed up like the Phrygians, but they were a mixed race.

14. See art. "Gilgamesh" in EBR al ; also F. Jeremiah's account of the myth in Chantepie de la Saussaye, Lehrbuch 3 , i. 33if. Frazer in GB 3 part iv, Adonis, Attis y and Osiris, ch. 5, gives an interesting account of kings, who, through self -cremation on a funeral pyre, sought to become deified. He tells also of a person who, having died, was brought back to life through the plant of life shown by a serpent (as in the well-known myth of Polyidus and Glaucus, cf. Hyginus, Fab. 136, and for Folk-tale parallels, J. Bolte and G. Polivka, Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- und Haus-Marchen der Bruder Grimm, Leipzig, 1913, i. 126 f.). Further, we learn through Herodotus (iv. 95.) that Zalmoxis, the Sabazios of the Getae in Thrace, taught about the life beyond the grave, and demonstrated his teaching by disappearing and appearing again.

15. Sayce, Cuneiform Inscriptions of Van y p. 566. We may also point to the verbal resemblance between Er-Ara and the Bavarian Er, which seems to have been either a title of Tiu = Dyaus, or the name of an ancient god corresponding to Tiu.

16. For the real Tigranes of this time we may refer the reader to Xenophon, Cyrofaedia, iii. i. Azdahak of Media is known to Greek authors as Astyages, the maternal grandfather of Cyrus the Great.

17. According to classical authors the historical Astyages was not killed by Tigranes, but dethroned and taken captive by Cyrus.

18. According to Herodotus (i. 74) the name of the first queen of Astyages was Aryenis. .Anush is a Persian word which may be interpreted as " pleasant." But it may also be a shortened form from anushiya, " devoted." This latter sense is supported by such compound names in Armenian as connect anush with names of gods, e.g. Haykanush, Hranush, Vartanush, etc.